The place to be in Portland Tuesday night was the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall, where the legendary Martha Graham Dance Company was performing in town for the first time since 2004. As if that weren’t draw enough, the program provided the world premiere of Portland choreographer Josie Moseley‘s “Inherit,” a solo for Graham dancer Samuel Pott. Moseley’s piece was underwritten by White Bird, which presented the Graham company as part of its Portland dance season. Catherine Thomas’s review for The Oregonian is here. Art Scatter’s chief correspondent and resident dance critic, Martha Ullman West, was also on the spot and files this report.

*

By Martha Ullman West

Ask a male modern dancer about Martha Graham technique and you’ll likely get a shake of the head, a roll of the eyes, and a lecture on how her pelvis-centered movement is difficult to impossible for a man’s body to do.

This is definitely true of Lamentation, the gut-wrenching, writhing, keening solo Graham made on her own body in 1930, in which she absorbed and expressed all the griefs of a world as troubled as our own, at the same time providing the kind of catharsis the ancient Greeks found in the tragedies of Sophocles, Euripides and Aeschylus.  It’s no accident she later made dances based on Oedipus Rex (Night Journey) Medea (Cave of the Heart) and Agamemnon (the monumental evening-length Clytemnestra) all of them from the woman’s point of view.

This is definitely true of Lamentation, the gut-wrenching, writhing, keening solo Graham made on her own body in 1930, in which she absorbed and expressed all the griefs of a world as troubled as our own, at the same time providing the kind of catharsis the ancient Greeks found in the tragedies of Sophocles, Euripides and Aeschylus. Â It’s no accident she later made dances based on Oedipus Rex (Night Journey) Medea (Cave of the Heart) and Agamemnon (the monumental evening-length Clytemnestra) all of them from the woman’s point of view.

Lamentation is the centerpiece of the Martha Graham Company’s current road show: We saw it twice at the Schnitz on Tuesday night, first performed with smooth elegance by Carrie Ellmore-Tallitsch, her costume — originally a tube of knitted fabric as much a part of the solo as the dancer’s body — perked up with a red leotard underneath it.

Then, post intermission, to introduce the Lamentation Variations we saw Martha herself, on film, gnarled feet rooted to the floor, her seated body arching in a seamless cry. Let it be said that this 80-year-old solo of Graham’s is so emblematic of that period of modern dance that the editors of the International Dictionary of Modern Dance chose it for the book’s cover.

Graham company Artistic Director Janet Eilber, charged with keeping the company afloat and the repertory alive when she took over in 2005, used it in 2007 as an updating tool, if you will, to commemorate the anniversary of 9/11 by asking some of today’s choreographers to make work reacting to the film. This project, according to the program, was so successful with audiences that she kept it going, and Portland choreographer Josie Moseley was commissioned by White Bird to make her own variation on it.

Her take received its world premiere on Tuesday night, and I thought it the best and the boldest of the three, never mind one of the finest dances Moseley has made. (The other two, respectively by Larry Keigwin and Bulareyaung Pagarlava, captured neither my attention nor my imagination, though I don’t question their craft.)

For Moseley, trained in what we now refer to as traditional modern technique, and thus knowing well how difficult the Graham technique is for men, chose to make a solo on the large, powerful body of company dancer Samuel Pott, tailoring the space-devouring lyrical movement to his long legs, with nary a pelvic contraction to be seen.

I wondered more than a bit what this pensive, tristesse-laden solo had to do with the extravagant grief expressed in the original until I spoke about it with my friend Carol Shults, a former dancer who has taken classes in Graham technique, who astutely pointed out that Moseley was reacting to Graham’s woman-centeredness by capitalizing on the talents and body of this wonderful male dancer. The music she chose, by jazz composer Joshua Redman, helped of course to set the tone.

It seems to me that Moseley has made a solo as representative of today’s zeitgeist as the original Lamentation was of Graham’s. This man is grieving, but he’s not throwing around his body — he is, if you will, cool, controlled. Men in this culture don’t go in for extravagant grief, not in art, not in life, which doesn’t mean they don’t feel it. And as a culture, in part due to technology, we are increasingly distanced from our own deeds and the tragedies they cause. Unmanned stealth missiles used in Afghanistan come to mind, and we don’t see the results of that use on the evening news, either.

Has Graham’s day come and passed on with her? One might think so from the rest of this program, which was painfully educational, showing film of DenisShawn, where Graham got her early training, augmented with a live performance of a Ruth St. Denis solo, followed by interesting excerpts from mid-thirties political works Steps in the Street and Prelude to Action, nicely executed by the company.

The closer was Mirthless Martha’s (as accompanist, composer, mentor and lover Louis Horst called her) last piece, Maple Leaf Rag, choreographed when she was 90. It’s self-parody to some degree, as Graham no doubt intended, but when I saw it the first time, I think in 2002, it wasn’t cute and it wasn’t played for laughs, as it was on Tuesday night, so it was a lot funnier and much less trivial.

I’m fearful that from the best of intentions, not to mention lack of funds, we are in fact going to lose Graham’s work, and I don’t think her day has passed. Cave of the Heart, performed when the company was last in Portland in 2004, provided for me the same release Medea gave the ancient Greeks, and when Judith Anderson performed the title role, 20th century America audiences as well. Appalachian Spring, also on that program, resonates with Western audiences as Rodeo never can.

Those works, with their Noguchi set pieces, can be expensive to tour. But the 1935 Frontier, for example, Graham’s first collaboration with the Japanese-American sculptor, is as much about the women who settled the West as any pioneer woman’s diary. It’s a spare lovely solo performed in a space defined by two pieces of rope and a wooden fence.

These works, and many others, don’t need updating. They have the universality and relevance of classics, and I was sorry that the many children in the audience on Tuesday night didn’t, in fact, get to see Graham’s best work.

*

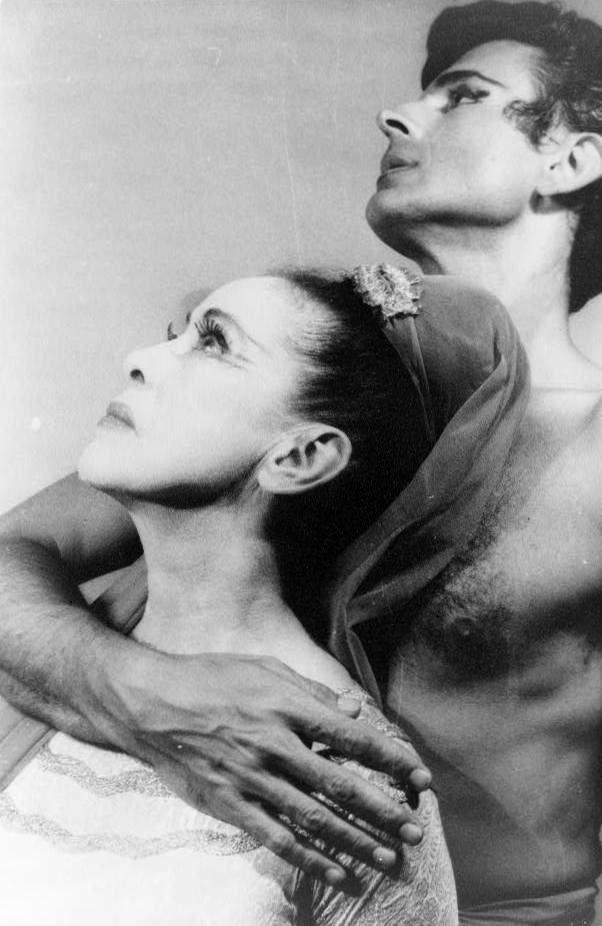

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

- Josie Moseley teaching at the School of Oregon Ballet Theatre. Greg Bond/Oregon Art Beat/2010. Courtesy Oregon Public Broadcasting.

- Portrait of Martha Graham and Bertram Ross, June 27, 1961. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Van Vechten Collection. Photo: Carl Van Vechten (1880–1964). Wikimedia Commons.