By Bob Hicks

Riches of the City: Portland Collects, the 237-work exhibition of art loaned by 83 of the city’s collectors from their private collections, opens Saturday at the Portland Art Museum, and I reviewed it in this morning’s Oregonian. You can read the review online here, but if you pick up a copy of the morning paper, this is one instance where you’re better off seeing it in print. It’s the cover story of the A&E section, and it includes a lot more pictures than the online edition, including photographer Thomas Boyd’s fine portraits of collectors Jordan Schnitzer, Bonnie Serkin and Chris Rauschenberg with some of their art.

The review stands pretty much on its own, as an overview of what is an overview exhibition. Each of the exhibit’s six areas of concentration makes up its own statement, and each could have been reviewed rigorously on its own, but for most viewers — and for the museum itself — the larger picture is more important.

The review stands pretty much on its own, as an overview of what is an overview exhibition. Each of the exhibit’s six areas of concentration makes up its own statement, and each could have been reviewed rigorously on its own, but for most viewers — and for the museum itself — the larger picture is more important.

So instead of listening to me go into more detail about specific works, I thought you might be interested in reading about how the whole package (the newspaper package, not the museum’s, which took a whole lot longer to negotiate and assemble) came together. The process is both complex and routine, and is a good example of what an amazing structure the modern newspaper is, for all its historical failings and current flailings. Keep in mind, this is an ordinary story that could be planned, not the unexpected emergency that sends journalists into deep scramble mode. Someday someone will write the story of how news of today’s Egyptian crisis reached the world. It’ll read like an unusually fascinating operating manual to a great big complex machine that’s constantly being retooled and reinvented while it’s operating full steam ahead.

I had a fair amount of warning that this story was coming up — much more than journalists often get. But, as is so often the case, I had very little time to turn it around. It began January 24 with an email note from the paper’s D.K. Row asking me if I’d be interested in writing the story. I said yes.

The fly in the ointment was this: The show opens tomorrow, February 5, but Row and his editors wanted to run the story today, February 4. Running on Friday in A&E, it could get much more space for both type and illustrations than if it were to run on Monday. (Because of deadline problems and other priorities, Sunday’s O! section was out of the picture.)

That created a time crunch. A&E is printed on Wednesday evenings, and cover stories generally are finished a week in advance to allow ample time for editing and design. But the museum was still installing the exhibit, and the earliest I could get in to actually see the art hanging on the walls (some of it still wasn’t up) was 3 o’clock Tuesday afternoon. Editors needed the copy to be waiting for them when they got to work Wednesday morning, so the clock was ticking.

This was a sprawling show ranging from Chinese antiquities to English silver to the Hudson River School and contemporary photography and California funk. And I didn’t know what was going to be in it. That’s where Beth Heinrich, the museum’s public relations director, came in. She’d already been in touch with the paper, trying to figure out deadlines and arrange for some of the collectors to come to the museum to pose for photographs. (Photo editor Stephanie Yao Long had been working with Heinrich on that one, which proved complex: In case it didn’t work out, Heinrich, editors and designers were also thinking about a contingency Plan B.)

This was a sprawling show ranging from Chinese antiquities to English silver to the Hudson River School and contemporary photography and California funk. And I didn’t know what was going to be in it. That’s where Beth Heinrich, the museum’s public relations director, came in. She’d already been in touch with the paper, trying to figure out deadlines and arrange for some of the collectors to come to the museum to pose for photographs. (Photo editor Stephanie Yao Long had been working with Heinrich on that one, which proved complex: In case it didn’t work out, Heinrich, editors and designers were also thinking about a contingency Plan B.)

On January 26 Heinrich sent me a copy of the all-important exhibition checklist. With that list of all the works included in the show, I had what I needed to start working. The list gave me a rough sense of what the scope of the exhibition would be, and also allowed me to start doing a little research (God bless Google) on artists and artworks I wasn’t familiar with. Soon after, Heinrich also sent me copies of the brief essays written for the exhibition catalog by the museum’s chief curator, Bruce Guenther; prints and drawings curator Annette Dixon; Asian art curator Maribeth Graybill; and photography curator Julia Dolan. The catalog was still at the printer and not available until today — too late to help with the story — but early copies of the essays gave me a sense of what the curators were thinking when they made their selections.

Meanwhile, space for the review had to be negotiated. Row initially suggested 40 inches. Concerned about time, I said I could probably handle it in 25 to 30. But once I saw the checklist I realized that wasn’t going to work, so I sent another note asking for 35 to 40. Row replied, “Let’s push for 40,” and he did. Page designer Fran Genovese responded with this note: “We can do 40. I will plan for that and adjust down if need be (but I am going to cross my fingers that I don’t need to as I will have very little time on Wednesday to play with things).” Then she added: “Enjoy the exhibit!” So, the plan was in motion: Heinrich would set up the photos, the collectors would arrive for the photo shoots, Thomas Boyd would take the shots, Long would edit them and pass them along to Genovese, who would design the package and lay it out across four and a half pages. All that was missing was the type, which could be stripped into its assigned space as the final piece of the puzzle — after it had first been line-edited and copy-edited.

But before anyone could get the copy, I had to actually see the art. As much research as you can do beforehand, you can’t know your reaction to a work of art until you experience it in the flesh. So a little before 3 on Tuesday afternoon, I arrived at the museum. Heinrich was there to meet me, and we were soon joined by museum director Brian Ferriso, who talked with me for a while about the exhibit, and collecting, and the relationship between museums and collectors. Then Guenther joined us, Ferriso left, and Heinrich, Guenther and I moved into the gallery spaces to see the stuff.

We did a long slow walkthrough, Guenther talking about specific pieces and me asking him about others. None of the didactics — the explanatory wall plaques — were installed yet, so I asked a lot of questions. Even if I thought I knew the answer, I asked. Is that a Donald Judd sculpture? Yes. I took enough notes to feel confident that I’d be able to match pieces against their titles from the checklist. After the walkthrough, Guenther left, and I began to retrace my steps over the exhibition’s two floors, sometimes moving quickly, sometimes taking a little extra time with a piece I wanted to experience a little more fully. The whole time, museum installers were hard at work, getting everything ready. For obvious reasons, the museum requires someone to be on hand in the galleries when a non-employee is going through them, and Heinrich — as she has several times in the past — took up the task, patiently allowing me to wander around like a hound dog exploring new territory, sniffing and examining and picking up the scent. I finally left the museum about a quarter after 5.

We did a long slow walkthrough, Guenther talking about specific pieces and me asking him about others. None of the didactics — the explanatory wall plaques — were installed yet, so I asked a lot of questions. Even if I thought I knew the answer, I asked. Is that a Donald Judd sculpture? Yes. I took enough notes to feel confident that I’d be able to match pieces against their titles from the checklist. After the walkthrough, Guenther left, and I began to retrace my steps over the exhibition’s two floors, sometimes moving quickly, sometimes taking a little extra time with a piece I wanted to experience a little more fully. The whole time, museum installers were hard at work, getting everything ready. For obvious reasons, the museum requires someone to be on hand in the galleries when a non-employee is going through them, and Heinrich — as she has several times in the past — took up the task, patiently allowing me to wander around like a hound dog exploring new territory, sniffing and examining and picking up the scent. I finally left the museum about a quarter after 5.

When I got home I had a note waiting for me from A&E editor DeAnn Welker, asking if I had any headline ideas. I thought a bit, then shot her half a dozen possibilities: She chose the first one. Now everything was ready except the story itself, which at this point didn’t exist.

And before I started writing, I needed a little time to decompress. A quick dinner (no wine, but I made two pots of coffee during the evening) whose contents I can’t remember: My wife kindly cooked, and I quickly ate. The two teen-age boys, cooperating magnificently, disappeared into their rooms. And by 6:30 I was at the computer, wrapped into my own little world. Coffee is, indeed, the wonder drug.

By 12:30 Wednesday morning, I was done. Describing exactly what happened in those six hours is, unfortunately, a little beyond me. There are mechanics I could explain. I could talk about the cross-checkings, the categorizing, the occasional stretches and walks around the house, the stash of little chocolate orange slices that mysteriously shrank. But after more than 40 years of doing this sort of thing, the core of what happens in the writing process I still don’t really understand. I read through the piece, checked spellings and facts, jiggered a word or phrase here and there. At 1:20 a.m. I hit “send,” shut down my computer, and headed to bed, where I read something I can’t remember for a few minutes until the buzz died down and I could go to sleep.

On Wednesday morning the editors and designers picked it up. The story fit. If anything was changed in the copy, I didn’t notice it. And in the wee hours of Friday morning, deliverers across the metropolitan area took a bead on doorsteps and tossed their plastic-wrapped papers to readers who weren’t awake yet. Mission accomplished.

I didn’t talk with any of the collectors, and I didn’t talk with any of the exhibition’s curators besides Guenther. Both would have provided interesting information, and both would have made for good stories. But you can’t do it all. And besides, I only had 40 inches.

*

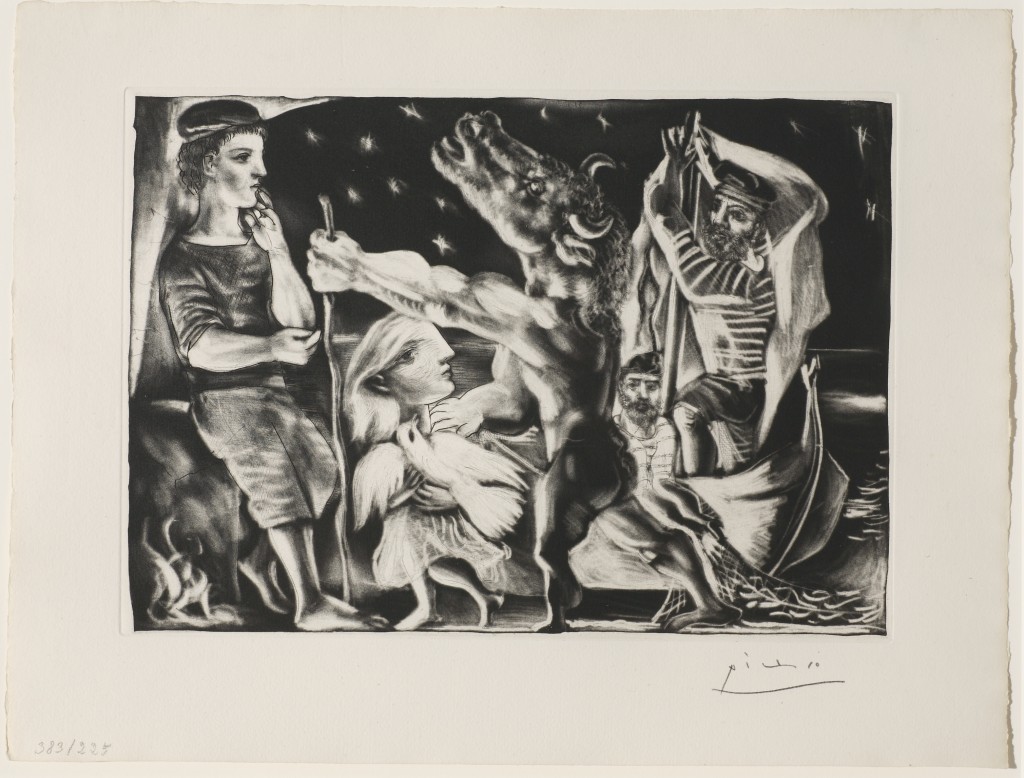

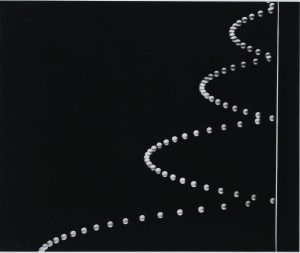

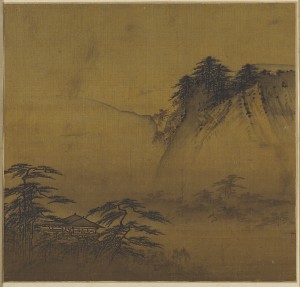

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

- Pablo Picasso, “Blind Minotaur, Guided through a Starry Night by Marie-Therese with a Pigeon),” 1934-35 from the Suite Vollard, 1930-37. Aquatint, drypoint, and engraving with scraping, edition of 250, Anonymous loan.

- Roy DeForest, Forest Hermit, 1990, Acrylic on canvas with artist-carved frame, Collection of Arlene and Harold Schnitzer.

- Morris Louis, “Beta Omicron,” 1960-61, Acrylic on canvas, Collection of Helen Jo and William Whitsell ⌠Morris Louis.

- Berenice Abbott, “Path of a Moving Ball,” c. 1960, Gelatin silver print, printed c. 1982, Collection of James and Susan Winkler.

- Attributed to Xia Gui, “Viewing Pavilion Overlooking Misty Valley,” Southern Song dynasty, late 12th-early 13th century, album leaf, ink and light color on silk, Collection of Andre Stevens.