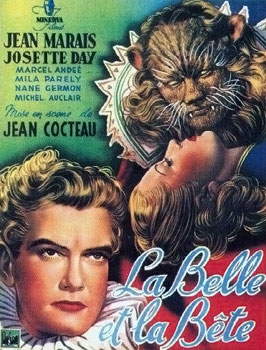

Photo: French poster for Jean Cocteau’s film “Orphee,” the inspiration for Philip Glass’s opera. Wikimedia Commons

8:38 p.m., Intermission: No smoke yet, but lots of mirrors.

One of the coolest things about this opera is the way that it uses the image of the mirror. Very important to Cocteau, and Glass and the set designer, Andrew Lieberman, have picked up on it. The mirror has magical properties. It’s the doorway between worlds, the world of the living and the world of the dead. And that is the journey that Orphee and his put-upon wife, Eurydice, must take. As Death’s chauffeur, the dashing Huertebise (Ryan McPherson) tells Orphee: “You don’t have to understand, only believe.”

The music: Of course you know the Philip Glass joke:

“Knock knock.”

“Who’s there?”

“Knock knock.”

“Who’s there?”

“Knock knock.”

“Who’s there?”

“Philip Glass.”

Well, it’s not true. At least, not in this opera. Sure, he uses a background of repetitions. So did Bach. Listened to any of those organ-grinder Bach numbers lately? Here, that’s just the backdrop for a palette of impressionist sound that somehow seems very French to me — maybe because this is, after all, a French tale, at least in its Cocteau interpretation. I find the music very restrained but opening up at key times, and beautifully sung, although I’d like a little more oomph now and then from some of the voices. That’ll be all balanced out in the recording, and it should sound terrific. Lots of craft in this piece!

*****

PHILIP GLASS BONUS TRACK #3

On Cocteau’s reputation as a flighty man incapable of settling into one discipline:

“My view is that … he wasn’t a dilettante. … He in fact had one idea. His idea was that the transformation of the world comes through magic. And the magic comes through the artist.”

Or, he added, through anyone else who chooses to use it.

*****

I was worried about not having the film itself, because Cocteau is such an amazing poet of the moving picture, and his film of Orphee has some utterly ravishing, untranslatable moments. Glass’s adaptation of La Belle et la Bete uses the film itself — the musicians are below the screen, playing and singing — and there’s a ghostly effect to it. This one’s … different. And not at all in a bad way. The dialogue is word for word from the movie script, but this is a stage drama.

*****

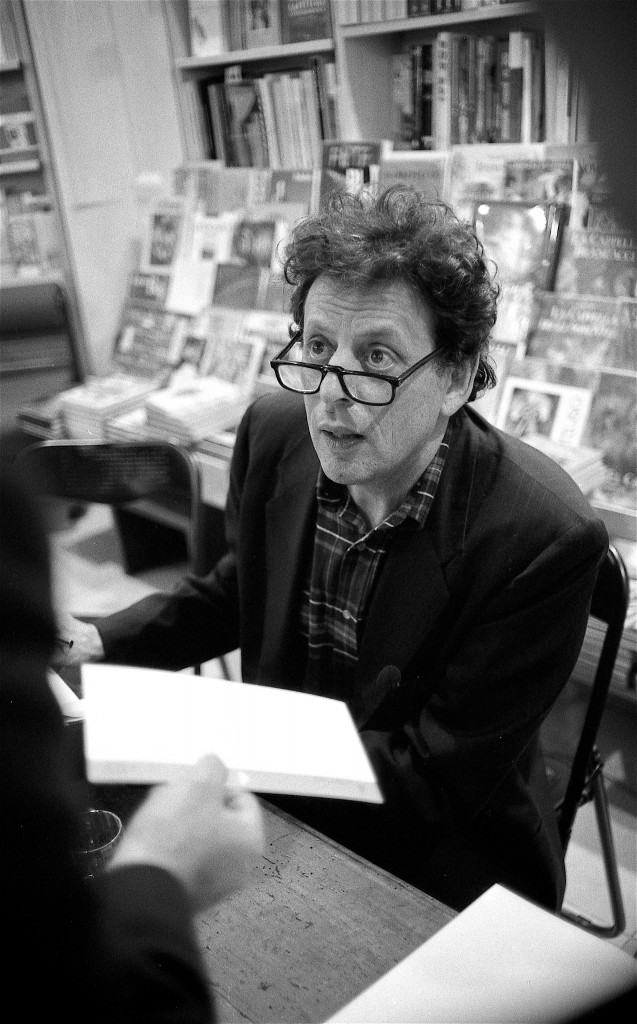

PHILIP GLASS BONUS TRACK #4

Asked whether other composers influenced the music in Orphee, he brought up Gluck’s 1762 opera Orpheus ed Euridice:

“I came across a beautiful melody in that. I tried to write it from memory, and I failed. I ended up writing something that wasn’t like Gluck at all.”

*****