Muleskinner Blue Skies: The Wallowas in summer as seen from the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area. Wikimedia Commons.

While all you young buckaroos are heading into cowboy country for the 99th annual Pendleton Round-Up and Happy Canyon Pageant starting Wednesday, Mr. Scatter will be stuck inside of Portland with the Round-Up Blues again. I’ll be missing the roping, the trick riding, the bronc busting, the prodigious after-hours cheap bourbon guzzling, and all those other enduring arts of the untamed West.

So last weekend, on a trip to Enterprise in the Wallowa Mountains — 100-odd miles east of Pendleton, which put me really into ranch country — I compensated by heading for the Wallowa County Fairgrounds and the 29th annual Hells Canyon Mule Days.

Yes, Mule Days. As in Harry S Truman. As in Francis the Talking. As in 20 Mule Team Borax. As in stubborn as a. As in Bing Cosby’s tune about “an animal with long funny ears” whose “back is brawny and his brain is weak” — a gross misrepresentation of this hardworking beast, which is indeed brawny but is anything but weak-minded: It’s much too smart to give in to a mere human being without a fight.

Yes, Mule Days. As in Harry S Truman. As in Francis the Talking. As in 20 Mule Team Borax. As in stubborn as a. As in Bing Cosby’s tune about “an animal with long funny ears” whose “back is brawny and his brain is weak” — a gross misrepresentation of this hardworking beast, which is indeed brawny but is anything but weak-minded: It’s much too smart to give in to a mere human being without a fight.

Sitting in the grandstands and watching the curious backward dance of one unhappily saddled pack animal, I got the very strong feeling that mules are not meant for racing. And I reached the inescapable conclusion that, whatever else the mule’s multiple virtues, there is something inescapably comic — Sisyphean, even — about trying to coax it into performing the sort of rodeo tricks that seem like catnip to a horse.

This particular beast was a stocky, handsome, muscular white specimen of the species, and I have no doubt that when called upon it can haul its weight in moonshine over tricky terrain. But when its rider tried to coax it to the white chalk starting line for the pole bending competition, the mule instead shied from the bit and stepped back, back, backward, arching its neck and tossing its head in protest, until it rammed its rump into the rail that separates the field from the track. Minding its so-called “master” was not on its agenda on this Sunday afternoon.

Oddly, I admired the beast.

Mule Days here in Enterprise, in the gorgeous high country of far northeastern Oregon that is still rightly lamented by the Nez Perce Indians who were run off their land 130 years ago by the U.S. Cavalry, offer a lot of other attractions. A Dutch oven cooking competition. A quilt exhibition. Cowboy poets. Hand-tooled saddles and other western gear for sale. Unending country music over the loudspeakers. All the fairground snacks your stomach can handle.

But people, keep your eyes on the main event here: galloping mules!

This is not the Sport of Kings, with sleek beauties like Secretariat to give an aesthetic gloss to the gambling and occasional gore. This is mules, the sterile offspring of male donkeys and female horses, who are strong and capable but also awkward and funny-looking, with heads too big for their bodies and ears too long for their heads.

This is not the Sport of Kings, with sleek beauties like Secretariat to give an aesthetic gloss to the gambling and occasional gore. This is mules, the sterile offspring of male donkeys and female horses, who are strong and capable but also awkward and funny-looking, with heads too big for their bodies and ears too long for their heads.

And from what I saw on Sunday, you don’t coax a mule. It more or less decides on its own whether it feels like playing the game on any given day. Understand, I speak from base ignorance. Mrs. Scatter and OED, our Older Educated Daughter, have seen me in the saddle, and after 20 years they still snicker at the memory. There are intricacies and even basic principles about these animals that I simply do not understand. So, muleskinners and other animal handlers, please forgive my misinterpretations of the muling life. And bear in mind that of the many skills tested during Hells Canyon Mule Days, pole bending is the only competition that I witnessed: For all I know, when it comes to the full-tilt boogie the mule is more beautiful than an Arabian, more skillful than a quarterhorse. But this is what I saw.

Continue reading Or would you rather swing on a star? Taming the ornery mule in Oregon high country

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind.

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind. In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose

In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose

Nobody seems to remember anymore what the fabled bull and bear stand for, the story comments, and they got that right: If investors and manipulators hadn’t conveniently forgot that the bull periodically and inevitably transforms into a bear, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now. Optimism is a lovely thing, but not when it doesn’t have its feet on the ground.

Nobody seems to remember anymore what the fabled bull and bear stand for, the story comments, and they got that right: If investors and manipulators hadn’t conveniently forgot that the bull periodically and inevitably transforms into a bear, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now. Optimism is a lovely thing, but not when it doesn’t have its feet on the ground. Readers of Laura Grimes’ recent post

Readers of Laura Grimes’ recent post

It was early 2002. Mr. Scatter and I and the large smelly boys – who were not so large and not so smelly back then – were driving several hours north to visit family. To visit my mom, in fact. The not-so-large not-so-smelly boys must have been blessedly quiet in the backseat for a long stretch of road. We’ll just chalk that up to divinity and not ask why.

It was early 2002. Mr. Scatter and I and the large smelly boys – who were not so large and not so smelly back then – were driving several hours north to visit family. To visit my mom, in fact. The not-so-large not-so-smelly boys must have been blessedly quiet in the backseat for a long stretch of road. We’ll just chalk that up to divinity and not ask why.

Why not turn cadavers into posed objects for museum display, as hugely popular shows such as

Why not turn cadavers into posed objects for museum display, as hugely popular shows such as  Here’s the thing. Arts people have been around a very long time, and no matter how hard you kick ’em around, they keep popping back up.

Here’s the thing. Arts people have been around a very long time, and no matter how hard you kick ’em around, they keep popping back up. Sojourn is a Portland-based company that tours the country, developing and performing community-based plays that usually coalesce around specific themes. For the last year, among a myriad of other activities, it’s been working on a new piece called On the Table that looks at food, and how it’s grown and distributed, and the choices we make about it, and the impact it has on various communities. A lot of field reporting (in this case, literally) goes into a typical Sojourn show, and that takes time and resources. Company director Michael Rohd figures the project has another year to go: “The show will happen Summer 2010 simultaneously in PDX and a small town 50 miles from PDX, and explores the urban/rural conversation in Oregon, culminating with a bus trip for both audiences and a final act at an in-between site,” he says.

Sojourn is a Portland-based company that tours the country, developing and performing community-based plays that usually coalesce around specific themes. For the last year, among a myriad of other activities, it’s been working on a new piece called On the Table that looks at food, and how it’s grown and distributed, and the choices we make about it, and the impact it has on various communities. A lot of field reporting (in this case, literally) goes into a typical Sojourn show, and that takes time and resources. Company director Michael Rohd figures the project has another year to go: “The show will happen Summer 2010 simultaneously in PDX and a small town 50 miles from PDX, and explores the urban/rural conversation in Oregon, culminating with a bus trip for both audiences and a final act at an in-between site,” he says.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8.

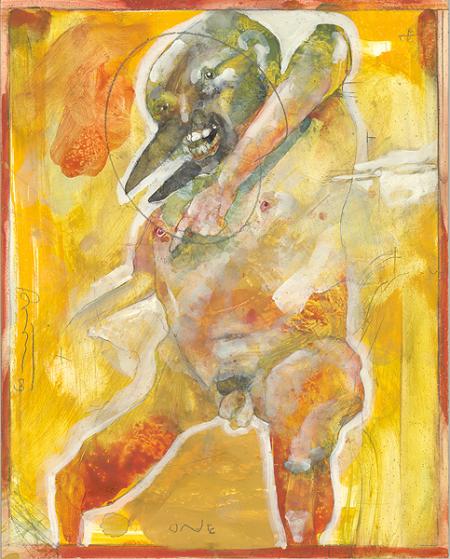

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8. But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.