All critics are equal, but some are more equal than others. Or at least more powerful. Then again, the powerful aren’t always the best critics. Too used to getting their own way, or prone to tantrums when they don’t.

With apologies to the good pigs of Animal Farm, I bring this up because of this morning’s news — the latest bit in a decades-long accumulation, really — that former President Richard Nixon truly hated modern art, in whatever form he encountered it. How frustrating it must have been for him that he couldn’t stem its tide.

With apologies to the good pigs of Animal Farm, I bring this up because of this morning’s news — the latest bit in a decades-long accumulation, really — that former President Richard Nixon truly hated modern art, in whatever form he encountered it. How frustrating it must have been for him that he couldn’t stem its tide.

This morning’s report by Calvin Woodward of the Associated Press on the latest release of papers from the presidential files (280,000 pages from the Nixon Library, which is run by the National Archives) has plenty to say about politics and spying and matters of intense national import such as keeping tabs on Ted Kennedy’s love life.

It also reveals, once again, Nixon’s detestation for the modern art — “those little uglies” — that John Kennedy had embraced and helped make fashionable. Woodward reports:

Nixon despised the cultural influences of the Kennedys and their liberal circles.

He called the Lincoln Center in New York a “horrible monstrosity” that shows “how decadent the modern art and architecture have become,” and declared modern art in embassies “incredibly atrocious.”

“This is what the Kennedy-Shriver crowd believed in and they had every right to encourage this kind of stuff when they were in,” he wrote. “But I have no intention whatever of continuing to encourage it now. If this forces a show-down and even some resignations it’s all right with me.”

Nixon further calculated, Woodward reports, that stiffing the modern art crowd would be no big political problem: “(T)hose who are on the modern art and music kick are 95 percent against us anyway.”

Maybe so, although a lot of captains of industry — people who presumably would have had a good deal at stake in the decisions of the Nixon administration — have been ardent collectors and promoters of modern art and music. Certainly Nixon was entitled to his own views on art. and he was undoubtedly right that figures such as “that son of a bitch” Leonard Bernstein held him in at least equal contempt. (See this intriguing report from Caffeinated Politics about how Nixon ducked out of a performance of Bernstein’s Mass at the Kennedy Center, and, incidentally, knocked Stravinky’s Rite of Spring.)

It’s also true that modernism has often been targeted as an enemy by totalitarian regimes. Stalin had his campaign against “degenerate” art. Hitler, too. And the rise of statist xenophobia in contemporary Europe is often accompanied by support for nostalgic, kitschy art from the good old days of national purity. Modernism kicks the supports out from under the status quo, and no totalitarian regime can put up with that sort of thing.

In a way it’s no surprise that powerful people’s taste in art skews toward the conservative. That’s not necessarily a bad thing. When conservative taste is paired with a dedication to maintaining an understanding of history and cultural tradition it can be laudatory. (Isn’t that what museums do?) At times it can be even Quixotic. In England, Prince Charles’ campaign against modernism in architecture and in favor of maintaining traditional forms is routinely and witheringly castigated. He’s made out to be a blundering fool, and for all I know, he is. But I can’t help admiring his unwavering dedication to his cause.

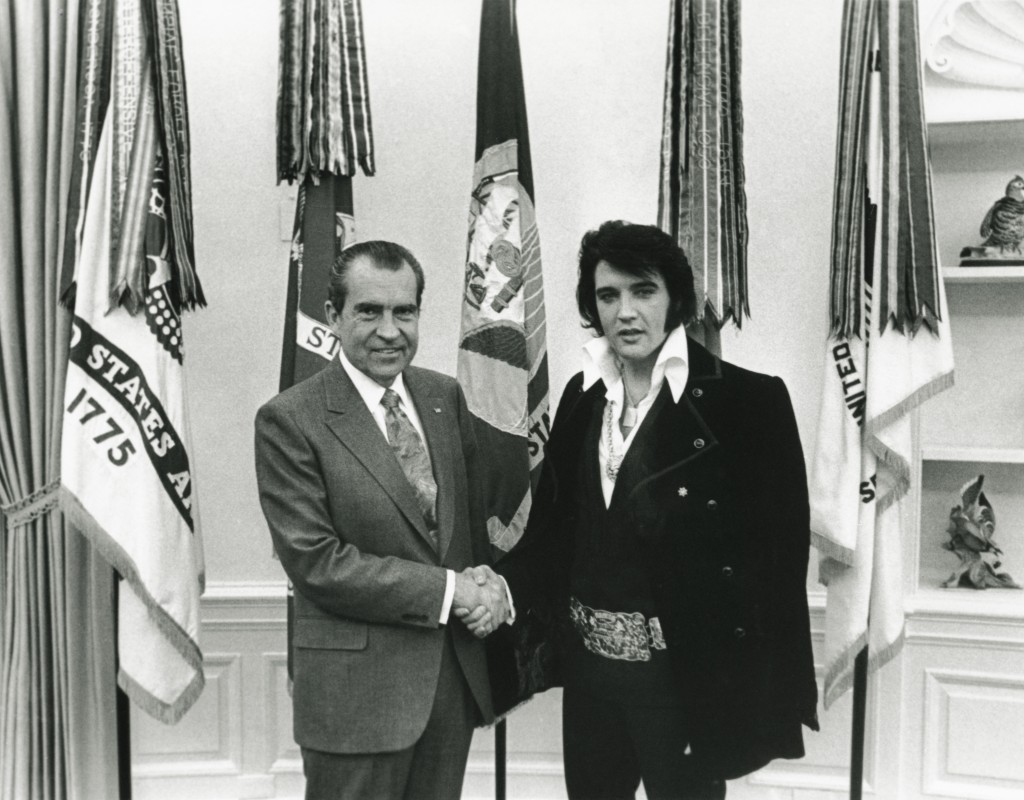

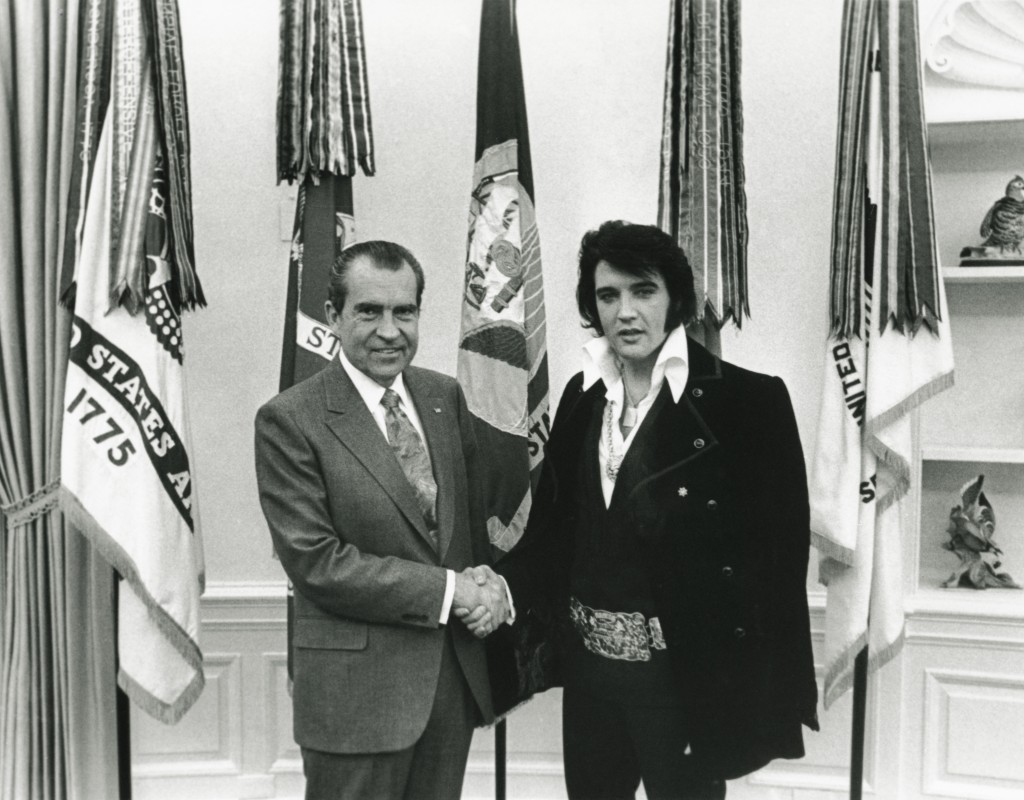

Still, Nixon missed out on some good art and music that conceivably could have encouraged a creative agility that might have kept him out of some of the mess he landed in. And if he didn’t actively promote art, he didn’t turn his distaste for modernism and modernists into a political campaign, either. (In fact, when he believed that being seen with a particular artist might be to his political advantage, he didn’t hesitate to pose.) It took another political generation for the “culture wars” to kick in and for art to be demonized as a tool of the effete disbelievers.

We’re still living with the effects of that cynicism, and maybe Nixon pointed the way for the apparatchiks of the culture-war crowd. But whatever his failures as a critic, Nixon kept his dislikes mostly private. This is one war that ain’t Nixon’s fault.

***************

PHOTOS, from top:

- The President and the King: Nixon poses with Elvis Presley, who was an enthusiastic patriot. Tough to imagine Nixon in blue suede shoes, but he knew a good photo op when he saw one. White House photo by Ollie Atkins, Dec. 21, 1970. Wikimedia Commons

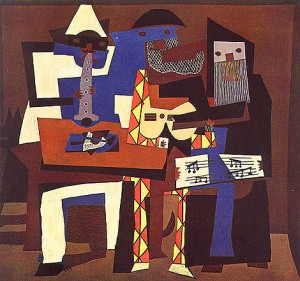

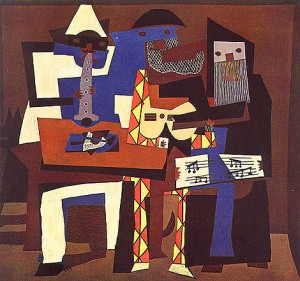

- Pablo Picasso, “Three Musicians,” 1921. Cubist, shmubist. Probably not a Nixon favorite.

Witnesses — those “I alone am escaped to tell you” chroniclers of catastrophe and adventure — are crucial figures in the world of the imagination. From the cautioning choruses of Greek tragedies to Melville’s wide-eyed sailor Ishmael, we’re used to the idea of the witness as a cornerstone of civilized life.

Witnesses — those “I alone am escaped to tell you” chroniclers of catastrophe and adventure — are crucial figures in the world of the imagination. From the cautioning choruses of Greek tragedies to Melville’s wide-eyed sailor Ishmael, we’re used to the idea of the witness as a cornerstone of civilized life. From the lofty perch of the present we stand as witnesses to time, looking back on history, rewriting it as we gain new reports from the trenches and rethink what we’ve already seen. We judge, revise, rejudge: In the courtroom of culture, the jury never rests.

From the lofty perch of the present we stand as witnesses to time, looking back on history, rewriting it as we gain new reports from the trenches and rethink what we’ve already seen. We judge, revise, rejudge: In the courtroom of culture, the jury never rests.

With apologies to the good pigs of Animal Farm, I bring this up because of this morning’s news — the latest bit in a decades-long accumulation, really — that former President Richard Nixon truly hated modern art, in whatever form he encountered it. How frustrating it must have been for him that he couldn’t stem its tide.

With apologies to the good pigs of Animal Farm, I bring this up because of this morning’s news — the latest bit in a decades-long accumulation, really — that former President Richard Nixon truly hated modern art, in whatever form he encountered it. How frustrating it must have been for him that he couldn’t stem its tide.