If someone asked me the impossible question, “What have been the most important works of art produced in Portland in the past 15 years,” I’d probably stall for time and then include Joe Sacco’s Palestine and Craig Thompson’s Blankets on my list. Most of that has to do with the quality and the startling originality of both books. But some would be because their art form, the “graphic novel,” is in its infancy and good work therefore has more influence on it.

At this point, the standing of the graphic novel as an art form needs no defense. It might need some definition, though — some of the best of what we call “graphic novels” aren’t really novels at all, by which I mean simply that they aren’t intentional fictions. They are journalism or memoir or a hybrid of the two. Sacco’s Palestine is a case in point and so is Thompson’s Blankets, one an account of two-and-a-half months traveling in the Middle East and the other a memoir of growing up in an evangelical Christian family.

At this point, the standing of the graphic novel as an art form needs no defense. It might need some definition, though — some of the best of what we call “graphic novels” aren’t really novels at all, by which I mean simply that they aren’t intentional fictions. They are journalism or memoir or a hybrid of the two. Sacco’s Palestine is a case in point and so is Thompson’s Blankets, one an account of two-and-a-half months traveling in the Middle East and the other a memoir of growing up in an evangelical Christian family.

So, with the purpose of taking the novel out of “graphic novel” and replacing it with… something else, I’m proposing a three-book, four-part excursion into a particular combination of text and drawing. And this introduction is Part One. Not to worry: The parts will be short.

Neither Palestine nor Blankets is on the docket. They’ve been described a LOT (even I have written about Palestine before). But both Sacco and Thompson are. French-Canadian cartoonist/graphic memoirist Guy Delisle also figures. In the three books we’ll consider, these artists share a few things in common:

1) They give a “true” account of what they witnessed and felt. I don’t mean true in the sense that a novel can be “true” to life. I mean that they explicitly hope to convey what they’ve seen and/or experienced.

2) Their accounts are in first person. We know exactly where they stand in the narrative and in relationship to the people they are representing in text or pictures. Often we can place them literally: Just outside the frame of the drawing, near enough to make out the details we see. Other times, they have drawn themselves into the frames.

3) Their own shifting states of mind figure prominently: They tell us how the way they are feeling or thinking might affect the narratives we are reading/viewing.

4) Although their drawing aims and intensity levels may differ, their visual images are at least as important as the words. In fact, we might be inclined to contest some of the text, knowing what we know about the limits of reporting and interviewing, but the drawings of all three are immediately convincing, despite their different styles. The drawing don’t just convey information, either, they create a felt world for the reader/viewer.

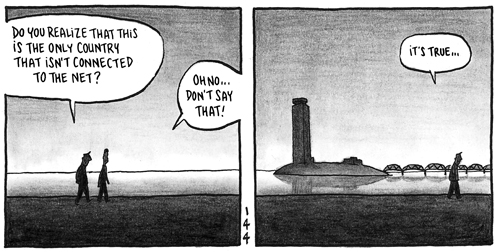

As we look at the work — Thompson’s Carnet de Voyage (2004, Top Shelf Productions), Delisle’s Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea (2003, Drawn and Quarterly Books) and Sacco’s War’s End: Profiles From Bosnia 1995-96 (2005, Drawn and Quarterly Books) — we’ll keep an eye out for how they do “journalism” and memoir, what problems their methods generate, what in the end makes this form and their individual descriptions of life important. The observation that this sort of graphic non-fiction shouldn’t be called a “graphic novel,” isn’t new, of course (see Douglas Wolk’s Reading Comics, p. 62, for example). But maybe we’ll figure out what to call them, once we look at a few in detail.

Except that maybe we’ve read Blankets, and we’re pretty sure that Craig is not going to be able to give himself over to that sort of thing. And in fact, Craig is unhappy for a lot of Carnet. He counts the ways: he’s homesick, he misses his ex-girlfriend profoundly, she’s quite ill, he’s lonely, everything reminds him of her, he’s lonely, his hand hurts from so much drawing. Did we mention he’s lonely? His internal struggles spill out into the frames and pages of his notebook, enveloping them in fog of gloom. Morocco, near the beginning of the trip, is especially difficult, primarily because he doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t understand the culture very well and plunges into the worst melancholy of the trip.

Except that maybe we’ve read Blankets, and we’re pretty sure that Craig is not going to be able to give himself over to that sort of thing. And in fact, Craig is unhappy for a lot of Carnet. He counts the ways: he’s homesick, he misses his ex-girlfriend profoundly, she’s quite ill, he’s lonely, everything reminds him of her, he’s lonely, his hand hurts from so much drawing. Did we mention he’s lonely? His internal struggles spill out into the frames and pages of his notebook, enveloping them in fog of gloom. Morocco, near the beginning of the trip, is especially difficult, primarily because he doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t understand the culture very well and plunges into the worst melancholy of the trip.