Sartre’s “No Exit” on the tilt, at Imago Theatre. Photo: Jerry Mouawad

Who wrote that play?

I don’t mean, did the modestly talented actor Will Shakespeare really write all those great stageworks, or was he just a convenient front man for Edward de Vere or some other dandy of the ruling class?

I mean, is the production you just saw actually of the play the playwright intended, or did it get reinvented so much in production that it actually became something else?

Charles Deemer has been gnawing on that bone as it relates to Jerry Mouawad’s critically praised production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit at Imago Theatre — a production that places the actors on an intricately balanced platform that shifts with every movement, echoing the tensions and balances among the characters.

Portland playwright Deemer first raised his objections in an Oct. 18 post on his blog, The Writing Life II. “Imago usually does original work, and brilliantly so,” he wrote. “It does original work here — it’s just misnamed. This production needs a little truth in advertising. It’s not Sartre. It’s variations on themes developed by Sartre. It’s interesting. It’s engaging. It just isn’t what the playwright intended and, as a playwright, I think this needs to be said.”

Deemer then followed up with comments on Martha Ullman West’s recent Art Scatter post about No Exit and a clutch of dance performances. “Composers do variations on a theme all the time and own up to it,” he wrote. “… What if someone went to the theater wanting to see the wonderfully grim original? What’s wrong with grim and cynical anyway?”

Then he added:

Let’s say a director resurrects Christmas at the Juniper Tavern and puts all the actors on roller skates because s/he believes it depicts the fluidity of their life journeys. Would I be amused? Guess.

“Edward Albee once closed down a production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf because George and Martha were presented as a gay couple.

“I once had the opportunity to ask Arthur Miller what he thought of an all-black version of Death of a Salesman that was done here with Tony Armstrong in the lead. ‘This is not the play I wrote,’ he told me.

“An advantage of the business of playwriting, as opposed to the business of screenwriting, is that playwrights retain ownership of their work. You legally can’t make changes without permission. Consequently I’ve long suspected that many, perhaps most, directors prefer their playwrights dead.”

Theater fans aren’t as volatile as opera fans, and it’s the rage these days in opera circles to boo directors and designers for undermining the music with conceptual approaches. Theater directors have been doing that for years (often, as Charles points out, with the work of dead playwrights who can’t fight back) and are lauded for it.

Interpretation is huge in the theater. But where does interpretation stop and something related but fundamentally different begin? Sometimes it seems like directors and designers use pre-existing works like especially fertile junkyards, discarding what they don’t want and mining them for treasure they can turn into something of their own. Novelists do that sort of thing all the time. But John Gardner didn’t call his book Beowulf. He called it Grendel.

What’s the essence of a play? Is it words? Is it tone? Is it the look of the thing? Or does it shift with every play, according to the play’s own core and elasticity? Putting the actors on roller skates for Christmas at the Juniper Tavern would absolutely change the play into something else. It MIGHT not irrevocably alter The Comedy of Errors.

As for Imago’s No Exit: As the script hasn’t been altered (so far as I know) it still seems to be Sartre’s play — but in English, not French, as Martha points out, and that raises the whole question of translation, which I think we’d better put off for another day. Charles is arguing, I think, that the INTENTION of Sartre’s play has been altered into something very different, and so in this form it can’t really be Sartre’s play anymore. I don’t know the original well enough to side with anyone on that, although I think directors and actors get intentions and tones wrong quite a bit. (Yes, Waiting for Godot is supposed to be funny.)

So. Intention seems important. I remember when Albee put the kibosh on the gay Virginia Woolf production, and I thought he was within his rights to do so. He said if he’d wanted George and Martha to be gay he’d have written them gay, and it would be a different play. So, even though Albee is gay and George and Martha bitch like an old gay couple of that time, the production was a leap from character interpretation to a radical revision of the play itself. It’s OK to say George and Martha are LIKE an old gay couple but not, Albee argued, that they actually ARE one.

So. Intention seems important. I remember when Albee put the kibosh on the gay Virginia Woolf production, and I thought he was within his rights to do so. He said if he’d wanted George and Martha to be gay he’d have written them gay, and it would be a different play. So, even though Albee is gay and George and Martha bitch like an old gay couple of that time, the production was a leap from character interpretation to a radical revision of the play itself. It’s OK to say George and Martha are LIKE an old gay couple but not, Albee argued, that they actually ARE one.

The author’s attitude does matter, even though once you’ve written something and released it to the world, the world also has a certain ownership. Another playwright might have said, in effect: “Interesting: Not what I had in mind, but worth looking at,” and that would have changed the equation. The next production would have returned to the original, and life would have gone on.

Miller, I think, was on a little shakier ground. Because Willy Loman wasn’t written as a black man doesn’t mean he couldn’t have been black — or that those experiences couldn’t have been felt by a black family. There might be a line here and there where you have to suspend disbelief a bit, but not much — and theater’s all about suspending disbelief, anyway.

The biggest conceptual roadblock might be historical: Would a black man ever have been given a sales route to begin with at that time and place in American culture? To worry overmuch about that, though, might mean you’re spending too much time thinking of the actor as a black man and too little thinking of him as Willy Loman.

The biggest conceptual roadblock might be historical: Would a black man ever have been given a sales route to begin with at that time and place in American culture? To worry overmuch about that, though, might mean you’re spending too much time thinking of the actor as a black man and too little thinking of him as Willy Loman.

While Virginia Woolf is specifically about a marriage, Salesman is not specifically about a white family. That’s part of the texture, but not the play’s essence. And while casting a black man as Willy might add nuance and shift the audience’s political and cultural approach to the material, it doesn’t alter the core of the play. Once you’re inside the meat of that thing, any good actor isn’t his outside self anymore: He’s Willy Loman, tragic figure and American icon. He could be green and it wouldn’t make a difference. (On the other hand: Could a white actor successfully star in August Wilson’s Fences? I’d argue no, because Troy’s race so completely identifies his essence in his own eyes and in the eyes of the world.)

Theaters across the country have been routinely casting shows “color-blind” for years. That reflects America’s multiracial, multiethnic contemporary culture, and theater needs to be part of its times if it’s going to survive. Does anyone blink when a black actor plays the father or son of a white actor at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival? An actor is an actor, and it’s the quality of the performance that counts. This sort of casting is just accepted stuff in contemporary society.

Sometimes, depending on the script, it can shift meaning, and it can shift it most interestingly when race is already part of the equation. I remember a black actor in Ashland many years ago telling me it was his ambition to play Iago: Othello made the most sense to him, he said, if both Iago and Othello were black men, and thus outsiders. Othello would see Iago as his most trusted friend, the one person who understood him, even more than his white wife could. Iago would resent that Othello was, in effect, the chosen one — the outsider who was given all the honors. And he would hate him for that. A fascinating idea, and I don’t know that the actor ever got to carry it out.

Time plays a role, too. Maybe directors and designers perpetrate their deeds on dead playwrights because old plays take on new potential meanings when cultures and assumptions shift. A work of art isn’t only an aesthetic creation. It’s a social construction, too — and societies change.

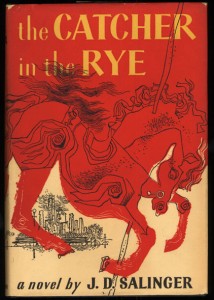

Artists have a right to their own creations. But audiences and interpreters have rights, too, and I’m not sure there are any one-size-fits-all answers. That’s why courtrooms and lawyers keep getting in the middle of things. I do think J.D. Salinger went far beyond his legitimate rights of ownership when he sued to stop publication of a new novel, with a new title, that imagined Holden Caulfield as an old man. The new novel was undeniably derivative. It was also undeniably a new work of the imagination, with a new title, that made no claim to being the original.

Artists have a right to their own creations. But audiences and interpreters have rights, too, and I’m not sure there are any one-size-fits-all answers. That’s why courtrooms and lawyers keep getting in the middle of things. I do think J.D. Salinger went far beyond his legitimate rights of ownership when he sued to stop publication of a new novel, with a new title, that imagined Holden Caulfield as an old man. The new novel was undeniably derivative. It was also undeniably a new work of the imagination, with a new title, that made no claim to being the original.

Does Salinger own Holden Caulfield? Yes and no. He owns the words inside the covers of The Catcher in the Rye, in the order and combinations that he created, and he owns his share of the proceeds from any publication of the book. But although he was the creator, I’m not sure anyone owns the IDEA of Holden Caulfield anymore. He’s out there in the universe, and he’s not coming back.