In the past few months Art Scatter’s chief correspondent, Martha Ullman West, has been (as The New Yorker likes to say about its own correspondents) far-flung. We could tell you how much flinging she’s been up to, but it seems more appropriate to let her tell you herself. We will mention, however, that one of her flings was up the freeway to Seattle, where the national Dance Critics Association held its annual meeting and presented her with its Senior Critic’s Award, an honor that recognizes her position in the loftiest echelon of the profession. Congratulations, Martha, once again.

*

By Martha Ullman West

It’s a long time since I’ve made my presence known on Art Scatter (except to comment, lazy me). Since I last posted, on April 10, I’ve seen quite a lot of dancing, a Greek ruin or two or three, Maltese, Sicilian and Spanish museums, the Holy Grail (or not…), a clip aboard ship of the latest royal wedding extravaganza. I also received a prize, for which I had to give a lecture, and that little task made me think about all of the above and more.

Just before I skipped town on April 23, I witnessed Anne Mueller dance ballet for the last time opening night of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s final show of the season, still at the top of her form, showing her range in Trey McIntyre’s funky Speak, Nicolo Fonte’s Left Unsaid, and Christopher Stowell’s Eyes on You. More down the line about the opening ballet in that program, Balanchine’s Square Dance, which I also saw New York City Ballet perform in May.

Earlier in the week, at Da Vinci Middle School’s spring concert, a motley batch of middle school-age boys, seven of them, performed, identifiably, Gregg Bielemeier’s idiosyncratic juxtaposition of small precise movement and space-eating choreography, improvising within the form. At an age when going with the flow ain’t a goin’ to happen, they did just that, and it was lovely to see.

And then I was off on a cruise of what was originally supposed to be the Barbary Coast and include Tunisia, where I’ve long wanted to go, but world events interfered so Sardinia and Menorca were substituted, as well as extra time in Valencia, where in addition to one of the Holy Grails (housed in the cathedral there) we saw a parade in traditional garb — little girls in ruffled dresses and mantillas, elderly gents trying to manage their swords — and after that, in Granada, the magical Alhambra. That’s a place I’ve wanted to see with mine own eyes since my father rendered in paint how he imagined it looked in the Middle Ages.

Groups of tourists in unbecoming shorts and even more unbecoming hats, accessorized with running shoes and cameras with telephoto lenses the size of small cannons, couldn’t mar the spell of that place, the orange trees, the fountains, the intricate marquetry indoors, the view of the mountains behind the gardens and courtyards. There wasn’t enough time; I think there can never be enough time to soak in the details, the craft, the imagination and artistry that make up the whole that is the Alhambra, a fusion of cultures, Muslim and Christian, that gives me hope for the world.

In Malaga, where Picasso was born, we had a guided tour through yet another Picasso Museum — I’ve lost count of how many I’ve been in over the years — this one surely the revenge of the painter/sculptor/ceramicist’s children for paternal neglect. They established it with the art he had given them, and apparently he gave them the dregs. Of course if you make as much work as he did, not everything is bound to be a masterpiece, but at the same time, this museum enshrines some unforgivably bad work, with the exception of a couple of small portraits. Think if these were the only Picassos someone saw. That thought reminded me of Nureyev’s last performance in Eugene, when he was so diminished he wasn’t recognized by the audience, many of whom were seeing him for the first and only time.

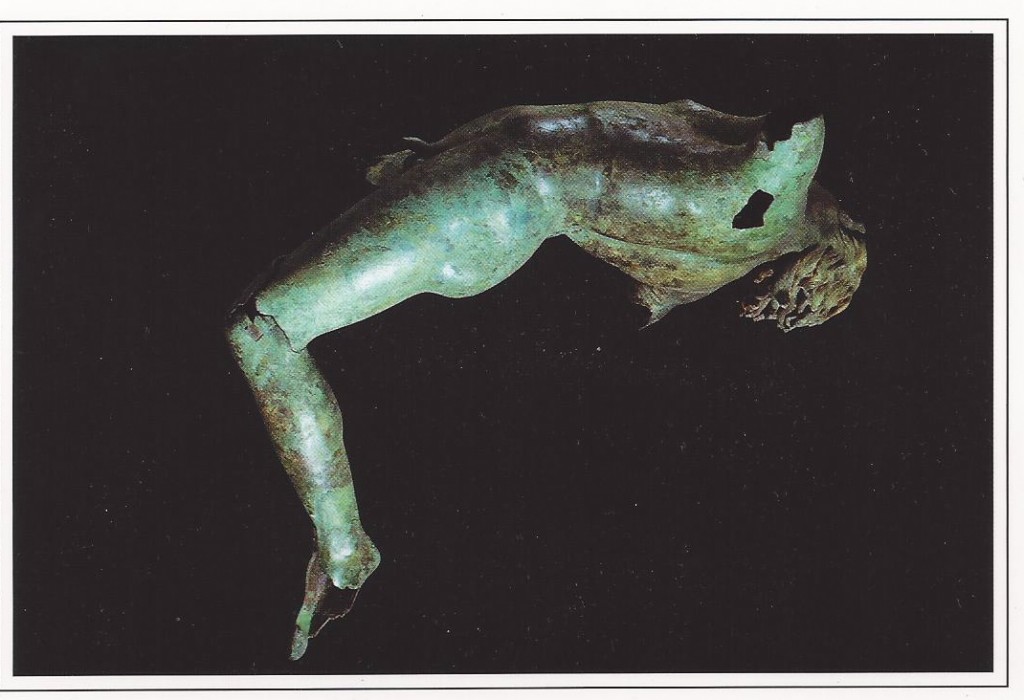

The closest we came to a dancer (except for a fellow passenger who, following a glass or two of something alcoholic, was moved to dance quite well to the beat of the ship’s cocktail pianist) was in the small but elegant museum of the fishing village of Mazara del Vallo, high in the hills above Trapani. There the Dancing Satyr, a 2000-plus (or minus) year old Greek or Roman statue (scholars continue to argue about the details) that landed in the nets of fishermen in 1998, was on display. It’s a magnificent piece; battered by time and tide, with bits and pieces missing, including the satyr’s tail, but clearly still dancing, perhaps to the tune of a flute, or maybe to the Greek or Roman equivalent of a brass band. The energy is certainly there, encased in greening bronze.

The closest we came to a dancer (except for a fellow passenger who, following a glass or two of something alcoholic, was moved to dance quite well to the beat of the ship’s cocktail pianist) was in the small but elegant museum of the fishing village of Mazara del Vallo, high in the hills above Trapani. There the Dancing Satyr, a 2000-plus (or minus) year old Greek or Roman statue (scholars continue to argue about the details) that landed in the nets of fishermen in 1998, was on display. It’s a magnificent piece; battered by time and tide, with bits and pieces missing, including the satyr’s tail, but clearly still dancing, perhaps to the tune of a flute, or maybe to the Greek or Roman equivalent of a brass band. The energy is certainly there, encased in greening bronze.

World and professional events caught up with us on the cruise, where mercifully we had no access to television news. The latest royal wedding took place, and those who were interested could watch a satellite feed in the lounge. (I did not.) Osama bin Laden bit the dust, and some passengers were not entirely thrilled that he was caught on Obama’s watch. The day after we saw the Dancing Satyr, I opened my e-mail (at great price: $4.50 a minute) and was poleaxed by the information that I was the recipient of this year’s Senior Critic’s Award from the Dance Critics Association, and thank you so much Mr. Scatter for the bouquets. That little piece of news made me start thinking about what I was going to say in the lecture/speech/talk I would have to give. Previous winners had talked about their first experiences of watching dance and writing about it, their personal backgrounds, what they had learned and what they wanted to pass on to future generations. I knew I would do the same, but what to emphasize? Looking at all the visual art, ancient, modern, contemporary, (I loved the Calatrava bridges and buildings in Valencia) helped me decide to speak about dance as a visual art, and barely mention the other part of my point of view, putting dance in historical and ethnographic context, the latter deeply ingrained in me by Margaret Mead, who was my godmother.

Back in New York, this West Coast critic’s hometown, I had an e-mail from my friend and colleague George Jackson to say I must not, must not, absolutely must not, miss the “black and white” Balanchine evenings taking place that very May week at the theater formerly known as the New York State Theater at Lincoln Center. I saw two, the first a matinee on Mother’s Day that included an underrehearsed Concerto Barocco and four Stravinsky ballets: Duo Concertant, which OBT does well, on this occasion danced by Chase Finlay, the new gorgeous kid on the block, partnering Megan Fairchild; Monumentum Pro Gesualdo, a gorgeously intricate ballet I’d somehow never seen before and would like to see again at least 10 times; Movements for Piano and Orchestra; and Symphony in Three Movements, all of them danced with supreme technical skill and the kind of heart and commitment that has been sadly missing from this company for nearly three decades. The applause for these plotless ballets was strikingly similar to what I used to hear — and participate in — at the old City Center, when some of these ballets were epiphanies of neoclassicism.

Two nights later I was back in the audience, sitting on the aisle, the seat next to me empty, for a program that opened with Square Dance, sans caller, and I’m bound to say I like it better that way: it’s much easier to see the intricacy of the pointe work, and it’s a real killer. OBT’s dancers acquitted themselves well, thanks to Victoria Simon’s coaching and ballet mistress Lisa Kipp, but not this well. Balanchine made this ballet in 1957 with the caller as a marketing gimmick, though you won’t read that part in any ballet history. There had been a profile in The New Yorker on Elisha C. Keeler, the original caller, and while Balanchine was genuinely interested in linking folk dance to ballet and revving it up to mach 1 speed, he was ever aware of what might sell tickets. In 1957, when NYCB was but eight years old, there was a pressing need to do just that.

Agon, which premiered a month after Square Dance, came next on this program, following a pause during which an elderly woman (even more elderly than Art Scatter’s highest-paid correspondent) scuttled into the seat next to mine. I hadn’t seen such an energized, skillful, jazzy performance of this ballet since 1958, when from a $1.75 seat in the second balcony I watched it for the first time, understanding it little and loving it much. Sean Suozzi, dancing Todd Bolender’s role in the Sarabande, infused his performance with the same insouciant wit, and Maria Kowroski and Sebastien Marcovici’s central pas de deux was a marvel of elegant seduction.

“I’ve never seen Agon before,” the latecomer commented as the lights went up for intermission.

“How come?” I asked her, astonished.

“I played in the orchestra for forty years and I had to watch the conductor, not the ballet,” she said reasonably.

She had started in 1958, at City Center, playing the harp, so I had heard her play many many times, we discovered together, in a wonderful New York moment. And I found myself glad she had seen Agon at its very best. Â The program ended with Episodes, originally a collaboration with Martha Graham, to music by Anton von Webern and Johann Sebastian Bach.

Note well: the week of “black and white” Balanchine ballets was sold out; audiences were cheering. What were they cheering about? Marvelous dancers performing genius choreography with all the heart, soul, technique and honesty they could muster. They weren’t pretending to be princes, dukes, enchanted princesses or happy peasants — they were dancing about dancing, about dancing to music, finding the joy in the art, and conveying it to a very responsive audience.

By the middle of May I was back in Portland, getting jittery about my speech, seeing with considerable pleasure the last two shows in the White Bird Season, Israeli choreographer Barak Marshall’s Monger at the Schnitz; and at the funky Alberta Rose Theatre, some witty, surrealistic work by Yossi Berg and Oded Graf (also Israelis) in a piece called 4 Men, Alice, Bach and the Deer. I’m still pondering the reason for the deer.

The clock ticked, the month changed, and it was time, past time, to buckle down and write that damned speech, titled The Education of a Dance Critic, or “I get by with a little help from my friends.” It was delivered on June 11 in Seattle, at the Phelps Center, Pacific Northwest Ballet’s building, where it occurred to me as I hid behind the lectern that I had spent a good deal of my thirty-year career covering the company for Dance Magazine, The Oregonian, and occasionally Ballet Review. The Dance Critics Association’s annual conference was being held in that building because of PNB’s new production of Giselle, staged by company artistic director Peter Boal, as the program says, “based on primary sources from Paris and St. Petersburg, with the assistance of dance historians Marian Smith [who teaches at the University of Oregon] and Doug Fullington.” This was the company premiere of the 1841 ballet, and Boal, who is deeply committed to contemporary choreography, decided to make it unique by reverting as faithfully as possible to the original. That meant more mime than the conventional wisdom says 21st century audiences can tolerate, a considerably larger cast of characters than is usual in today’s productions, and longer variations and set pieces.

And for the DCA conferees, there was a keynote speech by the Empress of Labanotation, Ann Hutchinson Guest (Labanotation was not one of the systems used to reconstruct Giselle; it’s a 20th century invention] plus panel discussions of the ballet and its history and of how this particular production was staged, with Boal, Smith, and Fullington explaining with impressive lucidity how and why they did what they did. On that first day there was also a discussion of reconstruction using “all available means,” and my own panel on reconstructing 20th century American ballet.

On the second day we had a panel on critical practice led by Marcia Siegel that was less than encouraging, but nevertheless interesting: clearly we must as critics embrace technology and social media, much as the latter corrupt the English language (friend, my friends, is not a verb); more perspectives on Giselle; and the final panel, called Curating History: How We Create the Past, which included Donald Byrd, whose Life Stories: Daydreams of Giselle was brilliantly paired years ago by James Canfield with OBT’s traditional Giselle.

And what of PNB’s extremely traditional Giselle, which I saw twice, with mostly different casts? I’ve seen a lot of productions of this ballet — in fact, the first 11 p.m. deadline review I did for The Oregonian was of Ballet Oregon and Eugene Ballet’s joint production of the ballet in 1988 — and it’s not easy to make me suspend my disbelief. Kaori Nakamura, however, made me do just that, moving me to tears in the mad scene, at the end miming “I’m dying,” definitely a 19th century touch. The audience was so absorbed, I might add, you could have heard a pin drop in that vast remodeled opera house. The next night Carla Korbes was technically better, lighter and more buoyant in the first act, but she did not move me. Of the two Albrechts I saw, Lucien Postlewaite was extremely good, partnering Nakamura. Karel Cruz, however, clearly needs considerably more experience before he can fully inhabit this role.

The Giselle we’ll see OBT do in February will not be like PNB’s, and that’s not necessarily a bad thing: there is room for many versions of this ballet, just as there is for Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty, The Nutcracker, and of course Petrouchka and Carmen, which will have been reimagined by Nicolo Fonte and Chistopher Stowell, respectively, when OBT opens its 2011-2012 season in October.

I look forward to seeing them, writing about them, putting them in context, responding from my gut and with my heart, to what I see. For that, really, is my process.

*

Illustrations, from top:

- Drawing of the RMS Mauretania, from a cigarette card, ca. 1922-29. Art Scatter’s highest-paid correspondent did NOT set sail on the Mauretania. New York Public Library/Wikimedia Commons.

- Allen Ullman, “Granada,” 1966, oil and casein. This is the author’s artist-father’s evocation of the way it might have looked in the Middle Ages. Courtesy Martha Ullman West.

- The Dancing Satyr in Mazara del Vallo. It was pulled from the sea in 1998 by fishermen, and might be Greek or Roman.