Move over, blogsters. Clear the counters. It’s pickle time!

I had planned to tear down a fence this week, in part to keep the Large Smelly Boys busy because it’s the one week all summer when THEY’RE BOTH HOME. But then I realized it was the only few days I’d be in town during pickle season.

So, please, don’t bother to call. We’re too busy with mustard seeds, canning salt and – oh yeah – cukes!

We make bread and butters, dills and sweets. Other times we make jam, apple chutney, pesto and mustard. So you might think we’re the Scatter Family, but really we’re the Condiment Family.

Why pickles? Well, we like to eat ’em, we like to make ’em, we like to give ’em away.

But there’s a deeper level, and it’s a sweet and sad little story. I first “published” it somewhere else on the internets, so forgive me if you’ve read it before. It’s slightly adapted for this audience. I originally wrote it as part of a series of stories about the author Henry James.

Why pickles make the perfect present

OR

Changing the literary landscape, one jar of pickles at a time

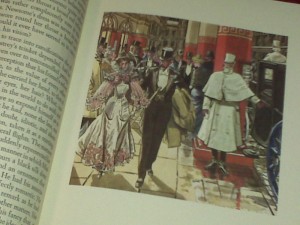

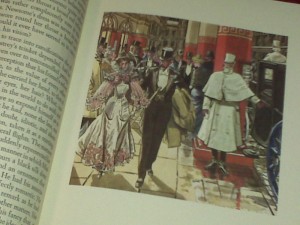

As in many Henry James novels, often the smallest gesture has the biggest import, backed by layers of meaning, history, implication and nuance. It can be a short, shared experience between two people, seemingly commonplace, but it immediately accelerates to a potent moment when given just a little backstory. James knew all about backstory, the bigger picture, the stuff rich stories are made of.

Martha Ullman West, Art Scatter’s favorite dance correspondent, emailed me soon after my story about trying to read James appeared in the O! books section of The Oregonian on Jan. 4 of this year.

Martha Ullman West, Art Scatter’s favorite dance correspondent, emailed me soon after my story about trying to read James appeared in the O! books section of The Oregonian on Jan. 4 of this year.

I had notified most people that I was including their comments in my story, but I didn’t say a thing to Martha. I left it all as a surprise.

She didn’t know that the fine edition of The Ambassadors that had belonged to her late husband, Frank West, would be featured so prominently.

She generously gave me that book after I told my woeful tale of my sad little copy from the library. I gave her a quart jar of my best dill pickles in return.

Soon after, Martha wrote: “Unbeknownst to you, I think the pickles were a completely appropriate gift, because Frank made pickles every summer until the last year of his life. Kosher dills were his specialty.”

My dad made pickles. Once.

It was just a few weeks after my mom had surgery to remove a large tumor from the middle of her brain when my aunt showed up at the house with a box full of pickling cukes.

Before my mom had surgery my family didn’t know how or if she would recover. We weren’t given any expectations. We didn’t know whether she’d be able to walk or talk. We were told the recovery process could take up to a year.

But only a few weeks after surgery my mom was up and about a bit. Oddly, the memory embedded most in my mind is my mom sitting on the front stoop of the house, a large bandage wrapped around her head, carefully trying to control her hand movements as she put smelly mothballs into pantyhose, tied them, and then buried them in the planters next to the stoop as a ruse to keep out the pesky squirrels that dug there all the time. It never worked. The squirrels just scratched aside the mothballs, one tied pantyhose after another, leaving the porch to smell like a nasty attic. My mom did all this while sitting rigidly straight and not bending over, because she risked her brain collapsing in and then the outside of it hemorrhaging. Which would have been bad. It could have killed her.

My dad, who was always antsy in the best of circumstances, carefully attended my mom and was determined to keep everything as normal as possible. He never stopped moving. He did all the things my mom had always done. He cooked. He cleaned. He couldn’t keep himself busy enough.

And then my aunt showed up with cucumbers. When my dad asked what he was supposed to do with them, my aunt replied that my mom always made pickles.

And so she had. Every summer. Along with canned peaches and pears.

Bread-and-butter pickles were her specialty. They’re the ones with sliced cucumbers and soft streamers of onions and a bunch of mustard seeds and peppercorns that look like confetti. Those pickles were always in our pantry and in the fridge. They were always in fancy dishes on holiday tables. I had never known them not to be there.

Bread-and-butter pickles were her specialty. They’re the ones with sliced cucumbers and soft streamers of onions and a bunch of mustard seeds and peppercorns that look like confetti. Those pickles were always in our pantry and in the fridge. They were always in fancy dishes on holiday tables. I had never known them not to be there.

And I had never known my dad to command the mottled black enamel canner until that summer. He made batch after batch of bread-and-butter pickles. The jars started lining up on the counter and they started to pop as they sealed. My dad would say, “Did you hear that? They go ‘pop, pop, pop.'” I would laugh and say, “How was that again?” He would repeat it: “They go ‘pop, pop, pop!‘”

After a day or two he had stacks of jars, each labeled with his tidy uppercase printing.

After a few months he started to have headaches. When he finally went to the doctor, he was immediately given prescriptions and an appointment with a neurosurgeon. He had a brain tumor.

We could tell the rhythm was completely different this time from when my mom had surgery. With her, doctors weren’t hurried about setting dates, taking plenty of time to carefully map her brain to figure out the least invasive path. They knew her tumor was most likely benign and slow-growing. With my dad, appointments were scheduled right away.

His surgery, just days after his diagnosis, confirmed what we had suspected: The tumor was malignant. He had one of the most aggressive types of brain cancer. We were told he would probably have a year.

My dad, who had so attentively taken care of my mom, not just after her surgery but for all the months and years before it when her behavior was so goofy and we didn’t know why, now had to be taken care of. And my mom, just months out of surgery and still recovering herself, suddenly had to take care of my dad.

By the time pickling cukes were in their prime again my dad was wobbly and sleeping more. He never made pickles again.

So you see, Martha, pickles were a perfectly appropriate gift. Unbeknownst to you, my dad made pickles. Just once. Near the last year of his life. Bread-and-butters were his specialty.

When The Large Smelly Boys bicker in the car, I hit play and they magically silence before the almighty audio book. Nancy Farmer, god bless her. Past summers we plowed through her The Sea of Trolls and The Land of the Silver Apples. Just to be safe, we have along her The Islands of the Blessed on iPod, CD and hard copy. Thank heavens, because we’ve used all of them. In less than a week, the hard copy was devoured by two members of the Scatter Family.

When The Large Smelly Boys bicker in the car, I hit play and they magically silence before the almighty audio book. Nancy Farmer, god bless her. Past summers we plowed through her The Sea of Trolls and The Land of the Silver Apples. Just to be safe, we have along her The Islands of the Blessed on iPod, CD and hard copy. Thank heavens, because we’ve used all of them. In less than a week, the hard copy was devoured by two members of the Scatter Family.

Martha Ullman West, Art Scatter’s favorite dance correspondent, emailed me soon after

Martha Ullman West, Art Scatter’s favorite dance correspondent, emailed me soon after Bread-and-butter pickles were her specialty. They’re the ones with sliced cucumbers and soft streamers of onions and a bunch of mustard seeds and peppercorns that look like confetti. Those pickles were always in our pantry and in the fridge. They were always in fancy dishes on holiday tables. I had never known them not to be there.

Bread-and-butter pickles were her specialty. They’re the ones with sliced cucumbers and soft streamers of onions and a bunch of mustard seeds and peppercorns that look like confetti. Those pickles were always in our pantry and in the fridge. They were always in fancy dishes on holiday tables. I had never known them not to be there.

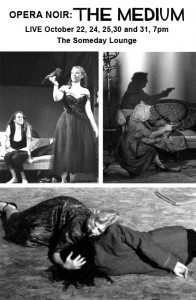

“This score is my bible,”

“This score is my bible,”  Things have been busy here at Scatter Central the last few days; so busy that we haven’t had a chance to post since we left poor

Things have been busy here at Scatter Central the last few days; so busy that we haven’t had a chance to post since we left poor Over at his alternate-universe home,

Over at his alternate-universe home,  Meanwhile, who’d have guessed that the path to understanding

Meanwhile, who’d have guessed that the path to understanding