The victim pulled the trigger on itself, detective Garth Clark says, but it was under the influence of Art.

That’s Art, no last name, sometimes known as Fine Art. And though the corpse keeps getting tricked out for public events like the stiff in the movie comedy Weekend at Bernie’s, the actual time of death was, oh, somewhere around 1995.

That, more or less, is the argument Clark gave to a packed and sometimes steaming house last night in the Pacific Northwest College of Art‘s Swigert Commons. Clark, a longtime gallery owner, curator and prolific writer on craft (the guy knows his porcelains), was lecturing on “How Envy Killed the Crafts Movement: An Autopsy in Two Parts,” and he meant every word of it.

As he delivered his wry and scholarly Molotov cocktail, Clark reminded me a bit of John Houseman in The Paper Chase, measured and severe but with a, well, crafty twist of humor to his delivery. He knew he was going to be tromping on some toes, and while he delighted in the process, he did so en pointe so as not to cause too many hurt feelings. “Hi, my name is Garth Clark,” he greeted the crowd. “I’m a recovering art dealer.”

What is this art envy? Good question.

What is this art envy? Good question.

Surely it has something to do with money. Clark quoted one excellent potter of his acquaintance who says he and his friends have a word for potters who make a living entirely from their craft. It’s unicorns, “because we’ve never seen one.”

And surely it has something to do with reputation, with being taken seriously. Artists are simply thought of more highly, as more creative beings, more intellectual, and therefore more important (and, let’s underscore, more worthy of high prices in exchange for their work).

Perhaps it has something to do with escaping an eternal past. “Craft has been overdosing on nostalgia,” Clark averred. “This is craft’s Achilles heel.” That’s not surprising, he added, since the modern movement (which he stretches back 150 years, a very long time for a movement of any sort) was born as a revival, and thus looking backwards from its beginning.

So, he said, somewhere around 1980 craftmakers simply started referring to what they did as art. Museums and other organizations began to drop the word “craft” from their names — sort of like snipping their horse-thieving uncle from the family tree. For a few genuine artists who were trapped by their association with craft — people like Jun Kaneko and Robert Arneson — it was an escape with just cause. For others, it was wishful thinking. “Craft was strongly and sometimes pretentiously influenced by fine art,” Clark said, “but it did not cross the line to become fine art.”

For a lot of people in the audience, them was fightin’ words. What did Clark mean by “craft,” anyway? One object-maker drew applause when she commented that, when she’s in the studio, she doesn’t even think about whether she’s making art or craft, she just thinks about what she’s working on. And there was some sentiment that Clark was making a fuss about something that was really just about words and categories, things that come after the fact. “Everything he’s saying is coming from a gallery owner’s point of view,” the woman sitting next to me whispered in a huff.

For a lot of people in the audience, them was fightin’ words. What did Clark mean by “craft,” anyway? One object-maker drew applause when she commented that, when she’s in the studio, she doesn’t even think about whether she’s making art or craft, she just thinks about what she’s working on. And there was some sentiment that Clark was making a fuss about something that was really just about words and categories, things that come after the fact. “Everything he’s saying is coming from a gallery owner’s point of view,” the woman sitting next to me whispered in a huff.

And there might be some truth to that. Still, Clark insisted that categories are vital, and they are real. “Ultimately there is something called craft and there is something called art,” he said. “And there’s nothing wrong with that.”

What, then, is the difference? When it came right down to it, Clark had a tough time describing exactly what craft is. And in a sense, he blamed that on craftmakers, because they themselves had abandoned the word. After that, he said, “It was almost impossible to write honestly about a field that pretended to be something else.”

Here and there at Thursday’s event — the annual Jamison Lecture, presented by PNCA, the Museum of Contemporary Craft and the Oregon School of Art and Craft — he seemed to hint that craft is meant for home decoration (but so, of course, are paintings and small-scale sculptures). He got a little closer when he said that craft is a visual art that has “a close and intimate relationship with materials and processes” — in other words, made by hand. (Although a fair share of goods from the Arts & Crafts Movement, such as William Morris‘s intricate wallpapers, was designed by hand and produced by machine.)

And craft’s stress on physicality, Clark said, is “part of its problem as art goes to multimedia, using all sorts of things.” In other words, while craft is reaching toward art, art is reaching toward craft — toward an acceptance of all sorts of materials as viable raw material for the making of fine art.

And craft’s stress on physicality, Clark said, is “part of its problem as art goes to multimedia, using all sorts of things.” In other words, while craft is reaching toward art, art is reaching toward craft — toward an acceptance of all sorts of materials as viable raw material for the making of fine art.

Then again, he says, fine art’s embrace of traditional craft materials has more to do with “postmodernism’s promiscuity” — hardly a marriage of minds. And, he pointed out, in the mid-20th century fine art underwent a more than equal and opposite reaction, “away from craft-based values” and toward conceptualism — a conspicuously idea-driven form of art (even if the ideas are sometimes half-baked) that gets big media play even as it often rejects the entire concept of craftsmanship as old-fashioned and irrelevant. No wonder crafters feel a little loss of self-esteem.

There’s truth in a lot of this. I have no doubt that some practioners of craft have pushed to join the fine-art world for a variety of reasons, from self-doubt to the desire for self-sufficiency. (Some Sunday water colorists insist on calling themselves fine artists, too. So, for that matter, does Thomas Kinkade, Painter of Light.) And I have no doubt that some artists/craftspeople/designers have let the art world’s critical machinery set their agendas, rather than the other way around. Life, and people, are like that.

Thursday night’s delicate evisceration was all stimulating and quite a lot of fun, if not always crystal clear: These are confusing waters, even if you have a good depth chart. Clark tossed out a lot of provocative, quotable stuff, including this line on the craft scene’s incestuousness: “Craft is just one cousin away from being a cyclops.”

In one of his major points, he argued that craft should form an alliance not with fine art but with the applied arts — with design: “This is the happy marriage, not the stalking of art.” Craft and design, he said, share a democratic impulse and an appreciation for the finely made everyday thing. In New York, he pointed out, the Gagosian Gallery, a leading fine art venue, exhibited furniture by the star designer Marc Newson and racked up $50 million in sales. And it didn’t present it as fine art. “Larry Gagosian said design didn’t need art to give it veracity,” Clark said. “Craft should say the same.”

Pleasing the Portland crowd mightily, he said that the country’s craft epicenter — by which he meant the American Craft Council — should get out of New York, where it always plays poor cousin to the glamorous fine-art scene, and move to a smaller city where it could be a star on its own. Someplace with half a million people, he suggested, and a big creative culture, and a name that starts with “P.” No one seemed to consider he might be talking about Pittsburgh. Maybe moving was on his mind. After many years with major galleries in Los Angeles and New York, and a regular international reach, he and his partner Mark del Vecchio have moved to Santa Fe and turned their business into a virtual gallery. And his son, Clark says, has recently moved to Portland, so he plans to visit a lot.

Pleasing the Portland crowd mightily, he said that the country’s craft epicenter — by which he meant the American Craft Council — should get out of New York, where it always plays poor cousin to the glamorous fine-art scene, and move to a smaller city where it could be a star on its own. Someplace with half a million people, he suggested, and a big creative culture, and a name that starts with “P.” No one seemed to consider he might be talking about Pittsburgh. Maybe moving was on his mind. After many years with major galleries in Los Angeles and New York, and a regular international reach, he and his partner Mark del Vecchio have moved to Santa Fe and turned their business into a virtual gallery. And his son, Clark says, has recently moved to Portland, so he plans to visit a lot.

Still, the question remains: What do we mean when we say “craft”? Maybe it’s a little like U.S. Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart‘s 1964 dictum on pornography: “I know it when I see it.” The borders are fuzzy, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. One man in the audience last night asked Clark whether we were using “craft” as a noun when we should be using it as a verb. Maybe so.

Either way, there’s something physical about the thing. “Craft is at its best when it is dealing with sensuality,” Clark said. “… (I)t grabs you by the throat and just thrills you.”

Either way, there’s something physical about the thing. “Craft is at its best when it is dealing with sensuality,” Clark said. “… (I)t grabs you by the throat and just thrills you.”

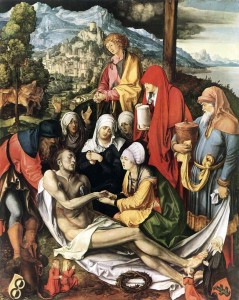

I’ll buy that. But I’ll say the same thing about fine art, too: Unless it grabs you and shakes you and moves your universe just a little bit, it isn’t great art. A Rembrandt portrait. A Christo fence. The amazing technique of a Kathe Kollwitz or an Albrecht Durer. Hans Holbein the Younger’s jaw-dropping Darmstadt or Meyer Madonna, the centerpiece of the Portland Art Museum‘s 2005-06 Hesse exhibition. These pieces ravish you. Then you study them, look for their depths, note their style and context and structure and technique. Then, for good measure, you let them ravish you again. And part of the ravishment comes from their superb craftsmanship.

So maybe the more interesting question is, What is the relationship between art and craft? Does art require craft? If not, has the art world suffered for its loss? Clark says fine art doesn’t need craft. You can make great art without craft, he said, but you can’t make great craft without great skill. This is a far more significant question than many people in the art world will admit. For all of its history, from cave paintings on, art and craftsmanship have been intertwined. At what cost are they separated, if indeed they are? (Of course, you can have fine craft in the service of inert art: A lot of gallery walls are covered with well-shaped dead butterflies. And we all know works of folk or outsider art that move us immensely — but maybe they do so with their own, singular, invented craftsmanship that unleashes their power.)

I’m not so sure, finally, that the differences among fine art and craft and design are all that important, so long as that emotional and intellectual ravishment are there (and they will be there, of course, to varying degrees). To me, the great idea of craft is craftsmanship — that in a finely crafted piece is a beauty, a seduction, an astonishment, an energetic serenity that is sufficient to itself.

Then, is a gorgeous Helen Frankenthaler, for instance, also craft? Well, you don’t touch it. Do you need to touch it for it to be craft? It’s a puzzle. Is there a difference between “craft” and “well-crafted”?

Is part of craft’s worth:

a) its singularity, which one also says about most of fine art (though not prints);

b) the time that it takes an individual crafter to make a particular piece? Is worth a matter of the sweat of the crafter’s brow?

On Thursday night, Clark quoted critic Clement Greenberg, in a 1979 talk to a craft group. “You strike me as a group that is more concerned with opinion than achievement,” Greenberg said.

If we can reverse that in the world of craft, Clark added, we can return to good shape.

By any word, I’ll add, that we choose.