A quarter-century after a literary landmark in Oregon, and the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Let’s see. Urban/rural split, with a vengeance. A recession in the city, which means a depression in the small towns and countryside. Newcomers wide-eyed with enthusiasm over their new home; old-timers narrow-eyed with suspicion and mistrust. Jobs disappearing as fast as the trees and fish. An almost desperate love for the land. Merry Christmas, everyone!

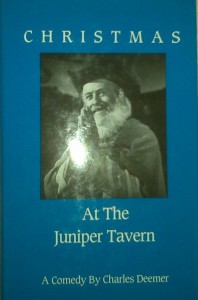

A few evenings ago I sat down and re-read Charles Deemer‘s 1984 stage comedy Christmas at the Juniper Tavern. It was maybe the third or fourth time I’ve read it in the 25 years since it debuted, to great acclaim, at the old New Rose Theatre in Portland. In that time I’ve scratched my head repeatedly over why some Portland theater company doesn’t revive it for a December run. It’s topical, it’s seasonal, it has terrific characters and it gets to the heart of that elusive thing called the Northwest spirit. I’m convinced that with a good production it’d be a hit.

A few evenings ago I sat down and re-read Charles Deemer‘s 1984 stage comedy Christmas at the Juniper Tavern. It was maybe the third or fourth time I’ve read it in the 25 years since it debuted, to great acclaim, at the old New Rose Theatre in Portland. In that time I’ve scratched my head repeatedly over why some Portland theater company doesn’t revive it for a December run. It’s topical, it’s seasonal, it has terrific characters and it gets to the heart of that elusive thing called the Northwest spirit. I’m convinced that with a good production it’d be a hit.

***

Well, maybe next year. In the absence of a fresh production, the next best thing is a trip on Wednesday evening to the Blackbird Wine Shop, at Northeast Fremont Street and 44th Avenue in Portland, for a 25th anniversary showing of Juniper Tavern‘s original broadcast on Oregon Public Broadcasting. A digitized version of the broadcast will be shown 7-9:30 p.m. Dec. 9. Admission’s free, and wine tasting is five bucks.

***

The DVD version, a copy of which Deemer sent me, is a mixed bag. It’s pretty much a point-and-shoot affair, a visual recording of that terrific original production, without the kinds of camera movement and visual rethinking that a higher budget might have brought to the project. That makes it, cinematically, more static than it ought to be.

But it also faithfully reproduces what was a top-notch stage production, solid across the board but sparked by the chemistry between Vana O’Brien as down-to-earth bar owner Stella and the late Rollie Wulff as Frank, an unemployed mill worker trying to make sense of a rural world that’s falling apart on him.

Their story is interrupted and amplified by a drinking binge, a stolen Rolls Royce, an abortive kidnapping, an angry mother in pursuit of her blissed-out daughter, a Christmas pageant, and — oh, yes — original director Steve Smith’s shockingly funny performance as Swami Kree, an Indian guru whose followers, who are building an ashram in the Central Oregon desert, have given him 26 Rolls Royces and one cool cowboy hat.

Deemer wrote Christmas at the Juniper Tavern at a time when a New Agey international religious group called the Rajneeshees and their guru, Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, had taken over the tiny town of Antelope in Central Oregon and renamed it Rajneeshpuram.

It was one of the unlikeliest and most sensational stories in Oregon history. The split between the mostly wealthy Rajneeshees and the locals was sharp and radical. In a plot to take over Wasco County politically, members of the ashram under the direction of the bhagwan’s right-hand woman Ma Anand Sheela (echoed smartly in the play by Jane Titus as the waspish Ma Prama Rama Kree) spread salmonella poisoning through several restaurants in The Dalles, hoping to sicken enough voters that their own members would dominate the coming election. Rajneesh, who at one point had 90 Rolls Royces rolling in and out of the ashram, was eventually deported back to India.

The parallels between the Rajneeshee movement and Christmas at the Juniper Tavern were obvious, and audiences and critics alike assumed the play was a comic riff on current events. Deemer declared his play was not about the Rajneeshees (more on that below) but people didn’t pay much attention. Now, the play’s broader themes are easier to see.

As neatly as it strikes the historical chords of an outrageous cultural clash, in a larger sense Juniper Tavern belongs with a series of plays Deemer wrote in the 1980s about the social and economic strains of mostly small-town life in the Northwest. He included it in his 2006 collection Country Northwestern and Other Plays of the Pacific Northwest, which also included the title play plus Varmints, Waitresses and The Half-Life Conspiracy. Those plays mark a considerable achievement in documenting, with insight and humor, both the stubborn will of the region’s hardscrabble rural romantics and the fading of a way of life.

Listen to Rex (Gary Brickner-Schulz) in his monologue at the top of Act Two of Christmas at the Juniper Tavern:

“The bottom line is, you gotta eat. I don’t know what Margie expects me to do. You won’t find a harder working sum-bitch than yours truly but I can’t open up the mill if the company don’t want it open. If the mill ain’t open, I can’t haul logs. It’s that simple.

“There was a time when I’d’ve hit the road by now. But, damn it, I love this part of the country. I love Central Oregon. I love Juniper, the home I’m buying, my neighbors, the kind of life we share. I wake up in the morning, look out my kitchen window, and see nothing but snow-capped mountains. A rich man can’t see anything prettier.

“But you gotta eat, is what I’m saying. And if there ain’t work in the woods, you gotta find something else. You gotta use your imagination.”

I’ve spent time this year in some far corners of the Pacific Northwest. Twenty-five years ago I couldn’t have used free wifi or probably found a good cup of coffee in LaGrande, and both are easy now. Still, a quarter-century on, Rex’s description of the problem and the vague search for a solution seems uncannily familiar.

***

Back to Christmas at the Juniper Tavern and the Rajneeshees. A few weeks ago Deemer sent me this explanation for how the play actually came about:

“Now that you’re revisiting Juniper, maybe you’d be interested in the true roots of Swami Kree. They are different from what folks assumed at the time.

“In grad school, when I began teaching, I became interested in the possible pedagogic uses of paradox and contradiction. This culminated in a very controversial academic article, English Composition as a Happening, that was published in College English in 1967. … Later I discovered a thin book called Zen and the Comic Spirit. Historically, many zen masters used paradox and contradiction in their teachings. One was a 13th century monk named Teng Yin-feng. Teng presumably, as a lesson to his students, died standing on his head. In 1975, before moving to Portland, I wrote a one-act play called The Death of Teng Yin-feng. This was my first attempt at Swami Kree.

“In 1983 I was commissioned by New Rose to write the Moliere play [The Comedian in Spite of Himself; later revised as Sad Laughter]. I had a situation where I could live rent-free in Bend and went there. The papers there were full of Rajneeshee news, much more than in Portland. Also, the Bhagwan was on his vow of silence. This latter is hugely important. If he had been talking, he would not have fascinated me because once he talked, he just sounded like a politician to me. But silent, I could fantasize that he was a Zen clown.

“Bend was full of unemployed mill workers. What on earth would these two camps have to say to one another once the vow of silence ended? This was the question that created the play, fueled by my long interest in paradox and contradiction as methods of knowledge and enlightenment. Yes, the Rajneesh were an influence of sorts — but Eng Comp as a Happening and Teng Yin-feng are far greater contributors to the DNA of Swami Kree.”