For Part Two on Craig Thompson, click here. The introduction is here.

Like Carnet de Voyage, though less explicitly, Pyongyang: a Journey in North Korea is a journal of a trip. In this case it’s Guy Delisle’s business trip to North Korea. Delisle, a French Canadian, worked for a French animation company, which farmed out big chunks of the actual animation to North Korea (Delisle says that Eastern European studios also get lots of this sort of work). Basically, the North Koreans take their cue from the the “key” drawings in a movement sequence and fill in the drawings between them. Delisle supervised their work.

But animation “experiences,” though informative (think about the whale rendering passages in Moby Dick, except shorter), don’t occupy many of the frames of Pyongyang. Instead, Delisle records the life he finds in North Korea. There is one very great difficulty to this: He must be accompanied everywhere he goes by a guide and translator. And he must stay in an almost empty hotel for foreigners, which is cut off from the rest of the city. So the book takes us on a series of excursions, some more impromptu than others, as Delisle attempts to get closer to the “real” Korea than the government wants him to get. If anyone has a complaint about loneliness, it’s Delisle, but he rarely mentions it. Instead, he works on his guides, trying to trick them into an admission of some kind or get them to take him somewhere off-limits. They seem pretty tolerant, even friendly in a distant sort of way, but they are NOT going to fall for Delisle’s tricks.

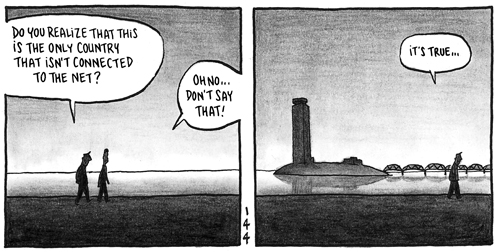

Given this tiny range of investigation, what do we learn? Quite a bit, actually. What immediately becomes apparent is the emptiness. Unlike the marketplaces in Morocco, teeming with beggars and grifters, Pyongyang seems abandoned in Delisle’s frames, only a skeleton crew left to mind it. The huge monuments to Kim Il-sung or Kim Jong-il are solitary, like Sphinxes in the desert. The streets have few cars, fewer pedestrians. Presumably there are markets, but we don’t visit them, so maybe not. Even the countryside, when we get there, seems de-populated. One of the primary affects of coercion and control at the North Korean level — human activity stops. And although his drawings are far less detailed than Thompson’s, Delisle recreates the static, deep-freeze environment, weird and exotic in its own way as Marrakesh.

Given this tiny range of investigation, what do we learn? Quite a bit, actually. What immediately becomes apparent is the emptiness. Unlike the marketplaces in Morocco, teeming with beggars and grifters, Pyongyang seems abandoned in Delisle’s frames, only a skeleton crew left to mind it. The huge monuments to Kim Il-sung or Kim Jong-il are solitary, like Sphinxes in the desert. The streets have few cars, fewer pedestrians. Presumably there are markets, but we don’t visit them, so maybe not. Even the countryside, when we get there, seems de-populated. One of the primary affects of coercion and control at the North Korean level — human activity stops. And although his drawings are far less detailed than Thompson’s, Delisle recreates the static, deep-freeze environment, weird and exotic in its own way as Marrakesh.

Stasis is an odd “topic” but it does make incidental events, like drinking too much with one’s guide and translator for example, seem dramatic. Melon at dinner? Time to celebrate… and then conclude that foreign delegations must be in the city. But “nothing” is going to happen. There’s no happy ending. Delisle puts in his two months. He packs up. He leaves. North Korea stays as he found it, though he HAS left a copy of 1984 with one of the translators, a bottle of Hennessy VSOP for his guide and some paper airplanes he’s floated from his hotel room to the city below. But Delisle is skilled enough to pull you along anyway, the inquisitive mind set loose on a place that actively resists providing answers.

How to characterize it… a memoir, yes, but not as personal as Craig Thompson’s Carnet. We learn nothing about Delisle’s sex life, either, or his thinking about much of anything except for North Korea. But it’s still a personal account: What I saw in North Korea, with the emphasis on the I, even though we suspect that the experience of any foreigner is going to be similar if not identical. And as blank as Delisle himself remains, like North Korea, he reveals something of himself. So a personal report, yes, one that acknowledges its limitations, in fact one that turns out to be ABOUT its limitations.

And if were going to label it, perhaps “graphic travel memoir” or “travel comics”? Something like that. In Part Four, we consider the ne plus ultra of comics journalism, Joe Sacco.