“Funes remembered not only every leaf

of every tree of every patch of forest,

but every time he had perceived

or imagined that leaf. “

-Jorge Luis Borges “Funes, His Memoryâ€

I turn sixty today and my memory plays tricks. At any moment I can forget a word, like “deck†or “cup†or “knife.†It’s there in my mind’s eye, a clear picture, but the word refuses to skip past the tip of my tongue to finish my thought.

I turn sixty today and my memory plays tricks. At any moment I can forget a word, like “deck†or “cup†or “knife.†It’s there in my mind’s eye, a clear picture, but the word refuses to skip past the tip of my tongue to finish my thought.

I struggle with the word “sofa,†in part because growing up in my family in my corner of the Midwest it was called a “davenport.â€

In frustration, I ask for a little help. “It’s that thing with numbers, on the car,†meaning license plate. “Wouldn’t it be easier to just say ‘license plate’?†responds my unsympathetic son.

But there are other memory flips that I think of as structural. I catch myself bewildered whether I’ve actually done something I meant to or merely think I have. Did I lock the door? Turn off the downstairs light? Or I turn to do one of those things and realize I did it moments before.

At the health club I hang my towel on a hook and unless I consciously make a mental note, look back and confirm its position and signature fold, I’ll emerge from the shower with no idea which towel is mine. By habit I have a primary hook and a back-up, but in these moments, who knows? At times I just grab and run. Folks can be very unforgiving if you use their towel.

And here’s another odd short-term memory thing. I read a chapter in a book. A half hour later I skim the same passage. Some details are as if new, others spring up vividly in memory, but with the same patina of recognition as memories that are ten or twenty or thirty years old.

And there’s that curious feeling of panic, forgetting the names of folks I know well when it’s time to introduce them. Or forgetting a person’s name fifteen seconds after we’re introduced. That may be as much social anxiety as faulty memory. But even in moments of quiet reflection, I’ll stammer. Who’s the female lead in my favorite movie, “Love at Large� Elizabeth Something? Ah, yes. Perkins. Who wrote “One Hundred Brothers� James Wilcox? No, he wrote “Modern Baptists.†The other quirky writer working in utter obscurity is Donald Antrim.

This is disconcerting because my mind for books and authors, even the most marginal ones I’ve never read or never will read, is usually of the same absorbent variety as others’ minds for baseball trivia or wines. Now that faculty skips a beat, too. So folded in my billfold, tattered and worn, I keep a short list of books, writers, movies and CDs, so I can browse in book or music stores without panic.

Finding myself in this predicament more and more often, it’s no wonder Douwe Draaisma’s book Why Life Speeds Up As You Get Older: How Memory Shapes Our Past (Cambridge University Press, $18.99) caught my eye in an ad in The London Review of Books. I neglected to note it on my billfold crib sheet, though, so a day or two later in the bookstore I recalled, vaguely, “Why Memory, Something, Something…†and no more (until I looked it up again in the Review).

Finding myself in this predicament more and more often, it’s no wonder Douwe Draaisma’s book Why Life Speeds Up As You Get Older: How Memory Shapes Our Past (Cambridge University Press, $18.99) caught my eye in an ad in The London Review of Books. I neglected to note it on my billfold crib sheet, though, so a day or two later in the bookstore I recalled, vaguely, “Why Memory, Something, Something…†and no more (until I looked it up again in the Review).

Continue reading TURNING 60: YOU MUST REMEMBER THIS →

Nell Warren’s paintings at PDX Contemporary Art have been on my mind all weekend. “Quandaries†they are called. I’ve played with that notion, echoing the word in the “quaint†look the paintings have or the “boundary” Warren blurs between abstraction and representation. My doubt not about if I like them but why. In her artist’s statement, Warren says her work reflects a “delicate balance of serendipity and intent.” That captures perfectly the chance and causal links in my own reaction to the paintings.

Nell Warren’s paintings at PDX Contemporary Art have been on my mind all weekend. “Quandaries†they are called. I’ve played with that notion, echoing the word in the “quaint†look the paintings have or the “boundary” Warren blurs between abstraction and representation. My doubt not about if I like them but why. In her artist’s statement, Warren says her work reflects a “delicate balance of serendipity and intent.” That captures perfectly the chance and causal links in my own reaction to the paintings.

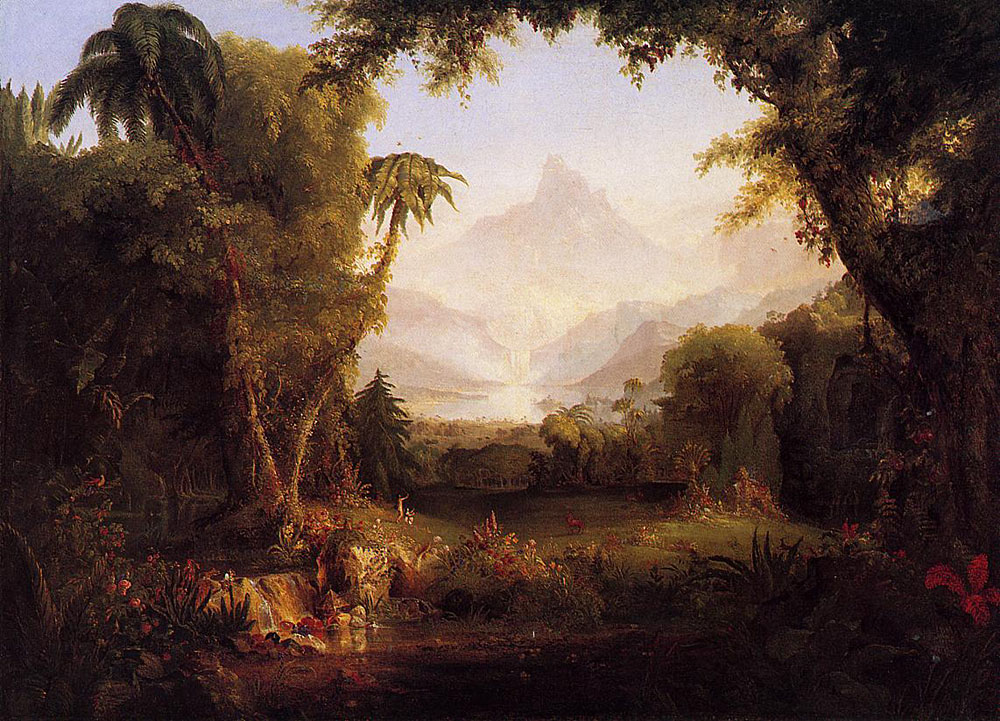

Dismantling Paradise is hard work. Accomplishing it by proxy, such as in writing a novel, also takes its toll. Perhaps that’s why

Dismantling Paradise is hard work. Accomplishing it by proxy, such as in writing a novel, also takes its toll. Perhaps that’s why