I’m just trying to do this jig-saw puzzle

Before it rains anymore

– M. Jagger / K. Richards “Jigsaw Puzzleâ€

Ours is a family of re-puzzlers. Last holiday our sons, both in their mid-twenties, spent two days working through our old puzzles, beginning with the extra large-piece “Masters of the Universe,†a “battle royal†featuring He-Man and two dozen other trademarked Mattel heroes of the day (circa 1983). From there they moved to “G.I. Joe Battles Cobra Command,†four puzzles that, when completed, can be interlocked to form a large mural depicting all-out war on land and sea and in the air. These boys have always been deliberate, methodical re-puzzlers. As youngsters they would build them, tear them down and build again. As adults they are also deliberate about seeming disengaged; they are handling memories, after all, not puzzle pieces.

My wife and I joined them on the adult puzzles, some we’ve had since the late 1960s, when we were first married and a bottle of wine and a good puzzle were an evening’s entertainment: “Fisherman’s Wharf,†in Monterey, California, the way it looked when we lived there; “Five-Clawed Dragon,†a detail from an embroidered Chinese Imperial robe; and “St. George and the Dragon,†a photograph of a statuette owned by a Bavarian duke who lived during the time of Shakespeare.

Oh, we’ve had other, one-time puzzles, more than I’d want to count, but these are the ones we’ve kept and re-puzzled time and again. Life is like a jigsaw puzzle, I’ve thought. Not like a box of chocolates. The puzzle worked over and completed, and then un-puzzled and tossed back into its box, is the seven ages of man – the first youthful stammering returning to reclaim incoherence from the modest settled principles an adult pieces together once, maybe twice, in a life.

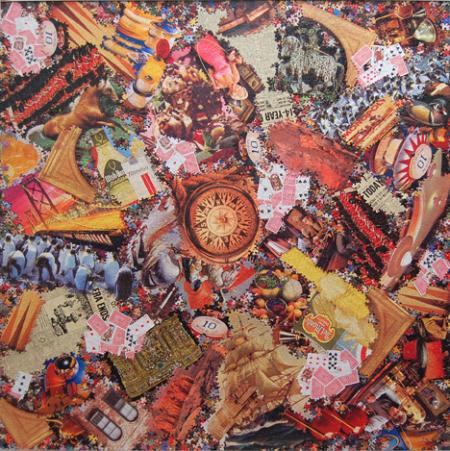

So I was curious to see Al Souza’s sculptural jigsaw puzzle collages showing at Elizabeth Leach Gallery this month. He uses commercial puzzles gathered from thrift stores and on E-bay, and some that acquaintances around the country find and assemble for him. He layers and juxtaposes parts of the puzzles in large scale works such as “Italian Dressing†(72†X 72â€, above), creating an explosion of slick images and bright colors that are the hallmark of commercial puzzles. Animals, clocks, landscapes, famous paintings and buildings, loopy holiday ribbon candy, toys and sports memorabilia – jumbled together in odd, surprising ways.

Continue reading Al Souza: The Puzzler’s Dilemma

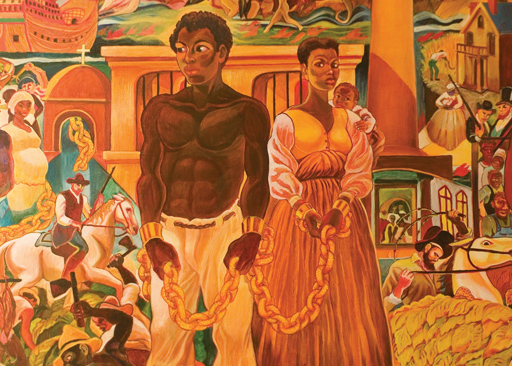

In this case the “Elephant,” left, and a rather pinkish one to boot, is one of Molly Vidor’s five mostly abstract paintings in a show called “Destroyer†now at

In this case the “Elephant,” left, and a rather pinkish one to boot, is one of Molly Vidor’s five mostly abstract paintings in a show called “Destroyer†now at