“Did you notice how the first lady soloist started dancing just with her hands?”

Intermission had just begun Saturday night at Oregon Ballet Theatre‘s season-opening performance, which had so far consisted of the company premiere of George Balanchine’s green dream of a dance, Emeralds. Mrs. Scatter had scarpered to the coast for one of her intermittent weekends of popping corks and doing crafty stuff with her girlfriends, and Mr. Scatter was in the company of the Small Large Smelly Boy, two weeks shy of his twelfth birthday and taking in his first non-Nutcracker ballet.

“No, Dad,” the SLSB replied patiently. “It was her whole arms.”

So it was.

Those arms belonged to the highly talented Yuka Iino, the fleet princess in this picture-book of a ballet to Alison Roper’s imperial queen.

Premiered in 1967 and seeming older than that (this is definitely a pre-Beatles universe onstage) Balanchine’s ballet is a visual stunner: Karinska’s glittering emerald costumes; the spare vivid set with its falling sweep of white drapery and its lone elegant chandelier high above the stage; the astonishing lighting (originally by Ronald Bates, executed here by OBT’s masterful designer Michael Mazzola) that reminds me somehow of C.S. Lewis’s Narnia series, with its conceit that there are old worlds and new worlds, and that in the new ones everything is brighter, more vivid, more cleanly outlined, and the air seems alive.

But the SLSB, freshly showered for the occasion, isn’t looking at the set. He’s looking at feet. This boy is an observer (and, I think, more a classicist than a postmodernist), and he’s captivated by something that’s captivated millions of people for almost two hundred years: toe work.

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!”

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!”

“Yes,” I replied. “That’s called dancing en pointe. It’s very hard. You have to practice for years and years. Even professional dancers keep practicing it, all the time. Dancers are athletes, did you know that? They have to be as athletic as anybody in a sport, plus they have to be artists.”

“How do they know what to do?”

“Well, the dancemaker, the choreographer, decides on how they’ll move to the music. There are five basic positions that your feet and legs can take, and then there’s lots of variations and different ways you can combine them. But it all starts with those five positions you need to learn. And you work on those all the time.”

I was afraid the SLSB might be bored by Emeralds. It’s hardly the cutting edge of contemporary ballet, after all, and although I love Gabriel Faure’s music, it can be deep and reserved. Perkiness is not its game.

I shouldn’t have worried. My son’s attention was perfectly focused through this long dance, absorbing it, homing in on particulars. He caught the importance of the shoes in absorbing the impact of the weight and pressure on those elevated feet. (Later, watching Dennis Spaight’s fluid and sassy Ellington Suite, he was also impressed that the dancers can dance in high heels.)

The second act of this expansive evening of dance consisted of 10 shorter pieces, in whole or in excerpt, from the company’s history — including one, a scene from The Sleeping Beauty, performed by the young dancers of the company school. This is OBT’s twentieth anniversary season, and it kicked off with a celebration of the company’s past, although with a gaping hole: For reasons that I don’t understand (I know he was asked) the program includes no dances by James Canfield, artistic director for the company’s first fourteen years.

It was terrific, though, to see the inclusion of two pieces by the late Spaight, OBT’s original resident choreographer: Ellington Suite and the lovely Gloria, to a score by Antonio Vivaldi. Spaight’s sinuous, quick, circling approach to balletic motion is still captivating, and I hope these dances become firmly entrenched in the company’s repertory.

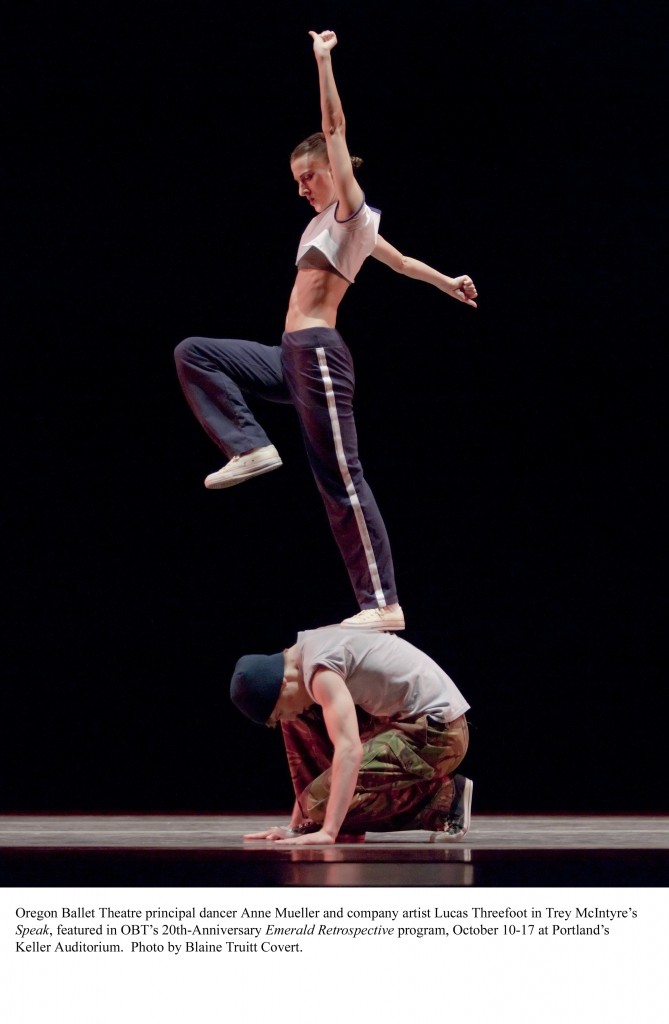

I much prefer current artistic director Christopher Stowell’s approach to ballet to Canfield’s, but a shot of Canfield-style pop-culture energy now and again wouldn’t be a bad thing, as the revival of Trey McIntyre’s 1998 piece Speak reminded me. I don’t think I’ve seen it since the company took it to the Joyce Theatre in New York the following year, and here was Anne Mueller, who danced it then, dancing it again, this time with the rising young corps member Lucas Threefoot. Set to the Bloodhound Gang’s sardonic jazzy hip-hop song Shut Up (“I don’t give a damn that you don’t like me/ cuz I don’t like you/ cuz you’re not like me…”) McIntyre’s dance manages to capture an edge of urban danger and lightly mock it at the same time.

“It’s hard to follow the stories sometimes,” the SLSB commented.

“Well, sometimes you don’t really need stories. The dance tells you its story through the music and the way it moves. You feel it with your eyes and your mind and your heart, and that’s really the story. Does that make sense?”

He nodded. He understood all that. “But still it might be better to give a little bit of story,” he said.

Stowell’s charming version of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, to Felix Mendelssohn’s wonderful score, flew by, a fairy rapture with Iino and Chauncey Parsons as Titania and Oberon, and a nimble, sprightly Steven Houser as Puck.

“I knew they were telling Puck to go do something,” the SLSB said, “but I wasn’t sure what part of the story it was.”

“It’d be easier to tell if they were doing the whole ballet.”

He liked it nonetheless, and also fell for the show closer, Stowell’s brightly comic Eyes on You, to a delightfully brassy recording (I wish I could tell you whose it was) of several Cole Porter tunes.

“Did you have a favorite dance?” I asked.

“The one where they wore the red-wine shirts,” my son replied.

That was, if I figured it out right, Yuri Possokhov’s La Valse, danced superbly on opening night by Gavin Larsen and Artur Sultanov. And I realized that the SLSB had picked out the only piece danced to live accompaniment — in this case, the dual pianos of Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, playing Maurice Ravel’s Piano Concerto in G Major.

The loss for financial reasons of the ballet orchestra this season is a giant setback — recorded music just doesn’t supply the magic of the moment, the lightning interplay of dancers and musicians that gives a ballet the visceral impact of right here right now — and I realized that I had spent the first several minutes of Emeralds disappointed, keenly feeling the loss of the orchestral dimension, until Iino’s arrival with her hands and feet helped me slip into the reality of what was there on stage. Better to eat the peach than bemoan the lack of nectarine. And on this lovely evening, easy to forget the backstage troubles that beset this artistically accomplished company.

Like so many traditional art forms, ballet spends a lot of time worrying about its future. But maybe Doomsday hasn’t arrived.

“Would you like to see another ballet sometime?” I asked as we walked through the brisk fall air to our car.

“What one will they be doing?”

In Small Large Smelly Boy language, I believe that was a “yes.”