“My breakfast over, I paid a visit to Professor Jameson and proposed to him to give an account of the habits of the Turkey Buzzard instead of the Wild Turkey. He appeared anxious to have either.”

-John James Audubon in his London journal (mid 1820s)

I finished the last book I carried with me on this trip to the Midwest and with nothing else to occupy my mind I scatter-shot the internet. (Nothing in the way I swim or compute could ever be mistaken for “surfing.”) Hereâ’s what I found in 30 minutes, give or take.

Who would have thought? Google “smelly boys” and in the first dozen entries you will find adverts for scents and refrigerator magnets, videos of boys smelling their socks, and an article about the protest over smelly boy products such as tees and magnets, etc., as demeaning to boys. “Harmless fun or a fashion faux pas?”

Who would have thought? Google “smelly boys” and in the first dozen entries you will find adverts for scents and refrigerator magnets, videos of boys smelling their socks, and an article about the protest over smelly boy products such as tees and magnets, etc., as demeaning to boys. “Harmless fun or a fashion faux pas?”

Here’s a site new to me, The Art & Crime Gazette, which explores the intersection between art and crime, featuring a quotation from the 2003 book, Crimes of Art + Terror, by Frank Lentricchia and Jody McAuliffe, professors at Duke University: “There is a small dark place in Western Civilization where great art stands side-by-side with terrorists and petty felons.” The book, reviewed here last year, argues at its most extreme that the impulse to create art and the impulse to commit violence “lie perilously close to each other.” L + M compare “literary explosives” and “actual explosives,” equate “imaginative acts” to “bloody deeds.” The Gazette is more balanced, and is very interesting. In the blog section they note a Barry Johnson Art Scatter post about bronze statues stolen and sold as scrap metal. Check out the Gazette and see what you think.

Conservative and liberal are meaningless terms in American thought. That limp mind on the Right, Rush Limbaugh, apparently claims that President Obama is doing such a good job of destroying the country that: “If al-Qaeda wants to demolish the America we know and love, they better hurry, because Obama is beating them to it.” The America he loves has no substance. He has a thought and it must be Good. Confidence of opinion based on total absence of fact. It reminds me of Ted Hughes’ poems about Crow, especially “Crow’s Theology”:

Crow realized God loved him-

Otherwise, he would have dropped dead.

So that was proved.Crow reclined, marvelling, on his heart-beat.

And he realized that God spoke Crow-

Just existing was His revelation.But what Loved the stones and spoke stone?

They seemed to exist too.And what spoke that strange silence

After his clamour of caws faded?And what loved the shot-pellets

That dribbled from those strung-up mummifying crows?

What spoke the silence of lead?Crow realized there were two Gods-

One of them much bigger than the other

Loving his enemies

And having all the weapons.

dateline willow lake – Kum ‘N Go is gone, replaced (in name sign only) by Super X. In my South Dakota hometown the once “Ye Olde … Whatever†signs have been replaced by vintage-script “Whatever . . . Shoppe†ones. And I forget how delightful it is to name the surrounding towns: Letcher, Loomis, Woonsocket, Ree Heights, Yale, Carthage, Carpenter and Iroquois, and the still barely 300+ Willow Lake, where I spent most of my first fourteen years, and where today I visit my Aunts Gloria and Rose, my only remaining relatives of my parents’ generation, who live a block apart, or, almost across town from each other.

dateline willow lake – Kum ‘N Go is gone, replaced (in name sign only) by Super X. In my South Dakota hometown the once “Ye Olde … Whatever†signs have been replaced by vintage-script “Whatever . . . Shoppe†ones. And I forget how delightful it is to name the surrounding towns: Letcher, Loomis, Woonsocket, Ree Heights, Yale, Carthage, Carpenter and Iroquois, and the still barely 300+ Willow Lake, where I spent most of my first fourteen years, and where today I visit my Aunts Gloria and Rose, my only remaining relatives of my parents’ generation, who live a block apart, or, almost across town from each other. A website away, I find that POET, LLC has spent twenty years “defining the art of biorefining,†that is, the production of ethanol from corn. POET began as a family farm operation in Wanamingo, Minnesota, in 1983, turned commercial operation in Scotland, South Dakota in 1986, and now has some two dozen plants in seven states throughout the Midwest. How have I missed this?

A website away, I find that POET, LLC has spent twenty years “defining the art of biorefining,†that is, the production of ethanol from corn. POET began as a family farm operation in Wanamingo, Minnesota, in 1983, turned commercial operation in Scotland, South Dakota in 1986, and now has some two dozen plants in seven states throughout the Midwest. How have I missed this?  Books come in all shapes and sizes and perform all sorts of functions, in addition to acting as containment vessel for reading “matter.†And almost anything can function as bathroom reading. Where else memorize your credit card numbers? Now, it turns out, almost everything is worth the paper it’s printed on.

Books come in all shapes and sizes and perform all sorts of functions, in addition to acting as containment vessel for reading “matter.†And almost anything can function as bathroom reading. Where else memorize your credit card numbers? Now, it turns out, almost everything is worth the paper it’s printed on.

Painting is reading is gardening. Weeds everywhere.

Painting is reading is gardening. Weeds everywhere.

As anthologies go, the monstrous Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: The University of California Book of Romantic and Postromantic Poetry (2009), edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey Robinson, is a Hummer pretending to be a hybrid. Combined with its sturdy predecessors, Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern and Postmodern Poetry, Volume One: From Fin-de-Siecle to Negritude (1996), and Volume Two: From Postwar to Millennium (1998), edited by Rothenberg and Pierre Joris, with 2600 combined pages, they are a fully-loaded triple trailer.

As anthologies go, the monstrous Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: The University of California Book of Romantic and Postromantic Poetry (2009), edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey Robinson, is a Hummer pretending to be a hybrid. Combined with its sturdy predecessors, Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern and Postmodern Poetry, Volume One: From Fin-de-Siecle to Negritude (1996), and Volume Two: From Postwar to Millennium (1998), edited by Rothenberg and Pierre Joris, with 2600 combined pages, they are a fully-loaded triple trailer.

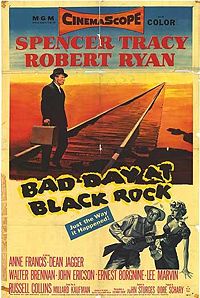

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. There are two plots, it is said: Someone Goes On A Trip and Stranger Comes To Town. That’s one plot, actually, with two points of view. Stranger must go on trip from some other town in order to come to ours.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. There are two plots, it is said: Someone Goes On A Trip and Stranger Comes To Town. That’s one plot, actually, with two points of view. Stranger must go on trip from some other town in order to come to ours. 1972, it turns out, was the year

1972, it turns out, was the year  Every Monday, new music lightens our dreary drive to Eugene and back. New releases come Tuesday so there’s a week’s delay and anticipation that figures into the mix, too. Yesterday it was “Sweet Thing,†the fourth song on Van Morrison’s new Astral Weeks Live at the Hollywood Bowl, before he was clearly mumbling – clearly mumbling, words as sounds tumbling and rolling out of his chest and throat — and we knew it was going to be a great drive. Astral Weeks (1968) has tracked this Scatter’s nearly forty year marriage and yesterday as the music washed over us, in scat-time to occasional shower, we were driving South Dakota back roads, not down I-5 and back. We didn’t even get to Keith Jarrett’s new Yesterday, which will now be next Monday or later.

Every Monday, new music lightens our dreary drive to Eugene and back. New releases come Tuesday so there’s a week’s delay and anticipation that figures into the mix, too. Yesterday it was “Sweet Thing,†the fourth song on Van Morrison’s new Astral Weeks Live at the Hollywood Bowl, before he was clearly mumbling – clearly mumbling, words as sounds tumbling and rolling out of his chest and throat — and we knew it was going to be a great drive. Astral Weeks (1968) has tracked this Scatter’s nearly forty year marriage and yesterday as the music washed over us, in scat-time to occasional shower, we were driving South Dakota back roads, not down I-5 and back. We didn’t even get to Keith Jarrett’s new Yesterday, which will now be next Monday or later.