For the intro to this series click here. Do the same for Part two and Partthree.

Both Craig Thompson (even in the looser diary format of Carnet de Voyage) and Guy Delisle follow comic book conventions. In Thompson’s work they show up in the idealized women, for example, the relative inexpressiveness of the faces and in the representation of himself as a Woody Allen kind of character usually underdrawn compared to the rest of the characters. Delisle’s Pyongyang reads even more like a comic — lots of frames per page, action (what there is!) moving along linearly, and his own self-depiction is VERY cartoony: none of the other characters is so unnaturalistic.

Sacco lives in a different world — War’s End: Profiles from Bosnia 1995-96 wants to demolish the acceptable boundaries of comics, the affect of most Sacco books. The subject matter is grimmer. The drawings act as though they want to spill off the page. Words can fill huge chunks of space. (There are moments in Carnet that resemble Sacco’s work: Thompson has cited Sacco as an influence.) I like the subversion and the obsession with getting it right: We interpret it immediately as “seriousness of purpose,” and I accept it as a reasonable account of what happened, especially the events that Sacco witnessed directly.

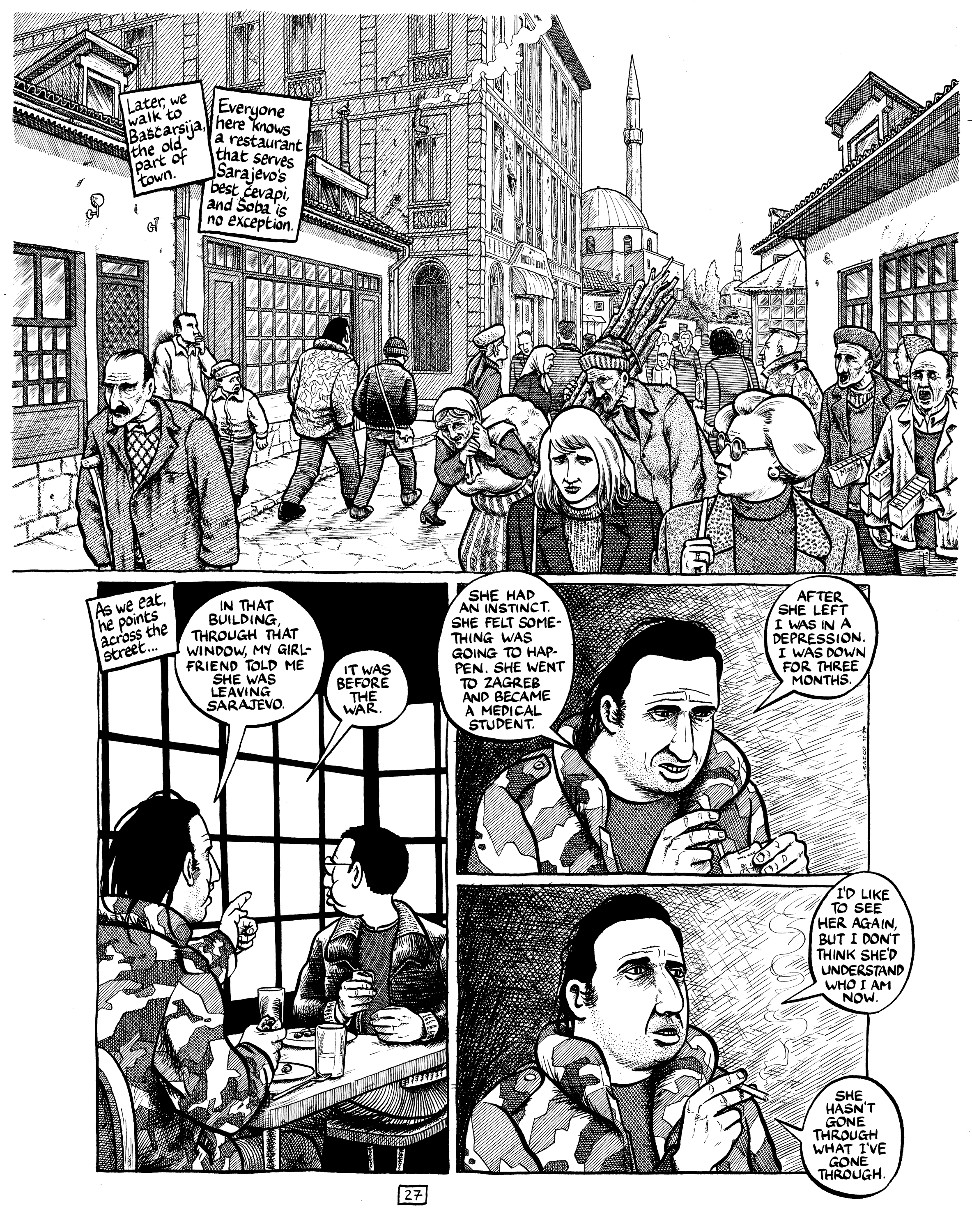

This isn’t Sacco’s best-known work on the war over the independence of Bosnia — that would be Safe Area Gorazde: The War in Eastern Bosnia 1992-95 (2000). War’s End was released in a hardback version in 2005, collecting two shorter pieces that appeared in the 1990s, Soba! and Christmas with Karadzic. Soba! is a profile of a chunky rocker/artist/soldier in the Bosnian Army. Much of the story is in the form of Soba’s recollections of fighting at the front (he dealt with mines, laying them and deactivating them). And then as peace approached, Sacco watched Soba attempt to make the transition from war to peace.

I have my doubts about Soba as a reliable narrator of his war experiences. Maybe Sacco tested his stories in various ways (talking to his friends, for example), but he doesn’t tell us that. We are intended to accept intense images of war as fact, when we know they are reported recreations that couldn’t be as dense with data as Sacco’s drawings are. The frame of Soba clutching a tree root as his hillside position is shelled , while men around him are dying and the sky is swirled and illuminated by the bombardment, is incredibly powerful, but was Soba’s automatic rifle leaning just so against the root? It’s hard to believe that Sacco KNOWS that. On the other hand Soba’s account deserves a hearing, whether we think it’s absolutely factual or not, and it’s not outlandish by any means.

Once we get to Soba in peacetime, though, and Sacco himself is on hand to observe and record, that’s a different story. It’s utterly believable, down to the expressions on Soba’s face. Sacco himself appears in these frames, not a flattering picture, mainly just listening and watching, but his presence gets us back on solid reporting ground. And it’s actually more interesting than the war frames: Soba struggles to come to grips with the absence of war — how does he pick up his life, does he stay in Sarajevo or leave for Italy, can he overcome his jitters and his bravado, has he been rendered too crude for “normal” life? Sacco likes him, it’s apparent, BUT he can’t help but depict him at his worst (often in pursuit of women). It’s a brilliant portrait.

Christmas With Karadzic is about two journalists Sacco is hanging with and their attempt to interview the notorious head of the Bosnian Serbs, Radovan Karadzic, later indicted for war crimes. What does Sacco report: The cynicism of the reporters, their shaky representation of reality (trying to get gunfire on tape when it’s quiet, for example) and ultimately their success at getting a few minutes with Karadzic at a Christmas church service. But it’s still a sharp, speedy drive through dangerous territory. The surprise? That Sacco himself can’t work up any outrage at Karadzic, a man who represents atrocities that he loathes. Sacco’s sensibility has changed; not his politics, but his capacity to respond. The writer testifies to the transformative nature of what he has witnessed, and it spills over to the other characters, who, we reason, have adapted to the war to a similar degree, personalities evolving, deteriorating, defenses erected, hardening, coarsening, like Soba. Sacco takes us to the extremities of this bitter little Balkan conflict — the 10,000 dead in Sarajevo alone, the life and lives blown apart — for both the dead and the living.

Sacco’s drawing is both expressionistic (look at the dogs on cover of War’s End) and unusually detailed, and he gets the full impact of both. We get the feeling from his dark, kinetic images and the testimony to his accuracy from the details. It’s difficult for us to really examine, to read, to interpret the drawings; we just don’t want to go there with Sacco. If Soba is a sympathetic character, if Sacco himself becomes numb to Karadzic, falls into the aggressive cynicism of the journalists around him, then we should consider ourselves warned.

Journalism can’t do more than this.

The only problem with Sacco’s graphic journalism is how time consuming it is; it becomes graphic history as he labors at the drawing table. But that’s a fine category, too. And when we consider Sacco, Thompson and Delisle together, we embrace their variety, the way they span possible categories, the way they define themselves as they go along. No, “graphic novel” does not contain them; they argue for a much larger set of names. Oh, and they win that argument.