“I’ve never been very interested in film,” Philip Glass said one morning this week at a long table set up in a rehearsal hall in the Portland Opera studios. “I don’t go to movies a lot.”

An odd confession from Glass, the 72-year-old composer who was in town for several days in conjunction with Friday night’s opening of the West Coast premiere of his 1993 opera Orphee at Portland Opera.

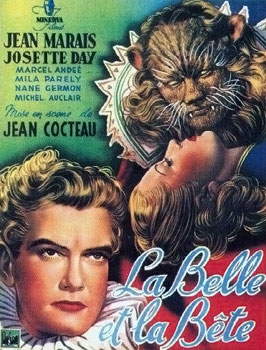

Orphee is, after all, one of a trilogy of operas that Glass has written based on the transcendent movies of Jean Cocteau (the others are La Belle et la Bete and Les Enfants Terribles).

And in a time when classical performers (Yo Yo Ma, Luciano Pavarotti, Andrea Bocelli) achieve celebrity but composers ordinarily don’t, Glass has become famous partly because of his forays into film, beginning with the hallucinatory Koyaanisqatsi in 1982.

Still, what he said made sense, especially when you consider the ways that he’s interacted with film — he’s hardly Hollywood-mainstreamed it — and the sentence he added immediately after his confession: “And yet film is an important aspect of the collaborative arts.”

Collaboration, he said, is one of the great attractions of the film world: It’s filled with extremely talented artists working toward a goal. The technology is amazing. And of course, compared to any of the performing arts, movies are seen: “The reach of film is extraordinary.”

How extraordinary? Glass recalled a story about the day Godfrey Reggio, the director of Koyaanisqatsi, called to tell him their movie was going to be shown on PBS:

“I said, ‘What’s that mean?’

“He said, ‘It means 6 million people will see it that night.’

“I practically fainted. That is not a number that comes into my work very often.”

As it turns out, Reggio’s guess of 6 million viewers was off the mark. Twenty million tuned in.

And that’s how a composer becomes famous, minimalism or maximalism or any other ism aside. Who outside of the pop world is even better-known than Glass as a composer? John Williams, composer for the Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Superman and first three Harry Potter movies.

So. The movies, yes. Glass noted that he did a little work on film crews to pick up extra money when he was a young man living in Paris, and even acted — pretty badly, he said wryly — in a few bit parts.

But he noticed something about film: “It was not an interpretive art form, it was a definitive art form.”

By that he meant, once a film is finished it’s frozen. That’s its form forever and ever, world without end, amen, amen. You can remake with new stars, but then it’s a new work. You can even do virtual scene-for-scene homages like Werner Herzog’s ravishing remake of F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu or Gus Van Sant’s frame-for-frame re-do of Psycho, which had all of Hollywood scratching its collective head. But those, too, become their own discrete objects.

A play or a symphony or an opera, on the other hand, is an elusive, transformational thing, taking on new shapes and layers of meaning with each successive performance: The idea of Carmen today, after thousands of performances, is somehow different from anything Bizet imagined, Glass suggested.

“And then,” he said, “it occurred to me that maybe I could look at film in a different way.”

Glass wanted to explore the difference between something that was recorded and something that is live.

“How can I combine live performance with film? That was the question I asked myself, and the answer to that question turned out to be my three Cocteau operas.”

He had seen the Cocteau movies as a teenager in Chicago when they were new, and like so many people he was swept up by them: They became part of the reason that he moved to France for a time. They stayed with him, and many years later became the basis for a kind of experiment in the enlivening of film.

In La Belle et la Bete Glass made a movie-opera, screening the film with its Georges Auric soundtrack stripped out while the singers and musicians performed Glass’s new score on platforms below.

In Orphee the singer-actors perform on stage as is ordinary in an opera, but the libretto is straight from the movie. (Because it uses the structure of Cocteau’s film, Glass’s Orphee is relatively short, but it’s still 20 minutes longer than the movie: “Simply, it takes longer to sing than to speak.”)

In Les Enfants Terribles Glass transformed the movie into a dance opera, working with choreographer Susan Marshall and placing both singers and dancers on stage.

It’s tempting to say that the Cocteau trilogy is Glass’s revenge on the movie industry, especially after listening to him talk about his frustrations with the Hollywood system of assembling a film.

“The reality is that the film music belongs to the director, and the opera music belongs to the conductor,” he said, noting that Errol Morris and other directors he’s worked with will slice his music up and rearrange it to fit the flow of the film.

He followed up during a lecture/chat Tuesday night in a Portland Art Museum ballroom, commenting on how rarely he’s been allowed to work organically on a film project, getting to know the project from the beginning and writing as it goes along. Instead, film music is almost always composed in a quick burst after everything else is almost done, so that it becomes essentially illustrative.

But as tempting as the idea of revenge is, it also seems not quite right. For one thing, Glass gets along well with Reggio, Morris, Paul Schrader, Martin Scorsese and other directors he’s worked with. For another, Glass is a curious fellow. He simply likes to take things apart, examine them, and put them back together in new and different ways. It’s the joy of the tinkerer.

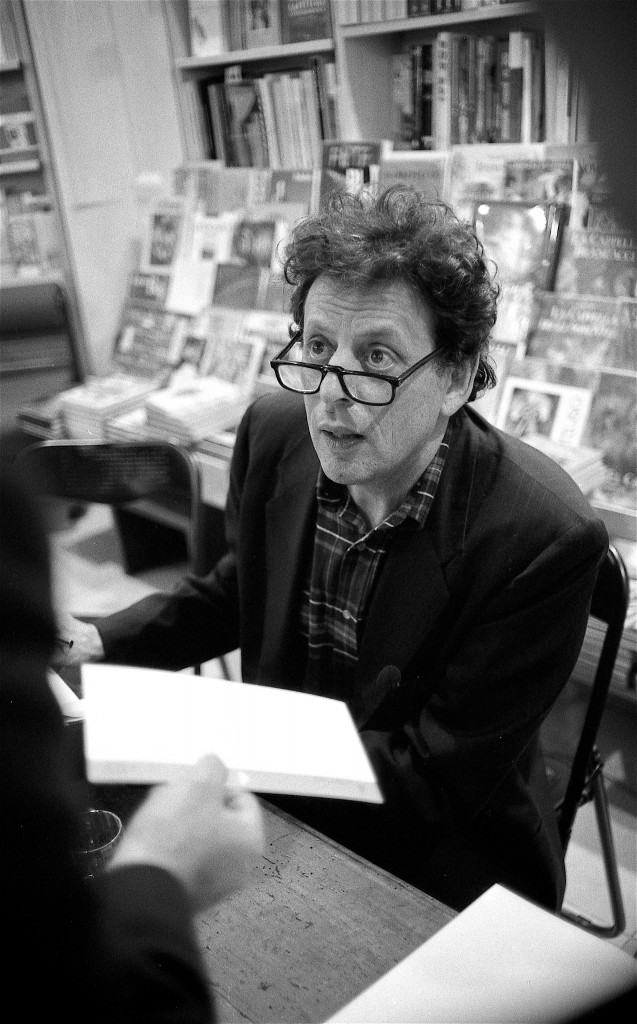

Sitting in a room and talking with him, as I did with a small group of writers Tuesday morning, it’s a little jarring to realize that Glass is 72 years old, an age that should make him an elder statesman, not the outside agitator of the musical establishment that he’s come to be in the popular imagination. (Partly, the public thinks that because it’s an image he likes and encourages).

In a way he seems both. He has astonishing energy to go along with an easy gregariousness and detached warmth: He’s wry and shambling and charming. He seems both young and old — a man of deep experience and constant curiosity.

“That’s an interesting question,” he began his response to almost every query from the audience during his museum talk, and it seemed more than a polite formality: He seemed to genuinely mean it.

Every question is an exploration, and the more he learns the deeper the questions and explorations go. If his responses don’t always entirely focus on the question that was asked — if they tend to wander off and loop around, like his music — that’s OK: The questions are doorways to conjecture.

A sense of wonder — the eagerness of youth, always open to fresh ideas — suffuses his conversation in one direction, while the confidence of experience and accumulated knowledge moves it in another. Forward and backward, at once, like Cocteau’s Orphee and its brash, crucial scene in which Death rewinds time itself. On to new projects, back from minimalism toward his classical roots.

The thing about film, Glass commented, is that “these works lived in a kind of container that they couldn’t break out of.”

With his Cocteau trilogy he broke them out, for better and for worse. And he broke them by combining two things that don’t always go together: popularity and immediacy.

“Some people say they don’t pay attention to the audience,” he said. “I pay a lot of attention.”

And: “Above all, art is a social phenomenon. … Music is what happens when you play. And not just when you play, but when there’s at least one other person in the room.”

———————————————————————————

- PHOTOS, from top:

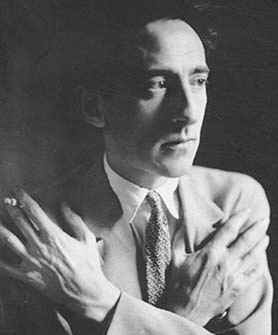

- Jean Cocteau in his 20s. Photographer unknown. Wikimedia Commons.

- The original movie poster for Cocteau’s “La Belle et la Bete,” 1946. Wikimedia Commons.

- Philip Glass in Florence, 1993. Photo: Pasquale Salerno/Wikimedia Commons.

- “Orpheus Leading Eurydice from the Underworld,” Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, 1861. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The myth that Cocteau used as the base for his “Orphee” has been a fount of inspiration for artists for centuries.