By Bob Hicks

I remember Sergiu Luca in the steamy July heat of a makeshift concert hall at Reed College, sweating with the audience and instrumentalists through a little gem of a summer music festival he’d begun in 1971 called Chamber Music Northwest.

I remember him beaming above the breakwaters at Cascade Head on the Oregon Coast, a glass of good wine in one hand and the other sweeping through space in accompaniment to a robust story.

I remember him beaming above the breakwaters at Cascade Head on the Oregon Coast, a glass of good wine in one hand and the other sweeping through space in accompaniment to a robust story.

I remember him meeting and greeting people at the even littler Cascade Head Music Festival he began in the tiny town of Otis and later moved to Lincoln City after Chamber Music Northwest became too much of a production, smiling and joking with people ranging from local fishermen to high-powered musical figures such as Joan Morris and William Bolcom who’d come to the beach to sing and play with their old friend.

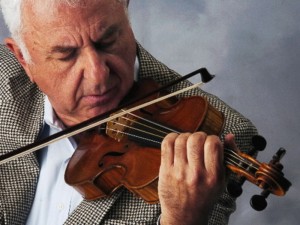

Most of all I remember Luca with a fiddle in his hand — a very old and rare and beautiful fiddle, which he played with the light and grace and airiness of a man who had not just the right but the joyous responsibility to own and play such a wondrous concoction of wood and glue and string. With a violin tucked beneath his chin, Luca created music that was much more than precise and correct. It had swagger and pleasure and verve. If you wanted to call it classical, OK, but you could never call it boring or musty: it was a living, shifting, up-to-the-minute thing.

Sergiu died Monday night in Houston, where he was even better-known than in Oregon. Sarah Rufca has the story on Culture Map Houston. The Oregonian’s David Stabler has this report on Oregon Live, and Allan Kozinn has this obituary in the New York Times. Things Rufca revealed: Luca was born in 1943 in Romania, and began to learn the violin at age 4 from a Gypsy, and made his debut at the Haifa Symphony in Israel when he was 9. He died of bile duct cancer, and there is little doubt that, although he died too young, he lived a rich life and enjoyed pretty much all of it.

Sergiu loved to meet people, loved to talk, loved to eat and drink. Classical musicians in general seem to love good food and wine, which seems like a pretty good reason to take up an instrument, but Luca was a master among masters in the gourmet game. His life was hard work, but it was hard work in the pursuit of pleasure: giving it and receiving it, at a level where the heart met the brain and jump-started all of the senses.

I remember the year he brought a trio of very old pianos to Lincoln City, along with some masterful pianists adept at performing on their range of sound-boxes from post-harpsichord intimate to big and brawny, and along with a swaggering European piano restorer who had brought new life to an instrument that had been buried in a barn under chicken droppings for a century. Best thing that could have happened to it, the master craftsman said with a grin: It saved it from ruin at the hands of ham-fisted restorers who might have “modernized” it and ruined it forever.

And I remember the time Sergiu held out his 300-year-old violin to me and calmly said, “Here, hold it,” which, trembling for fear of dropping it, I did. It seemed lighter than air, a magical handful of nothingness, as evanescent as music itself. I smiled. Sergiu laughed. I handed it back.

Thank you, Mr. Luca. Somewhere, in some elusive part of me, I still hold your violin.