By Bob Hicks

Mr. Scatter has been thinking about wit lately, partly because he’s been rereading Jane Austen‘s novel Emma and partly because, as regular Scatterers know, he attended the opera last Friday evening to see and hear Rossini‘s splendidly whimsical opera buffa The Barber of Seville.

Both works, as the globe-trotting Mrs. Scatter has pointed out, made their debuts in 1816, which was technically part of the 19th century. But both feel more like products of the 18th century (as the Edwardian years seem an extension of the 19th century, which could be said to have ended in 1914).

Both works, as the globe-trotting Mrs. Scatter has pointed out, made their debuts in 1816, which was technically part of the 19th century. But both feel more like products of the 18th century (as the Edwardian years seem an extension of the 19th century, which could be said to have ended in 1914).

Certainly Rossini’s opera, with its libretto by Cesare Sterbini adapted from a 1775 comedy by Pierre Beaumarchais, is fully in the spirit of the Age of Reason, embellished by a happy nod back to the 17th century theatrical glories of English Restoration comedy and the French satires of Moliere. And Austen’s class comedies seem slung somewhere between classic Enlightenment intellectual balance (Haydn, Swift, Mozart, Gibbon, Pope) and the surge of Romanticism that would engulf the 19th century (Beethoven, Byron, Mary Shelley, Harriet Beecher Stowe, on down to Wagner).

Austen’s comedies may be the most precise and practical romances ever written. Obsessed with the often foolishly claustrophobic concerns of a narrow slice of self-satisfied society, they’re also worldly. Within the confines of that small society she discovers a measured universe of human possibility, from the perfidious to the noble. And she does it with one of the slyest, keenest raised eyebrows in all of literature.

Austen’s comedies may be the most precise and practical romances ever written. Obsessed with the often foolishly claustrophobic concerns of a narrow slice of self-satisfied society, they’re also worldly. Within the confines of that small society she discovers a measured universe of human possibility, from the perfidious to the noble. And she does it with one of the slyest, keenest raised eyebrows in all of literature.

Entering Austen’s world takes a certain amount of patience (it spins at the speed of a barouche carriage, not a supersonic transport; you must make peace with its rhythm) and some very smart people simply never make the transition. “Why do you like Miss Austen so very much?” Charlotte Bronte queried the philosopher and critic (and George Eliot’s live-in lover) G.H. Lewes in a letter from 1848. “I am puzzled on that point … I should hardly like to live with her ladies and gentlemen, in their elegant but confined houses … Miss Austen is only shrewd and observant.”

This four-hand feat, by the way, will come just before Mrs. Scatter’s departure on her own quest, this one to far London town on the trail of Tates

This four-hand feat, by the way, will come just before Mrs. Scatter’s departure on her own quest, this one to far London town on the trail of Tates  Ms. Alsop is

Ms. Alsop is  It’s the latest in Eric Hull‘s

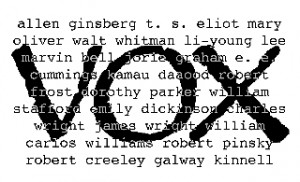

It’s the latest in Eric Hull‘s  Waterbrook is basically a room with an entrance area and a door leading to what serves as a green room for the performers. Somewhere around the corner, down a broad-plank floor, is a restroom. On Saturday the performance space had a few rows of folding chairs for the spectators, a lineup of music stands up front for the six performers, and three chairs to the side for the performers who occasionally sat a poem out. In other words: all the tools you really need to create some first-rate performing art.

Waterbrook is basically a room with an entrance area and a door leading to what serves as a green room for the performers. Somewhere around the corner, down a broad-plank floor, is a restroom. On Saturday the performance space had a few rows of folding chairs for the spectators, a lineup of music stands up front for the six performers, and three chairs to the side for the performers who occasionally sat a poem out. In other words: all the tools you really need to create some first-rate performing art.

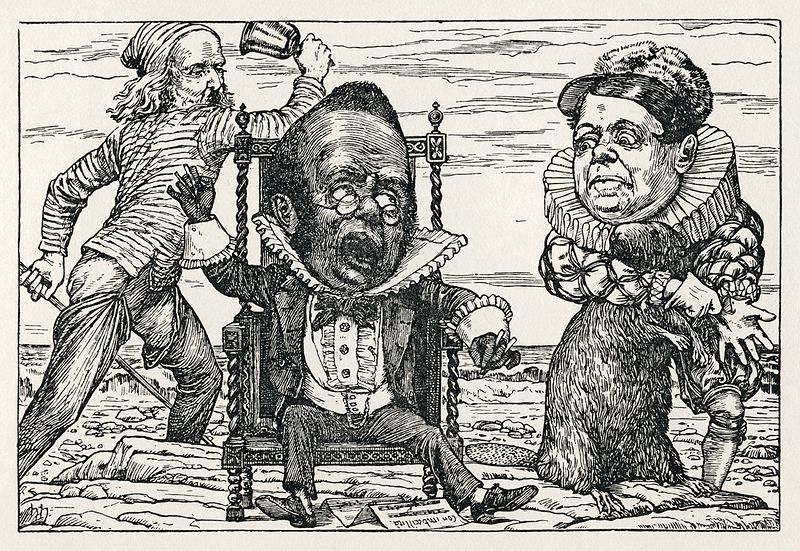

Witnesses — those “I alone am escaped to tell you” chroniclers of catastrophe and adventure — are crucial figures in the world of the imagination. From the cautioning choruses of Greek tragedies to Melville’s wide-eyed sailor Ishmael, we’re used to the idea of the witness as a cornerstone of civilized life.

Witnesses — those “I alone am escaped to tell you” chroniclers of catastrophe and adventure — are crucial figures in the world of the imagination. From the cautioning choruses of Greek tragedies to Melville’s wide-eyed sailor Ishmael, we’re used to the idea of the witness as a cornerstone of civilized life. From the lofty perch of the present we stand as witnesses to time, looking back on history, rewriting it as we gain new reports from the trenches and rethink what we’ve already seen. We judge, revise, rejudge: In the courtroom of culture, the jury never rests.

From the lofty perch of the present we stand as witnesses to time, looking back on history, rewriting it as we gain new reports from the trenches and rethink what we’ve already seen. We judge, revise, rejudge: In the courtroom of culture, the jury never rests.