By Martha Ullman West

How little we know them, these artists who gladden our hearts and feed our souls, I thought a week ago. I was sitting, sadly, at Carolyn Holzman’s memorial at Holman’s Funeral Service, listening with an SRO crowd to heartbroken yet frequently funny tributes by family, friends and colleagues.

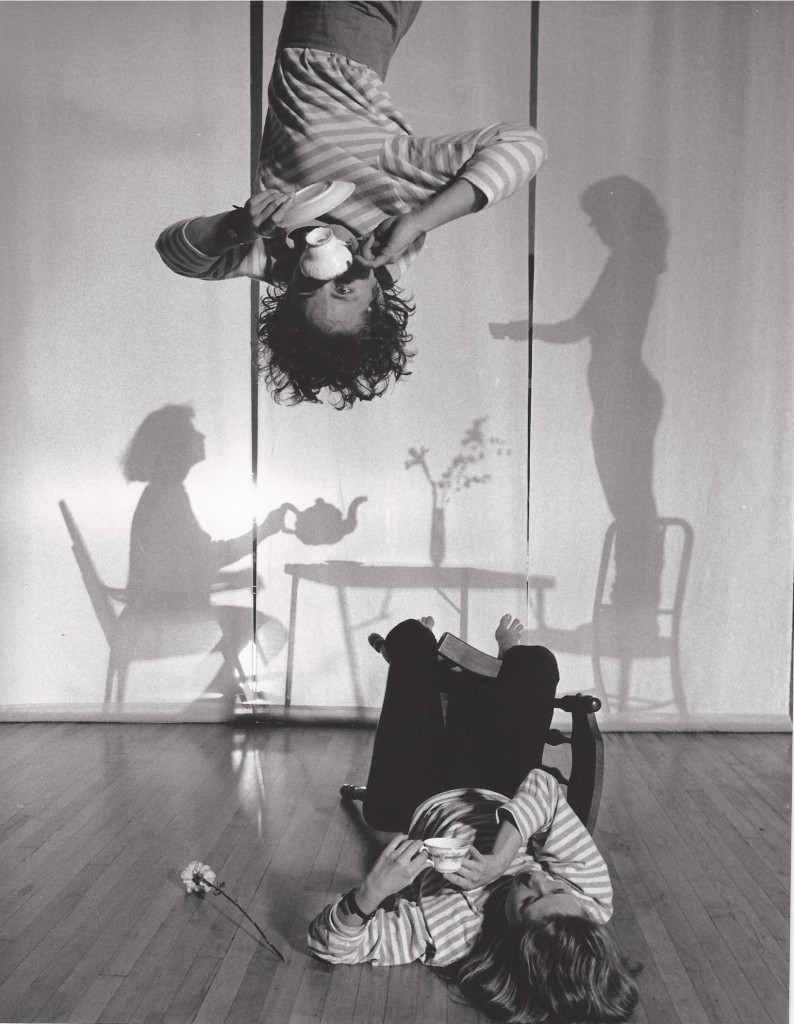

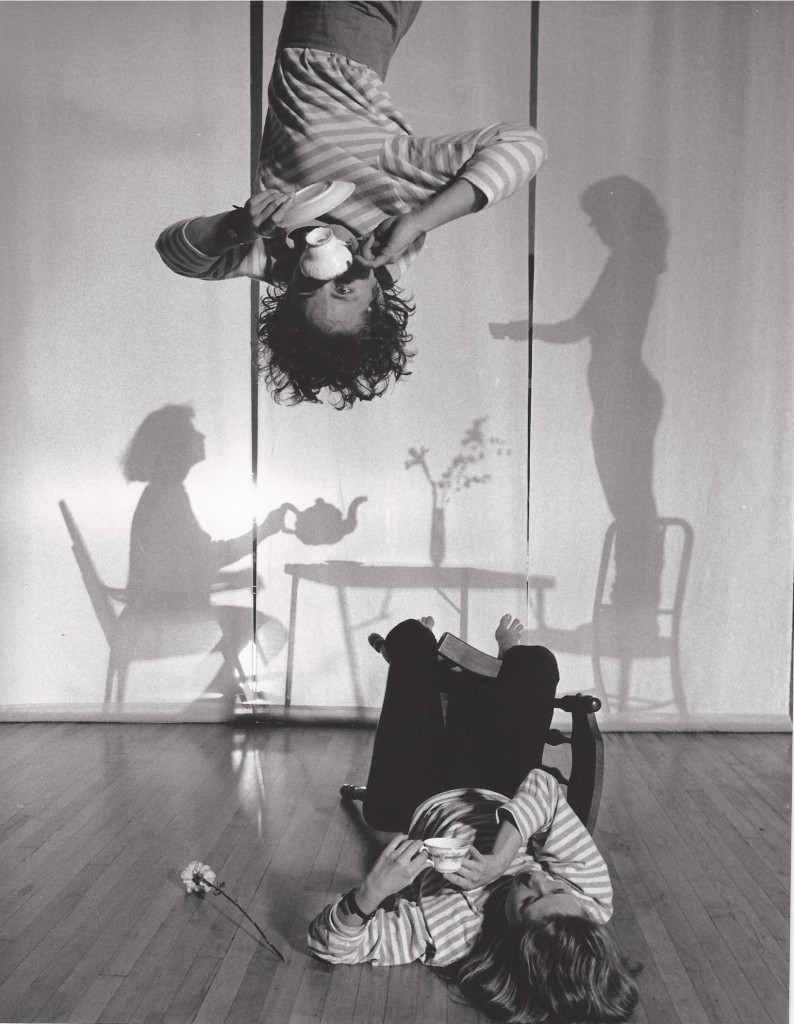

What I do know about Holzman, who died of a heart attack at 55 — too soon, much too soon — on August 5th, was that thirty years ago she could send me into paroxysms of laughter as a member of Do Jump! Extremely Physical Movement Theatre. I don’t need the photos posted here to remind me of her, hanging from the ceiling of the Echo Theatre, a maniacally gormless expression on her face, in that mad tea party Robin Lane called Out of Context, in simultaneous defiance of gravity and gravitas.

What I do know about Holzman, who died of a heart attack at 55 — too soon, much too soon — on August 5th, was that thirty years ago she could send me into paroxysms of laughter as a member of Do Jump! Extremely Physical Movement Theatre. I don’t need the photos posted here to remind me of her, hanging from the ceiling of the Echo Theatre, a maniacally gormless expression on her face, in that mad tea party Robin Lane called Out of Context, in simultaneous defiance of gravity and gravitas.

Or in Power Lunch — made long before women named the glass ceiling that would keep them from rising to the top — everything tailored about her except her hair (her hair was inevitably part of performances, it seems to me), toes in wrinkled pantyhose pointed at the floor, seeming to be rising straight to the top, but warily.

In short, I knew her as a member of Do Jump! in its early days when Lane took serious issues and used them to make fun of human foibles, aided and abetted by Holzman as well as Janesa Kruze and Holzman’s dear, close friend Laurene Reiner, who led the tributes with what she called “a little speech.”

Reiner thanked us for coming: Holzman’s students from Portland State, where she had been an adjunct professor in the theater department since the mid-Seventies; members of the dance and theater community (Josie Moseley was there, as was Susan Banyas); friends and colleagues from her days with Do Jump!, Robin Lane, Poppy Pos, with whom she often collaborated on costuming; many people I couldn’t identify who turned out to be her family; and her husband, Chris Cooksey’s, family, several of whom also spoke. I had no idea she had married her Reed College sweetheart, in an old-fashioned marriage of mutual support and mutual devotion. Or that she had enormous expertise in rehabilitating old houses, or, if it comes to that, that she loved Jello because she thought it was beautiful.

But I found myself nodding in agreement as Steiner spoke of her as a practitioner of physical comedy, first in Portland Mime Theater, then in Do Jump: “[She] was one of those fully engaged, committed performers, always aware of everything that was going on during a performance on the stage.” And Steiner recalled a moment in Lane’s Never My Head, a complicated piece in which one set of performers stands on a long, raised platform, and another set is placed below with yards of cloth stretched in the middle so that all the audience sees is the heads and feet of the performers.

“Carolyn loved the intricacy and the precision needed to pull the piece off properly,” Steiner said. “Because you had to keep the head lined up with the feet just right. She was tireless in her pursuit of just the right balance of physical perfection and performance élan. She would be standing above me on the platform doing her head thing and I would be below doing the feet thing, and all of a sudden I would feel this small but somewhat vise-like grip on my shoulder as she maneuvered me into better alignment. All the while she would be committed totally to the acting needed to complete the illusion. … I was lucky enough to be able say I was once the feet of Carolyn Holzman.”

Continue reading A tribute to Carolyn Holzman →

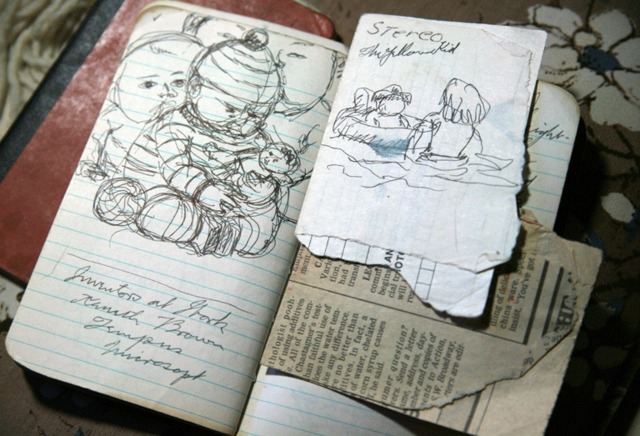

Tom Prochaska, So Much To Do, Froelick Gallery

Tom Prochaska, So Much To Do, Froelick Gallery

Even in local and regional scenes, people get lost, especially after they’ve died: Out of sight, out of mind. In a way

Even in local and regional scenes, people get lost, especially after they’ve died: Out of sight, out of mind. In a way  The new baby arrived the other day, and it’s a whopper: 12.2 inches long, 10.3 inches across, almost 2 inches thick and 8.5 pounds. It came after a labor so long you don’t want to contemplate it, but when it finally arrived it came out handsome and beautifully illustrated.

The new baby arrived the other day, and it’s a whopper: 12.2 inches long, 10.3 inches across, almost 2 inches thick and 8.5 pounds. It came after a labor so long you don’t want to contemplate it, but when it finally arrived it came out handsome and beautifully illustrated.

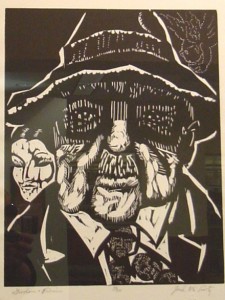

Pacific Northwest College of Art

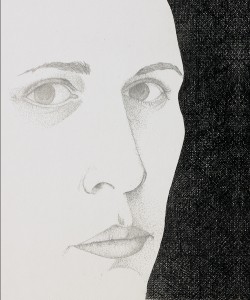

Pacific Northwest College of Art I never really knew Jack, although I talked with him several times. In the 1970s and ’80s I used to frequent the old Image Gallery that he and his wife Barbara ran downtown, a pioneer space that included Inuit and Mexican and other “folk” art in addition to McLarty’s own brand of homegrown modernism — pretty much no one of note was as intensely a Portland artist as he was. I reviewed a couple of his shows, briefly, and always enjoyed the long chatty letters that Barbara sent out, blends of professional marketing and family updates. I sometimes thought of McLarty as a sort of flip-side

I never really knew Jack, although I talked with him several times. In the 1970s and ’80s I used to frequent the old Image Gallery that he and his wife Barbara ran downtown, a pioneer space that included Inuit and Mexican and other “folk” art in addition to McLarty’s own brand of homegrown modernism — pretty much no one of note was as intensely a Portland artist as he was. I reviewed a couple of his shows, briefly, and always enjoyed the long chatty letters that Barbara sent out, blends of professional marketing and family updates. I sometimes thought of McLarty as a sort of flip-side

What I do know about Holzman, who died of a heart attack at 55 — too soon, much too soon — on August 5th, was that thirty years ago she could send me into paroxysms of laughter as a member of Do Jump! Extremely Physical Movement Theatre. I don’t need the photos posted here to remind me of her, hanging from the ceiling of the Echo Theatre, a maniacally gormless expression on her face, in that mad tea party Robin Lane called Out of Context, in simultaneous defiance of gravity and gravitas.

What I do know about Holzman, who died of a heart attack at 55 — too soon, much too soon — on August 5th, was that thirty years ago she could send me into paroxysms of laughter as a member of Do Jump! Extremely Physical Movement Theatre. I don’t need the photos posted here to remind me of her, hanging from the ceiling of the Echo Theatre, a maniacally gormless expression on her face, in that mad tea party Robin Lane called Out of Context, in simultaneous defiance of gravity and gravitas. David Cooper/OSF

David Cooper/OSF Judith H. Dobrzynski passes along

Judith H. Dobrzynski passes along