Like so many great art forms, dance is a series of interlinked relationships and memories, a tradition that continually redefines and reinvents itself. It lives in the past, and the present, and the future, and its story is written in the memories and associations of open-hearted observers as well as the muscles of dancers and the patterns in choreographers’ minds.

Dance writer Martha Ullman West, one of our best observers, took in last Friday’s Dance United, and for her it was like biting into a madeleine: The reminiscences and connections just began to flow. Somehow, no matter how far-flung, they all looped back to Oregon Ballet Theatre, its history and successes, and this extraordinary event to keep the company alive and vital.

Here is the link to Martha’s review in The Oregonian of the performance. And here, below, is her more personal report on what it all meant:

———————————————————————-

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Dancers came from Texas, Utah, Massachusetts, Canada, Washington state, California, Chicago, Idaho, and that other geographical location, in New York called Downtown, here designated as Portland’s modern and contemporary dance community.

The gifts they brought were generous: their talent and their time. And they were welcomed to Keller Auditorium with the same enthusiasm as Obama’s supporters do and did, reaching into their wallets with many relatively small donations to keep Oregon Ballet Theatre alive. On Tuesday, OBT had in hand $720,000 of the $750,000 it needs to make up THIS season’s deficit.

I’ve been watching dance in Portland and elsewhere for more decades that I wish to reveal, and professionally since 1979, when I wrote an essay on postmodern dance in New York for Dance Magazine. In so many ways, this gala triggered some Proustian moments, also making me think of all the ways that dance and dancers are connected to each other.

Linda Austin’s thoroughly postmodern “anybody-can-dance, any-movement-on-stage-is-valid” Boris & Natasha Dancers (on catnip) took me back to New York’s SoHo and a performance created by Karole Armitage consisting of a group of dancers on their hands and knees, painting stripes on the floor, in humorless silence. They were not skilled at either painting or dancing, but it was the same democratic approach to the art form as Austin’s new dance, which featured such pillars of the Portland community as two Bragdons (Peter and David), Scott Bricker, James Harrison and Peter Ames Carlin galumphing across the stage, one of them wearing red sneakers that I wondered if he’d borrowed from White Bird’s Paul King. (Armitage, you may remember, also made work on OBT’s dancers on James Canfield’s watch.)

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

And I thought about Mark Goldweber, ballet master at OBT under Canfield, then for some years at the Joffrey, and now at Ballet West. (He gave the only authentic performance in Robert Altman’s dance film The Company, in my view.) I wondered what Mark thinks about the way Adam Sklute, now Ballet West’s artistic director, staged this version of the White Swan pas de deux.

When I encountered this ballet’s real-life Prince Siegfried, Christopher Ruud, at OBT’s studios earlier in the week, I spoke with him about his father, who had helped Todd Bolender at Kansas City Ballet (Bolender is the subject of a book I’m working on). Ruud told me he had staged one of his father’s pieces on the company several years ago.

Continue reading Martha Ullman West on Dance United: a personal take →

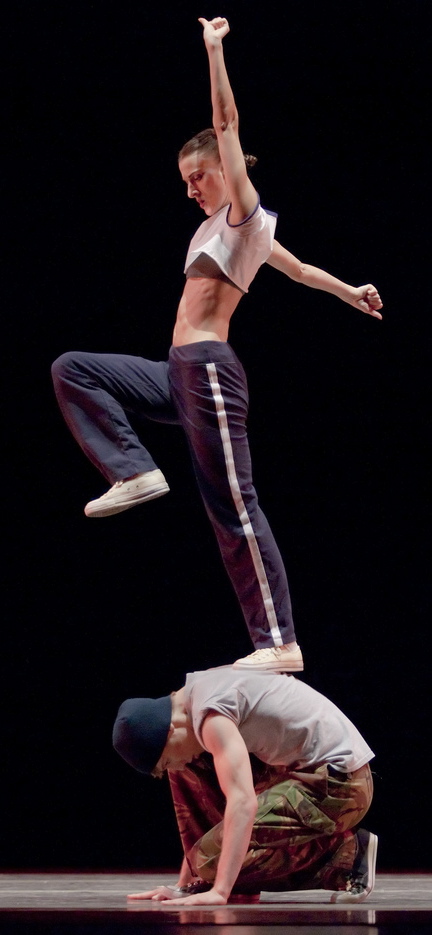

Anne Mueller in Eyes on You. Photo: Blaine Truitt Covert

Anne Mueller in Eyes on You. Photo: Blaine Truitt Covert When George Balanchine created Square Dance for New York City Ballet in 1957, he must have done it at least partly just for the fun of it. What a mashup! — the measured musical courtliness of two Baroque master composers, a stage filled with neoclassically trained ballet dancers, a small Baroque-style orchestra about the size and sonic configuration of an acoustic hillbilly band, and off in the corner, resplendent in Western shirt, bolo tie and cowboy hat, a 20th century American square-dance caller shouting out the do-si-do’s. It took a brilliant creative leap, on a much higher level than the whimsical substituting of a few “w”s for “v”s, to make these cross-century connections, and to make them seem so obvious after the fact: the balanced regularity of Baroque music and country-dance music; virtuoso turns on the 18th century violin and the 20th century fiddle; the stylized courtship patterns in both Baroque and modern country dance; the easy back-and-forth between high and popular art; the backward glance, from the modern ballet stage, to the more rudimentary yet charming forms of the art in Corelli’s and Vivaldi’s times. The incongruities work because, underneath, they really aren’t incongruous at all.

When George Balanchine created Square Dance for New York City Ballet in 1957, he must have done it at least partly just for the fun of it. What a mashup! — the measured musical courtliness of two Baroque master composers, a stage filled with neoclassically trained ballet dancers, a small Baroque-style orchestra about the size and sonic configuration of an acoustic hillbilly band, and off in the corner, resplendent in Western shirt, bolo tie and cowboy hat, a 20th century American square-dance caller shouting out the do-si-do’s. It took a brilliant creative leap, on a much higher level than the whimsical substituting of a few “w”s for “v”s, to make these cross-century connections, and to make them seem so obvious after the fact: the balanced regularity of Baroque music and country-dance music; virtuoso turns on the 18th century violin and the 20th century fiddle; the stylized courtship patterns in both Baroque and modern country dance; the easy back-and-forth between high and popular art; the backward glance, from the modern ballet stage, to the more rudimentary yet charming forms of the art in Corelli’s and Vivaldi’s times. The incongruities work because, underneath, they really aren’t incongruous at all.

The company also announced that Mueller, who has been preparing for her post-dancing career for several years, will remain at OBT as its artistic coordinator, following the behind-the-scenes lead of another fine dancer, Gavin Larsen, who retired from performing last year and joined the OBT School’s faculty.

The company also announced that Mueller, who has been preparing for her post-dancing career for several years, will remain at OBT as its artistic coordinator, following the behind-the-scenes lead of another fine dancer, Gavin Larsen, who retired from performing last year and joined the OBT School’s faculty.

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!”

“How do they dance up on their toes like that?” he asked. “Do they have to work a lot to do it? That must be hard!” Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans. The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

God knows Stravinsky’s 1912 Sacre du Printemps, played brilliantly here in its two-piano version by Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, is structured. Its lyrical beginning builds to a pounding crescendo in music that is still startling for its highly stylized brutality.

God knows Stravinsky’s 1912 Sacre du Printemps, played brilliantly here in its two-piano version by Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, is structured. Its lyrical beginning builds to a pounding crescendo in music that is still startling for its highly stylized brutality.