(Friend of Art Scatter Martha Ullman West, she who knows a plie from a pirouette like nobody’s business, has recently sojourned in her home town of NYC and brings us back this Big Apple journal from October 21 to November 5, 2008. The city seems familiar, but …)

Can you actually be a tourist in your home town? At times I certainly felt like one on my recent visit to the city in which I grew up, quite a long time ago.

Can you actually be a tourist in your home town? At times I certainly felt like one on my recent visit to the city in which I grew up, quite a long time ago.

I attended a performance in a theater new to me — the Rose, where I heard a stellar rendition of Bach’s St. John’s Passion by Musica Sacra in a space that is usually relegated to jazz. And I felt so even more when I had to ask not one but two of the hordes of security police on Wall Street to direct me to One Chase Manhattan Plaza, the bank’s headquarters and the location of the Ballet Society/New York City Ballet archives. These are not exactly housed in a vault, but they have been relegated to the fifth floor sub-basement of that temple to Mammon for good reason: a board member of the Balanchine Foundation arranged for donated space.

There couldn’t be a worse place to work– no air, harsh fluorescent lights, a desk that was too high, a chair that was too low. But it was a gold mine of information regarding American Ballet Caravan‘s 1941 tour of South America, the first North American ballet company to go to the region, on a goodwill tour arranged through Nelson Rockefeller by Lincoln Kirstein for the overt purpose of a cultural exchange, and the covert purpose of undercutting anti-American propaganda disseminated by Germany before Pearl Harbor.

I spent two days delving into boxes of documents and photographs, physically uncomfortable, but psychically happy as the proverbial clam. The archivist, Laura Raucher, who has a degree in the science of dance from the University of Oregon, photocopied anything I wanted and spent more than an hour searching the database for the heights of various Balanchine ballerinas, information needed for another project.

I spent two days delving into boxes of documents and photographs, physically uncomfortable, but psychically happy as the proverbial clam. The archivist, Laura Raucher, who has a degree in the science of dance from the University of Oregon, photocopied anything I wanted and spent more than an hour searching the database for the heights of various Balanchine ballerinas, information needed for another project.

A few days later I was at the Jerome Robbins Dance Division in the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center, for which I daily thank Robbins, whose royalties support arguably the best dance library in the world, looking at film of Marie Jeanne coaching today’s dancers in her role in Balanchine’s Concerto Barocco, created for her before that 1941 tour. I learned that the ballet, a high-speed visualization of the Bach Double Violin concerto, used to be performed even faster than it is today. The library is an extremely comfortable place to work, fluorescent lights notwithstanding, but there you must do your own photocopying and pay for it, sigh. Always something.

Another day Melissa Hayden‘s book, written for young ballet students, and not available anywhere else, shed new light on Todd Bolender‘s The Still Point. Another book, Robert Tracey’s Balanchine’s Ballerinas, is thank God available at the Multnomah County Library, because the Art Scatter cold, or some other cold, felled me and prevented me from reading it there.

At the Dance Collection I am not a tourist. It wasn’t there when I lived in NY (Lincoln Center opened the year after I left, the library sometime later) but I’ve worked there frequently over the years and am known to the staff, including the ever-helpful Charles Perrier, who inquired, when I told him I’d been at the NYCB archive, if I’d dodged any bodies falling out of windows on Wall Street.

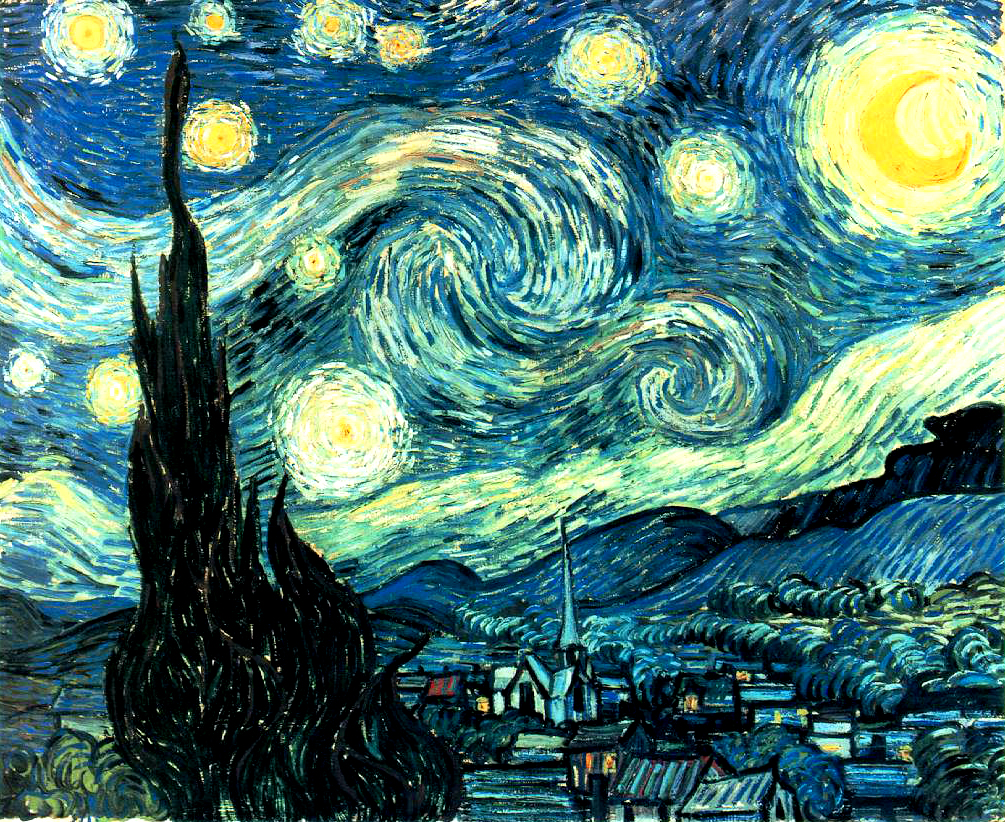

Nor am I a tourist at MOMA, even in its remodeled version, though I had to ask where I could find the much beloved Matisse Red Room. I was there with a friend to see Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night with hordes of tourists whom I resented, because the exhibition is hung in quite a cramped fashion and very difficult to see. Nevertheless, it’s a magnificent collection of paintings with nary a sunflower among them. Van Gogh, I realized, could be put in a continuum of painters of light that includes Rembrandt, his countryman, but also J.M.W. Turner. The exhibition includes some very early paintings, quite academic, and if you look at the dates you realize that 1898 and ’99 were significant years — that’s when the brushstrokes changed.

I’m not a tourist at New York City Center, either, where in the Fifties I sat in $1.75 seats in the second balcony to see Balanchine’s Agon in its premiere season and other wonders of the NYCB rep. This time I was there in the orchestra one night, the mezzanine the second, to see two performances by American Ballet Theatre, which now has a fall season there for the purpose of performing programs of short works, rather than the evening-length story ballets that are the centerpiece of the spring season at the Metropolitan Opera.

On Halloween night, the company, in honor of Antony Tudor‘s centenary, performed a full evening of his sometimes spooky works that included a film tribute titled Antony Tudor: American Ballet Theatre’s Artistic Conscience.

On Halloween night, the company, in honor of Antony Tudor‘s centenary, performed a full evening of his sometimes spooky works that included a film tribute titled Antony Tudor: American Ballet Theatre’s Artistic Conscience.

The 1936 Jardin aux Lilas (Lilac Garden) and 1942 Pillar of Fire, the first ballet the Englishman made in the United States, are manifestations of that conscience. Neither ballet is exactly what Balanchine called an applause machine; both dig deep into sexual repression, duty versus love, the perils of loneliness, social constrictions vs. individual freedom.

Jardin is set in Edwardian England. The cast is small, and the names of the protagonists tell the story and set the mood: Caroline, the Bride to Be; Her Lover, The Man She Must Marry; An Episode in his Past, (AKA the other woman); eight friends and relations, guests at a pre-nuptial party in a garden perfumed with lilacs and regret. Chausson‘s score suggests banked fires; Tudor’s choreography, based on the classical vocabulary with extremely intricate pointe work for the women, is modernist, sometimes Graham-like. This is considered the first psychological ballet, and it’s about real people, torn between duty and love. We are unlikely to see it in Portland, although Oregon Ballet Theatre has several dancers who would do it well. San Francisco Ballet, however, will perform it in the spring.

Pillar of Fire is set to a wrenching score by Schoenberg. I saw it twice, with Gillian Murphy and Julie Kent alternating in the role of Hagar. About a young woman driven by anxiety about following in the footsteps of her spinster older sister — reinforced by the flirtatious behavior of her younger sister with the object of her affections, titled The Friend — Pillar vividly evokes small-town America, where everybody knows everything about everybody. “Now I know exactly why my mother left Adrian, Michigan in 1930 and never went back,” I whispered to a friend halfway through the ballet.

Hagar “gives herself,” in the words of the libretto, “to one she does not love,” with the predictable gossip-ridden results, although unlike Jardin‘s unhappy conclusion, Pillar ends happily, with Hagar comforted by, then strolling into the sunset with, the Friend. Murphy was wonderful in the role of Hagar, but Kent was superb the following night, partnered by the impeccable David Hallberg: Her performance was finely detailed, her anguish completely believable.

Some people find these ballets old-fashioned, dated, but if they’re performed with the same conviction as by those who originated these roles, they pierce the heart in the same way that OBT’s Alison Roper does when she dances Odette in Swan Lake, not exactly a contemporary role, either.

The all-Tudor evening also included a highly satirical work called The Judgement of Paris, with ABT artistic director Kevin Mackenzie in the role of an aging boulevardier getting drunk in a Paris cafe and choosing among three aging prostitutes, danced by former ABT dancers kathleen Moore (now the company’s executive director), Martine Van Hamel and Bonnie Mathis. All were having a high old time and it was fun, novelty that it is, to see, especially with the knowledge that Agnes deMille once performed in this work. Xiomara Reyes and Gennadi Saveliev danced the bedroom pas de deux from Tudor’s one-act Romeo and Juliet, set to a score by Frederick Delius, infusing their performance with the lyrical poignancy called for by the music and making me wish the whole ballet could be revived. Continuo, a late work Tudor made for his Juilliard students, reveals his command of classical technique in a piece about dancing itself. It was a pleasure to see all these works, by a 20th century master much neglected in recent years.

It was not a pleasure to see the premiere of Lauri Stallings‘ Citizen on the same program with Pillar Saturday night. Easily the worst ballet I’ve ever seen — and I’ve seen some doozies, and said so publicly, over the years — it is yet another example of deconstructed “classicism,” danced by the elegant Hallberg in a costume that made him look like an idiot, and four other oppressed dancers that included Paloma Herrera being yanked around while she mugged. The score, by Max Richter, was almost as awful and pretentious as the distorted choreography.

Two works by Twyla Tharp, along with Pillar, redeemed the program, particularly Baker’s Dozen, a joyously complex work to music by Willie “the Lion” Smith, and while it didn’t have the post-modern edginess it had in 1979 when Tharp’s company performed it, ABT’s dancers gave it a heartily earthbound rendition nevertheless. The program ended with Tharp’s Brief Fling, a tartan-clad romp to various Hibernian tunes, and a perfect closer.

Citizen, as well as a number of pieces on a modern dance program at Dance Theater Workshop seen earlier, provided ample evidence that you can see just as much mediocre to bad work in the so-called dance capital of the world as you can anywhere else, including Portland. Of course every capital has its seamy underbelly, so no surprise there. Titled 40UP, six pieces were either created or performed or both by dancers over 40, some of them superb. In Paradigm, an excerpt from a work in progress by Donald Byrd, Gus Solomons jr. was the picture of relaxed elegance in a movement dialogue with Michael Blake. That was the highlight of a basically boring evening, although Sleeping Giant, another excerpt from a work in progress by Lawrence Goldhuber, whom Art Scatter readers will remember from the days when Bill T. Jones came to town with his company, danced by the choreographer in a Jolly Green Giant costume and Arthur Aviles was well worth the 10 minutes of attention it demanded. Forget the rest; I had by the time I walked to the corner of Ninth Avenue to hail a cab.

It’s politically incorrect to the Nth degree, but I find myself dreading performances by artists with disabilities, though not to the degree that Arlene Croce did with Jones’s Still/Here. A performance of A.R. Gurney‘s drawing room–or clubhouse!–comedy The Middle Ages by Theater Breaking Through Barriers (formerly Theater by the Blind) changed my mind about that. It’s a smart and funny play, about a prodigal son who refuses to obey any rules, let alone the rules of the country club of which his family has been the mainstay for several generations, and the acting was wonderful, particularly by George Ashiotis as Charles, beleaguered father of Barney, breaker of rules but not faith. Ashiotis is blind, but I was completely unaware of it, thanks to the skillful direction by Ike Schambelan, who founded the company 29 years ago. And the costumes by Chloe Chapin, except for a non-regulation sailor’s cap, were out of this world.

TBTB is a highly respected off-Broadway company, and with good reason: Everyone involved knew exactly what they were doing.