We have theorized (another way of saying “joked”) that Art Scatter is nothing but loose ends, a collection of them, maybe a little like “fringe” except not all the same length or so linear. But when I say, that I have some loose ends to tie up this week for you, I actually DO have something specific in mind.

We have theorized (another way of saying “joked”) that Art Scatter is nothing but loose ends, a collection of them, maybe a little like “fringe” except not all the same length or so linear. But when I say, that I have some loose ends to tie up this week for you, I actually DO have something specific in mind.

1. MoCA on the brink. Last week over at OregonLive I posted on the situation at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, which is dire — big deficits, crashing endowment, soaring expenses, oblivious staff and board of directors. Exactly how you let these things happen is a mystery: The endowment was shrinking even before the stock market crash, which has demolished everybody’s endowment, but now it’s down to $6 million or so for a museum that spends $21 million a year. For comparison’s sake, that’s less than one-fifth of the Portland Art Museum’s endowment for one of the world’s most important contemporary art museums. Which is crazy.

The New York Times’ Edward Wyatt and Jori Finkel summarized things on Thursday and added some new information. For example, the museum claims it produced an operating surplus last year and that its board is giving LOTS of money already. And Wyatt and Finkel detailed LA philanthropist/meddler (depending on your point of view) Eli Broad’s $30 million offer to MoCA: “In an interview this week, Mr. Broad offered details of his plan, saying he would give the museum $15 million in installments equal to however much the museum raised, plus $3 million a year for five years to pay for operations and exhibitions.” They also suggest that Broad wants new management at the museum and in that he is not alone.

Why do we care, exactly? Well, primarily because the curators at the museum have done an excellent job of sorting through the art of our time and making some provisional statements about it, about what’s important about it. The “apparatus” at the museum has generated important exhibitions and publications that have helped us think about art in new ways, to consider new artists and approaches. They have occasionally fallen prey to the special problems of the contemporary art museum — the politics created by for-profit galleries, for example, and the feeling that something vital and interesting and perhaps mysterious is being over-analyzed, smoothed over, commodified in front of our very eyes, sanitized by the white walls and tamed by the catalog. But this is just part of the ongoing balancing act they have to play. Mostly, LA MoCa has given us a useful description of recently created art, and I mean “useful” in a very robust way.

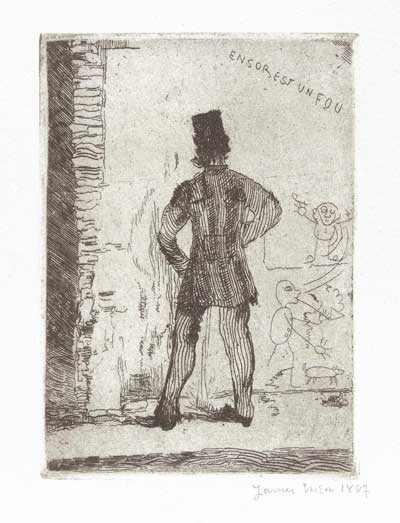

The James Ensor case. Another post I contributed to OregonLive reported (at characteristic length: beware!) on Louis Marchesano’s slide/lecture at PNCA on Belgian proto-modernist James Ensor, specifically the way Ensor’s prints inform (and are informed by) his most famous painting, Entry of Christ Into Brussels, 1889, which is owned by the Getty, where Marchesano works as curator of prints and drawings. Marchesano helped assemble a show of the painting and Ensor prints a couple of years ago for the museum.

The James Ensor case. Another post I contributed to OregonLive reported (at characteristic length: beware!) on Louis Marchesano’s slide/lecture at PNCA on Belgian proto-modernist James Ensor, specifically the way Ensor’s prints inform (and are informed by) his most famous painting, Entry of Christ Into Brussels, 1889, which is owned by the Getty, where Marchesano works as curator of prints and drawings. Marchesano helped assemble a show of the painting and Ensor prints a couple of years ago for the museum.

Marchesano came across as a slim, fashionably bespectacled and apparelled, smart guy, very interested in Ensor, even though his own area of expertise is Old Master prints. I think what struck me most about his presentation has to do with the previous item somehow: The idea that a painting that STILL seems pretty wild and wooly, absolutely of its time and place, reacting to social and political and aesthetic conditions on the ground in Belgium in 1888, finds itself ensconced in a museum that is remote from that time and place, and yes, sanitized of its most bacterial bits. I say that even though Marchesano himself actually delighted in those same infectious bits — specifically the scatalogical bits.

Entry of Christ Into Brussels, 1889 still seems part of our time, for reasons I tried to explain in the original post, and contemplating it in the serenity of the Getty seems somehow strange. It has been turned into a precious object instead of a bristling conveyor of cultural information, cultural aspirations, personal history and neurosis… you get the idea. And that is the problem of the contemporary art museum, too, especially as they have become glittering palaces that suggest their embrace by power. Entry of Christ Into Brussels, 1889 positively hates that power. I can only imagine what the Ensor of 1888 would have said about Eli Broad.