By Bob Hicks

Bless me, reader, for I have sinned.

For 40 years Moses wandered in the wilderness. And for roughly the same amount of time I have stumbled through the landmines of contemporary culture, wearing the sackcloth of the most extreme form of penitent journalist.

I have been a critic.

I have been a critic.

Well, apparently I have. That’s what everyone tells me. Lord knows I’ve denied it over the years. For a long time, when people called me a critic, I’d correct them. “I’m a writer,” I’d gently explain, “and these days I happen to be writing about theater.”

It did no good. No one believed me. And “Writer Who Writes About Theater” doesn’t fit in a byline, anyway.

A few years ago I was chatting with Libby Appel, who at the time was artistic director of the Oregon Shakespeare Festival. “You know, I’ve never really thought of myself as a critic,” I told her.

Libby’s eyebrow arched. (Sometimes eyebrows actually do that.) “Oh, you’re a critic,” she said emphatically.

I like to think she was delivering a description, not an accusation. I like her and respect her, even though I’ve sometimes argued in print with shows she’s directed, and I think the feeling’s been mutual. Still. There was no question in her mind. I was, without doubt, One of Those People. And Those People occupy a curious position in the artistic firmament. “Critics never worry me unless they are right,” Noel Coward once commented. “But that does not often occur.”

Then again, what exactly is right?

The question comes up thanks — indirectly — to Brian Parks, arts editor of the Village Voice, who not so gently eased Deborah Jowitt out the door because Jowitt, one of the deans of American dance writers, was not sufficiently negative in her reviews. Jowitt’s resignation raised a ruckus among artists and critics alike, one of whom, my friend and longtime arts-writing colleague Barry Johnson, posted a particularly incisive response on his blog Arts Dispatch. I stepped in with a brief post essentially directing readers to Barry’s essay. Then another good friend, Marty Hughley, the gracefully splendid current occupant of the theater critic’s desk at The Oregonian, began a provocative discussion at Oregon Live. If you have two cents, it’s worth throwing it in there.

The discussions have been fascinating, at least to those of us in the insular worlds of artmaking and its beloved enemy, arts journalism. If our favorite topic is us — and, let’s face it, that holds true for most human beings — this is the sweet spot in our strike zone. And it seems to come down to the reductive versus the expansive: thumbs up/thumbs down versus the more inquisitively anthropological what’s it all about? As Barry describes it: “Critical engagement means more than a grim argument ‘for’ or ‘against’ an artwork (of whatever sort). It should be a more creative and speculative inquiry than that.”

It’s now time for me to lob my own little grenade into the discussion, so here goes: the word “critic” is a dumb word. (From my perspective, the word “art” is a dumb word, too, but that’s the subject for another essay that may or may not ever get written.) I’d like to make the case for my self-description as simply a writer.

Yes, I’ve been a specialized sort of writer. To begin, I’ve been a journalist, and that designation implies not just a submission to truth (which good novelists, poets and playwrights share) but also to facts (which historians, popular-science writers and political analysts share). Yet given those strictures and structures, the task has been open: I’ve tried to approach it with inquisitiveness, not inquisition. For many years my shorthand description of what a critic/reviewer/arts writer should do has been this: he or she should open windows. By that I mean, the analyst of art ought to be offering readers a fresh perspective, a new way of entering into the discussion that any decent work of art invites. The critic’s role is to show the way through the looking-glass, or the wardrobe, or the periscope, into the strangely alternate world that the artwork inhabits. Each little piece of “criticism” ought to be a small window into a much larger world. And when a person begins to think of his or her writing as a window into something larger, he or she begins to understand that it’s only one out of many possible windows — not the truth, but a truth. The truth as a particular writer in a particular time and place divines it.

And that openness, at least as aspiration, is really what the writerly craft is all about. It’s fair to say that journalists are secondary writers, responding to specific experience — and in the case of arts journalism, responding to someone else’s already crafted response to human experience. But primary or secondary, the impulse is largely the same: to interpret, from one’s own peculiar vantage point, the experience that comes one’s way. It helps infinitely if you can also engage and entertain your readers along the way.

I can’t say that any critics have been more important in my evolution as a writer than other artists have. Jonathan Swift, Henry Fielding, Jane Austen, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Haydn, Henry Purcell, Cary Grant, Gene Kelly, Trisha Brown, Paul Klee, Miles Davis, James Thurber, Leontyne Price, Alan Ayckbourn, Fragonard, George Orwell, Bela Bartok, Billy Shakespeare, Kitty Wells, Antonio Gaudi, Baryshnikov, Kathe Kollwitz, Jean Cocteau, Nina Simone, W.B. Yeats, the Flying Karamazov Brothers have had more direct impact on my thinking than any of my fellow (for lack of a better word) critics, and that’s as it should be. That’s not even mentioning the myriad Pacific Northwest artists of all sorts of stripes who’ve influenced my thinking and my life. Among the writers about art, I’ve been more a Harold Rosenberg sort of guy than a Clement Greenberg sort of guy, because Rosenberg, I think, was less didactic and more provisional — more open to alternate possibilities. I’ve appreciated Jan Kott as an original thinker, Kenneth Tynan as a superb stylist and freewheeling chaser of ideas, Brooks Atkinson as a steady and honest voice. It didn’t make a speck of difference whether you agreed with Pauline Kael, the legendary movie critic for The New Yorker, or even whether she agreed with herself in the course of spinning out one of her extraordinary essays. She was a performance artist in the guise of a critic: there was a time when people were as breathless to read Kael’s latest castigations or effusions as to hear the newest albums from Dylan or the Beatles.

I won’t begin to touch here on the extreme influence that “private” life has on the shaping of any writer: the loves, losses, husbands, wives, children, matters of health and travel and friendship and economics and appetite and political persuasion and temporary or permanent grumpiness and accident. Yet the point is easy to understand. Any writer is the sum of his or her parts, and on rare occasion, with enough serendipity and talent, he or she transcends the total. So are Tynan and Kael critics, or artists, or neither, or both?

No real writer, not even a critic, is a metronome. In a very real sense, what you get when you read a good writer on the arts is the gift of that particular human being. And human beings being what they are, that gift might be splendid but it is also both untrustworthy and erratic: the same gift that friends and artists and even, god forgive them, politicians bestow. So, as in real life, you hook up with one who in some way or another you find congenial, even if the particular congeniality consists of having someone you can reliably be irritated with. Newspaper reviewers are, of course, more public than other members of the species — certainly more so than academic critics, who tend to talk mainly among themselves — and tend to gather, in addition to friendly and open readers, a few angry followers who can verge on the crackpot. Or, because words have consequences that writers often can’t anticipate, who just plain hurt. My onetime colleague Ted Mahar once told me about running into an actress and her young daughter at a grocery store. “This is Mr. Mahar,” the actress told her daughter. “You remember me talking about him. He’s the man who made Mommy cry.” Back in the days when people wrote letters and made phone calls, I was accustomed to coming to work in the morning and finding a long telephone message from the same nasal-voiced reader, who apparently went out of his way to read my columns at 2 or 3 in the morning. His ramblings would begin softly, in a carefully restrained attempt to maintain reason and civility, and over the course of five or six minutes would crescendo into ear-splitting torrents of outrage. What was astonishing was that the meaning was almost entirely sub-literal: I could rarely get what he was saying, only the fervor beneath the words. For a while I would listen to the entire rant, fascinated by its ferocity. Eventually, once I heard that voice, I just hit the delete button and hung up: been there, heard that. For a while I had a reader who was brutally convinced I was an anti-Semite. I had another who was equally convinced I was a tool of the Zionist conspiracy. Both called regularly, and were all but impossible to get off the line. Interestingly, both were active at the same time. And I never understood what set either off. Some loyal haters derided my lack of historical perspective; others ridiculed me for living in the past. Sometimes readers would write or call to point out a mistake, and lo, they were right. Sometimes critics of the critic picked up the phone because they just wanted to talk: they wanted to pursue an idea, or they’d reached different conclusions and wanted a little more information on how I’d reached mine. Those were good calls. Because in my view, a review should never be looked on as the final word, but as the beginning of a conversation. And sometimes, people want to take in the actual experience before they’re ready to begin even a literary chat. One friend, a fellow journalist who is also a fine poet, used to tell me, “I’m seeing (insert name of show) next Saturday. I’ll read your review after that.”

A strange thing about the printed word is that it creates the illusion of authority: a review, once it’s committed to print, becomes a kind of received, or at least perceived, truth. Even historians consider reviews primary sources of information, and of course once a certain amount of time has passed they become as primary as you can get. But they’re not the original event. They are interpretations. Still, newspapers and magazines love the idea of institutional authority, and so a sort of encrustation of viewpoint sets in that most reviewers I’ve known find frustrating. Few reviewers (there are exceptions) feel like God, and fewer yet consider their conjectures the word of God. Yet print, and publications, seem to want to make it so. Once my friend and colleague David Stabler and I traveled to Eugene for the opening of 1,000 Airplanes on the Roof, a contemporary sci-fi opera by playwright David Henry Hwang and composer Philip Glass, with projections by Jerome Sirlin. David disliked the opera, I liked it quite a bit. Immediately after the show we got on the phone to the newspaper and dictated a dual review: he said, I said, he said, I said, he said, I said. We had a great time arguing. Readers loved it. Certain key editors did not. We can’t argue with ourselves in print, we were told. Never do that again.

Sometimes it’s the writers themselves who don’t like to be doubled. On another occasion a different editor decided it would be fun to send me to cover a professional wrestling match, on the theory that the whole thing was theater, anyway, so why not have the theater reviewer write about it? He sent me with the sports guy, who was supposed to write the sports story while I covered the theatrics. The sports guy, a man of mighty ego, was miffed, and I heard about it all night. I was tromping on his territory, and there could be only one ordained voice of God.

Reviewing for a newspaper is like working in the applied arts. You are free to follow your writerly instincts, so long as you apply them to the task at hand. You can’t produce a Dale Chihuly jellyfish when the customer is expecting a decent set of drinking cups. Not only editors, but more importantly, readers have certain expectations. Those expectations help define the acceptable contours of any essay about any kind of art. And readers of different publications have differing expectations. Readers of the New York Daily News have different priorities than readers of the New York Times. No sense fretting about it: it’s just the way it is. I’ve always felt that (a) my “bottom line” on whether a work of art is “good” or “bad” is the least interesting thing I can write about in most stories; and (b) one way or another I’d better address it, anyway, because readers expect it — and they have that right. Newspaper reviewers often face another situation that a lot of other writers don’t usually face: they often write about things that don’t particularly interest them personally. The task can get tricky here. Nobody is interested in everything that falls within a particular discipline. Sometimes the visual arts writer could care less about French academic painting, or the classical music guy can’t stand Gregorian chant, or the pop music writer just doesn’t get Lady Gaga. Those are the times when your talents as a writer are tested. Do you understand where the art’s coming from, even if it doesn’t happen to do anything for you? Can you fairly and perceptively analyze it? Hemingway didn’t have to write about people he found decent even though he’d never want to have a beer with them.

So. Does Deborah Jowitt write too “softly” about dance? To me the question doesn’t make a lot of sense — or it makes sense only if you consider “Is it worth my money?” a more important question than “What’s it all about?” Even then it doesn’t make a lot of sense, because how do you know if it’s going to be worth your money if the writer hasn’t engaged with the subject and given you something besides Thumbs Up or Thumbs Down to go on? Is an ambitious failure less money-worthy than a small success? Is it a failure if it’s simply imperfect? To me, Jowitt has always been a fearless explorer, ready and willing to go into the thickets of the modern and contemporary dance worlds and report back on the things she’s seen. I’ve plucked at random one short paragraph from her recent review of Karol Armitage at the Joyce Theatre, a passage that mentions in two words (“all splendid”) her thumbs-up view of the dancers but spends its time and Jowitt’s considerable skills instead describing the excitement of the moment and the nature of the art itself. It’s a small gem of precisely heated description, and why would you want to sacrifice that to something that is simply didactically prosaic?

With her 1981 ‘Drastic Classicism’ (also on Program A at the Joyce), Armitage embraced punk – perhaps, in part, as a way of smartly deconstructing her own style. In the edited 2009 version shown at the Joyce, the dancers saunter instead of walk, ooze their way into dancing as if exhausted from too much partying, and mess with the drummer and four guitarists who manage the tremendous din of Rhys Chatham’s music. Once galvanized, they fling their legs wantonly, let gestures melt and blur, and stare hotly at the audience. These performers (all splendid) may not even have been born when the piece premiered. They perform the retro bash with a glee that says, ‘Being bad is such a turn-on!’ It’s kind of endearing.

“Only connect!” E.M. Forster exhorted in Howards End. “… Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted … Live in fragments no longer.” That, I’m going to suggest, is the task of all critics, all writers, all humans. The connection of people and ideas is what matters, and it’s what writers, in their odd little eyries, struggle to do. The more surprisingly and engagingly and convincingly they can do it, the better at it — the more thumbs-uppish — they are. I’m going to also suggest that the connections that create communities have something to do with Jowitt’s approach to writing about dance. She holds a particular position in the dance community — she is not a dancer (although she began as one) or a designer or a choreographer, but a chronicler — yet she is very clearly a part of it. Most writers about art grapple with the question of their relationship to artists, and come to varying conclusions. How distant must they be to preserve their integrity? How close should they be to understand what they’re writing about? I am consistently and gratefully aware that without the grace and generosity of artists, I would be at sea. Over my career hundreds of actors, directors, musicians, dancers, writers, painters, sculptors, curators, choreographers have explained their work to me, filled me in on their own enthusiasms and influences, allowed me to watch them in their studios and rehearsal halls, taken the chance that perhaps, if they open up, this sort-of-outsider sort-of-insider might get it right. Writers, like other artists, know that sometimes they have to be cruel: the integrity of the story means someone will be hurt. (And part of being a writer, perhaps the shameful part, is developing the sort of ego that makes you willing to do that.) Dorothy Parker notwithstanding, that doesn’t mean you have to hurt people arbitrarily or capriciously. The artists who have opened their lives and work to me have, in a very real sense, helped create me as a writer. (As a critic, yes, but what I really mean is as a writer.) For that I should set them up for a glib putdown or a cheap laugh? Sure, I’m a sinner. But I’m going to have to say, as I think Deborah Jowitt has said so consistently and eloquently over the years: thumbs down to that.

*

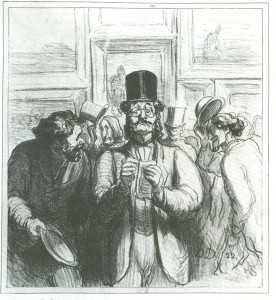

Illustration: Honore Daumier, “The Critic.”