By Bob Hicks

The family tree just keeps getting bigger and bigger. Or the roots get more and more tangled.

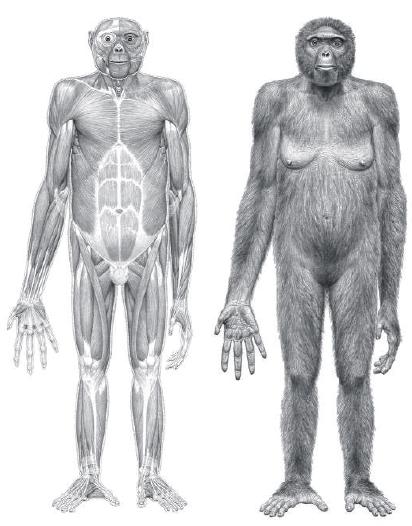

This morning’s most intriguing news was the revelation that, yes indeed, Neanderthals seem to be among our ancestors. At least, a team of biologists doing DNA analysis of Neanderthal bones has determined tentatively that between 1 and 4 percent of non-African contemporary humans’ genome derives from that brawny, slope-headed side of the family. Once upon a time most scientists pretty much figured there’d been intermingling. Then they decided there hadn’t been. Now, it seems, caveman sex was pretty liberal, after all.

Several versions of this story are floating around. We like Nicholas Wade’s report in the New York Times, because it’s complete for a general audience and comes with the necessary cautions that more research needs to be done and not all scientists agree that the evidence leads to the conclusion. Even in matters sexual, peer review is important.

Here at Art Scatter World Headquarters we have a longstanding interest in the prehistoric links between culture and biology. We’ve talked about them in relationship to natural selection in the Pleistocene era and celebrated the discovery of Ardi, our 4.4 million-year-old beauty of a cousin. Something’s been making the world go ’round for a long, long time.

We also note with gleeful irony that today’s announcement comes as bad news for the rear-guard intellects of the Aryan Nations: Because this interbreeding hanky panky took place in the Middle East, after humans had migrated there from Africa but before the wanderers had split off into their European and Asian arms, the shared genetic material isn’t found south of the Mediterranean. In other words: If there’s such a thing as a “pure” race, it’s in Africa. Ha!

*

Illustration: National Aeronautics and Space Administration artist’s rendition of a family of Neanderthals about 60,000 years ago. The extinct animals of the Pleistocene epoch pictured are the Woolly Mammoth, the Bush Antlered Deer, and the Sabre Toothed Cat. Pleistocene animals in this image that still exist are the Eurasian Horse, the Oryx, the Banded Lemming and the Musk Ox. Some of the plant life of the Pleistocene epoch consisted of grasses (which did not exist until this time), ferns, trees, sedges and shrubs.

The Art Instinct talks a lot about the evolutionary bases of the urge to make art: the biological hard-wiring, if you will. Dutton likes to take his readers back to the Pleistocene era, when the combination of natural selection and the more “designed” selection of socialization, or “human self-domestication,” was creating the ways we still think and feel. To oversimplify grossly, he takes us to that place where short-term survival (the ability to hunt; a prudent fear of snakes) meets long-term survival (the choosing of sexual mates on the basis of desirable personal traits including “intelligence, industriousness, courage, imagination, eloquence”). Somewhere in there, peacock plumage enters into the equation.

The Art Instinct talks a lot about the evolutionary bases of the urge to make art: the biological hard-wiring, if you will. Dutton likes to take his readers back to the Pleistocene era, when the combination of natural selection and the more “designed” selection of socialization, or “human self-domestication,” was creating the ways we still think and feel. To oversimplify grossly, he takes us to that place where short-term survival (the ability to hunt; a prudent fear of snakes) meets long-term survival (the choosing of sexual mates on the basis of desirable personal traits including “intelligence, industriousness, courage, imagination, eloquence”). Somewhere in there, peacock plumage enters into the equation.

Lectures, tours, workshops, open rehearsals: If it’s a behind-the-scenes peek, we’re there. It’s not enough just to see the finished project. We want to know how it got there.

Lectures, tours, workshops, open rehearsals: If it’s a behind-the-scenes peek, we’re there. It’s not enough just to see the finished project. We want to know how it got there. So let’s take the pressure off and take a relaxed look at how this art stuff really works. That’s part of the idea behind

So let’s take the pressure off and take a relaxed look at how this art stuff really works. That’s part of the idea behind

One of Art Scatter’s favorite blogs is

One of Art Scatter’s favorite blogs is  Their latest consideration is another of my favorites at the museum,

Their latest consideration is another of my favorites at the museum,

Yes, Mule Days. As in Harry S Truman. As in

Yes, Mule Days. As in Harry S Truman. As in  This is not the Sport of Kings, with sleek beauties like Secretariat to give an aesthetic gloss to the gambling and occasional gore. This is mules, the sterile offspring of male donkeys and female horses, who are strong and capable but also awkward and funny-looking, with heads too big for their bodies and ears too long for their heads.

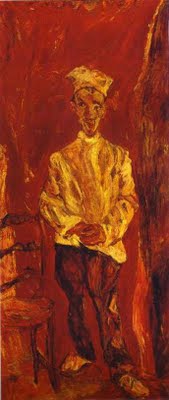

This is not the Sport of Kings, with sleek beauties like Secretariat to give an aesthetic gloss to the gambling and occasional gore. This is mules, the sterile offspring of male donkeys and female horses, who are strong and capable but also awkward and funny-looking, with heads too big for their bodies and ears too long for their heads. Today, in the throes of an infernal Pacific Northwest heat wave that has the thermometer rattling up toward 107, that red-baked head is on my mind again. Kind of blue, kind of hot, an oddly triumphal moan, mixed of resignation and endurance and somehow coming out on the sweet side of things: I ain‘t dead.

Today, in the throes of an infernal Pacific Northwest heat wave that has the thermometer rattling up toward 107, that red-baked head is on my mind again. Kind of blue, kind of hot, an oddly triumphal moan, mixed of resignation and endurance and somehow coming out on the sweet side of things: I ain‘t dead. Here in the Art Scatter sauna we wouldn’t stoop to

Here in the Art Scatter sauna we wouldn’t stoop to