Well, Mr. Scatter does, for one.

Sitting here at the Scatter International Clearing Desk this afternoon he ran across a press release from the Portland Art Museum, announcing an upcoming lecture by Iwona Blazwick, director of Whitechapel Gallery in London. The talk will be at 2 p.m. Sunday, April 18, in the museum’s Whitsell Auditorium, and it’s titled Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Institutions So Different, So Appealing?

The press release begins with this provocative quote from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti‘s 1909 Futurist Manifesto, denouncing museums as “cemeteries – absurd abattoirs of painters and sculptors ferociously slaughtering each other – cemeteries of crucified dreams, registries of aborted beginnings.”

The press release begins with this provocative quote from Filippo Tommaso Marinetti‘s 1909 Futurist Manifesto, denouncing museums as “cemeteries – absurd abattoirs of painters and sculptors ferociously slaughtering each other – cemeteries of crucified dreams, registries of aborted beginnings.”

Provocative, and dead wrong, which Mr. Scatter believes is precisely Ms. Blazwick’s point. The manifesto is a fire-breathing document, and a century later it still has the furious charm of a comic-book battle between a superhero and an archvillain. It’s filled with the sort of seductive fantasies that would turn a 17-year-old’s head ( “We want to glorify war – the only cure for the world – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of the anarchists, the beautiful ideas which kill, and contempt for woman” ) and led naturally, in all its adolescent streamlined illogic, to Mussolini and Italian Fascism.

Which is not to say that the existence of museums had a wisp of a deterring influence on Fascism or Communism or any other ism. Once humankind gets the Ism bug it’s almost impossible to get rid of it until it’s run its destructive course. Nor does it reduce the irony that the marbled walls of the world’s museums now hang with Futurist works, one more category of historical relic, testament to a movement that had its day of glory and then flamed out.

Which is not to say that the existence of museums had a wisp of a deterring influence on Fascism or Communism or any other ism. Once humankind gets the Ism bug it’s almost impossible to get rid of it until it’s run its destructive course. Nor does it reduce the irony that the marbled walls of the world’s museums now hang with Futurist works, one more category of historical relic, testament to a movement that had its day of glory and then flamed out.

But in a larger sense the world of museums is a line of defense against the fools. Wisdom and beauty, while infinitely debatable, are real, and when we lose or ignore them we lose or ignore not just some immaterial specter of the past but our very sense of who and where we are, and what we might become. It’s tough to throw bricks through the windows of the past once you realize that the past has shaped what you are — unless, that is, you are so self-loathing or recklessly thrill-seeking that you want to punish yourself.

Yes, museums can be intimidating. The better ones are working on that. But this is our story, friends. This is the repository of human creativity at its best. Mr. Scatter confesses to astonishment over the number of artists he has heard speaking impatiently or dismissively about museums and the objects that they hold, as if it were a badge of bravery and independence to create afresh with little knowledge of what has been created before. Why are our young artists not haunting the halls of the museums? Rarely — almost never — do you see someone set up with easel and paints in a Portland Art Museum gallery, copying the masters to learn their techniques, a sight that is common in European museums. Are our artists afraid that if they study their forebears they will have no ideas of their own? Do they have so little confidence, or are they so bull-headed? A museum is a despot only if you choose to be a slave. Mr. Scatter thinks of museums as places of intellectual and spiritual refreshment, places where we discover ideas that are greater than our own; ideas that sometimes in turn can spark ideas that are genuinely new. A little humility opens marvelous doors.

And it opens those doors to all of us, or at least to the great majority of us. Art that might have been made for the ruling class is now available to anyone who walks through those doors. It’s the same democracy as the democracy of the library: one of the great, true achievements of progress. Mr. Scatter notes with pleasure that the Whitechapel Gallery was founded in 1901 “to bring great art to the working class people of east London,” and that commitment to redistributing the cultural wealth ought to be at the core of every museum.

A museum is not a place to worship blindly. We argue with it, sometimes vociferously, because we all have a stake in it. Over the years museums change, partly because of that pressure: they evolve, innovate, reassess; sometimes they even undergo mini-revolutions. Still, it’s a good idea to keep a grip on the baby when you’re throwing out the bathwater. Mr. Scatter assumes that the process of keeping the tub fresh will be central to Iwona Blazwick’s lecture. Sounds invigorating — in a post-adolescent way.

*

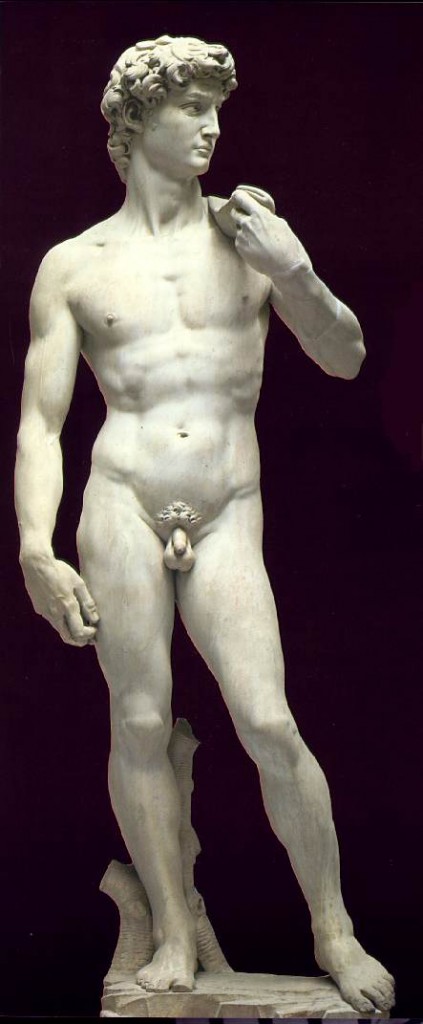

Coincidentally, a friend of Mr. Scatter in Santa Fe sent this link this afternoon to a story in The Guardian, which she’d been sent by her husband, who’s in Paris right now. Jonathan Jones’ column, titled Leonardo or Michelangelo: who is the greatest?, offers a terrific reappraisal of the two most famous works in Western art history, Michelangelo’s David and Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, digging below the contempt of familiarity to rediscover the sources of their greatness. In the process he revives the fascinating history of the rivalry between these two masters and what it meant. Far more, as it turns out, than the blustering dictums of the Futurist Manifesto.

You can find David and Mona Lisa, by the way, in museums. Sure, you’ve got to fight the crowds. But there they are. And not a reactionary cobweb in sight.

So one day last week I picked up my old copy of

So one day last week I picked up my old copy of