By Bob Hicks

Someone called Singlet, responding online to the obituary in The Guardian for the novelist and children’s writer Russell Hoban, had this to say: “A few comments that Hoban’s other novels don’t come close to Riddley Walker make me think of what Joseph Heller reportedly said when asked, ‘Why have you never written anything else like Catch-22?’ — ‘Well, nobody else has either.'”

Exactly.

Exactly.

Hoban, the American-born writer who died in his adopted England on Tuesday at age 86, was far from a one-hit wonder. But Riddley Walker, his 1980 novel set in the crude countryside of Kent a couple of millennia after a nuclear apocalypse, is undoubtedly his Catch-22, the novel of astonishing accomplishment and originality that stands as the peak of a fertile and often brilliantly surprising career.

Young Riddley lives in an age of rubble: partly Mad Max free-for-all, partly pre-Roman Celtic drudgery, partly tightly controlled medieval theocracy. What quickens the book, and distinguishes it from the standard run of post-apocalyptic lit, is its language, a wildly inventive yet carefully considered deconstruction and reassembly of contemporary English as it might have devolved and reinvented itself in the centuries after a global disaster. The writing is constantly involving and often hilarious, and once you get the hang of it (reading a couple of pages out loud helps immensely) it makes extraordinary sense. A lot of other writers have made hay by taking liberties with the language and its tangled roots: James Joyce poetically and esoterically; J.R.R. Tolkein allusively and academically. Hoban did it with a literary everyman’s gusto and sly wit.

In Riddley Walker, the wit carries over to Hoban’s invention of incident. As a not-quite anthropologist (like some doctors of jurisprudence, I got the degree but never practiced) I find the book hilarious for the inventive ways in which Hoban’s characters misinterpret the past, coming to conclusions that seem based on the available facts but are utterly and often fantastically wrong. The wordplay is consistently entertaining, as in Hoban’s explanation of the ancient and powerful Puter Leat, masters of the “girt box of knowing and you hook up peopl to it thats what a puter ben.”

And the concept of a menacing religious orthodoxy in which a Punch and Judy puppet show plays a crucial role appeals immensely to a dark and tawdry corner of my soul. For all its caustic view of human motivation and social structures, Riddley Walker also pulses with a coarse and antic optimism: An instinct for individual survival that might overcome even the most perverse of group stupidities is built into Hoban’s view of human possibility.

Some of Hoban’s other novels (I’ve by no means read them all) are also well worth the time. Turtle Diary became a film with a screenplay by Harold Pinter. Pilgermann, which came three years after Riddley Walker, transposes some of its ideas inventively into the crude and violent realities of the European Dark Ages.

Hoban also wrote many delightful children’s books that balanced gentleness, humor, and a realistically subversive sense of the childhood tension between order and anarchy. Over the years he fathered seven kids, so he knew the territory well. A lot of readers swear by The Mouse and His Child, which I haven’t read. But Frances, the willful, lively, not-so-perfect and utterly appealing young badger heroine of such picture-books as Bedtime for Frances, A Baby Sister for Frances and Bread and Jam for Frances, was a bright and funny staple in our household through the raising of three children. As the crafty Frances says in her complex and justifiable if not entirely admirable campaign to make a swap for a much-desired toy tea set, “No backsies.”

Bruce Weber, in his fine obit for the New York Times, cites a passage from Hoban’s 1992 collection The Moment Under the Moment that suggests why, in addition to his dazzling linguistic playfulness, other writers esteem Hoban so highly: “The most that a writer can do – and this is only rarely achieved – is to write in such a way that the reader finds himself in a place where the unwordable happens off the page. Most of the time it doesn’t happen but trying for it is part of being the hunting-and-finding animal one is. This process is what I care about.”

Another online commenter on The Guardian obit, Littlshyninman (if you know Riddley Walker you’ll recognize the name), quotes from Hoban’s barely known book Fremder: “More and more I find that life is a series of disappearances followed usually but not always by reappearances; you disappear from your morning self and reappear as your afternoon self; you disappear from feeling good and reappear feeling bad. And people, even face to face and clasped in each other’s arms, disappear from each other.”

Farewell, Russell Hoban. Yes, you’ve disappeared. But in the imaginations of your readers now and yet to come, you’ll reappear many, many times.

*

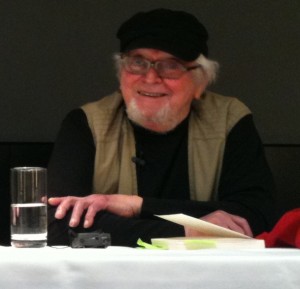

Russell Hoban in November 2010. Photo: Richard Cooper, Wikimedia Commons.