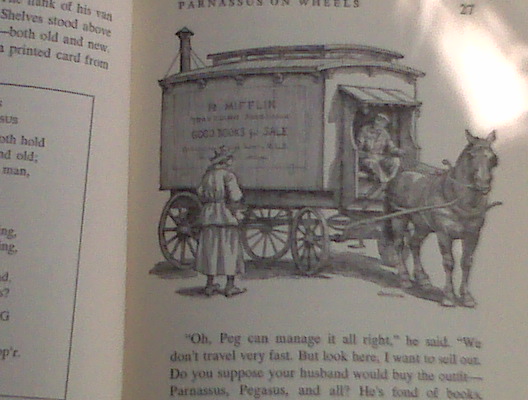

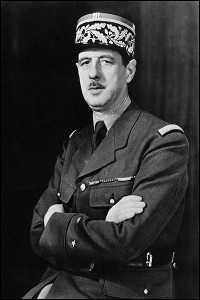

Parnassus on Wheels, by Christopher Morley, 1917. Illustration by David Gorsline, 1955 edition, J.P. Lippincott Company.

————————————-

Mount Parnassus, as you’ll recall, is the home of the Muses, rising above Delphi in Greece. For that reason the word “Parnassus” has come to stand for music and poetry in particular, and for literature and learning in general — if not for civilization itself, then for those things that make a civilization worth building.

With only one show Wednesday at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland — Much Ado About Nothing, in the evening on the open-air Elizabethan Stage — my sister Laurel and I spent the afternoon rustling around in book shops along Main Street.

There is, of course, Bloomsbury Books, at the south end of downtown, a good general new-books store that I’ve been visiting off and on for more years than I can remember, and where I’ve made many a find, including John Updike’s novel Gertrude and Claudius, an imagining of the events that led up to the events in Hamlet. This time I was looking for a specific book, David S. Reynolds’ history Waking Giant: America in the Age of Jackson, and it wasn’t there.

So we crossed the street and, leaving the realm of the new, embarked upon the fascinating, tempting, nostalgic, disorienting and reorienting world of what once was.

It’s hard to imagine two used book shops that put on such different faces as the pair along the east side of Main in this literate foothills town.

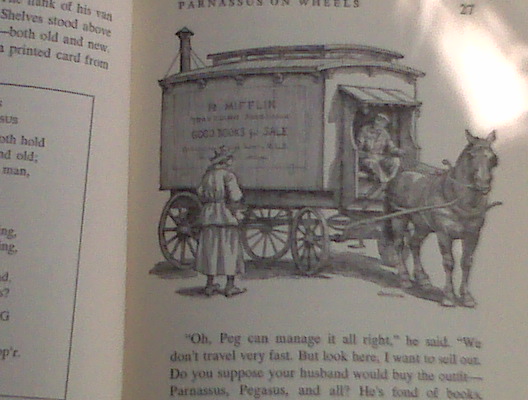

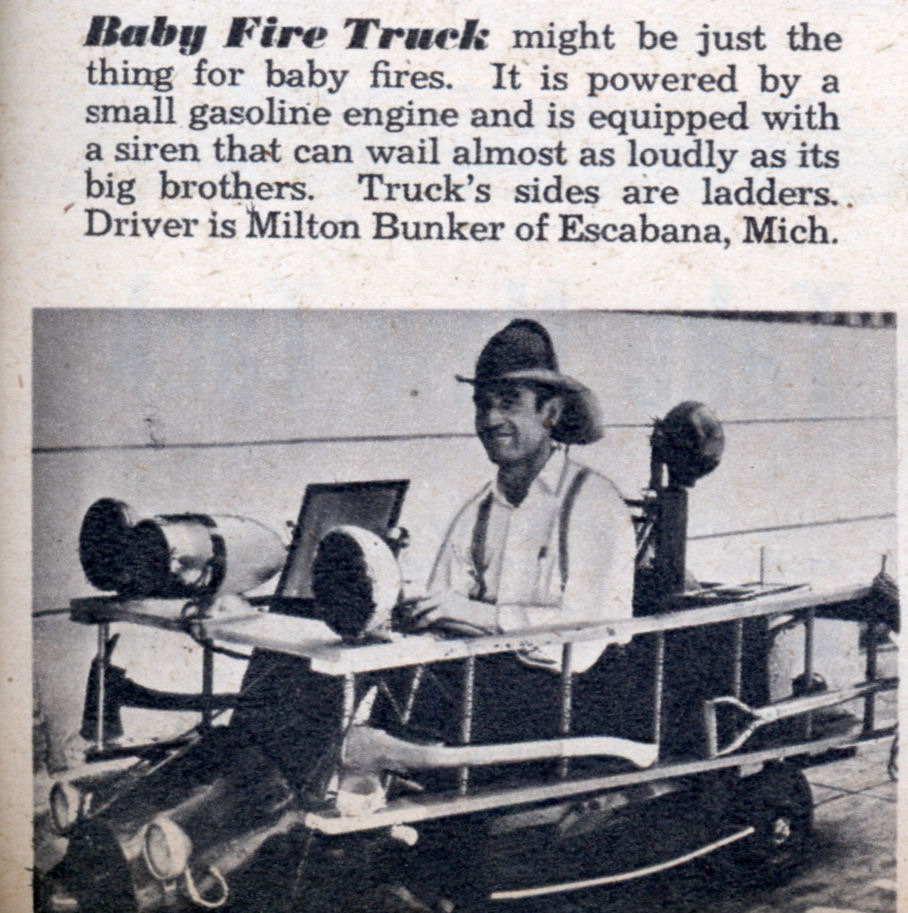

Shakespeare Books & Antiques, closer to the festival grounds, is the work of a collator, a curator, an ordered and interesting mind. Everything is neatly lined, carefully arranged, comfortable. The antiques are lovely and tasteful, from a wondrously detailed old cast iron fire engine to sets of beautiful blue china. The place is an invitation, evoking images of rose petals and tea. And the books are handsome and substantial: You could spend hours happily checking these shelves.

The Blue Dragon Book Shop, just across from Bloomsbury, is an old curiosity shop — a clutter of loosely arranged subjects and oddities, a rambling undergrowth fertile with possibility for hardy explorers hacking their way through with sythes. Old sheet music flutters on one table. Another holds mid-1950s copies of Playboy and 19th century editions of Harper’s Weekly with Thomas Nast’s Civil War illustrations. You need to watch your feet, if not for snakes, then for makeshift standing shelves jutting into the aisles.

When an old book interests me I open the pages and smell it. The smell can be dank and chemical and spoiled, like a bottle of corked wine, and that’s the end of it: The deal’s off. Or it can smell of old wood and dried leaves and mushrooms on a log, a smell that only time and settling-in can achieve. That’s the book for me — if not to buy (I do have a budget, and a limited amount of book space) then to handle, to hold, to feel with my fingers and take in with my eyes before reluctantly returning it to its shelf.

I find an 1898 children’s book, Who Killed Cock Robin? and Other Stories, which has ornate illustrations and gives a lively alternate version to the old poem and is, I realize, a bargain, but not one I choose to afford on this day. I pick up a nicely printed copy of Francis Parkman Jr.’s The Oregon Trail, with excellent drawings, that smells good and is in good shape at a good price. But it plows straight into the story (first published as 21 installments in the old Knickerbocker Magazine in 1847-49) with no introduction, and if ever a book needed to be set properly in its time and place, The Oregon Trail is it. I leave it for another person on another day.

At Shakespeare Books Laurel discovers several editions of the Edward Fitzgerald translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, each with its own elegant illustrations, none quite like the edition we grew up with, which Laurel now owns, complete with unfortunate childish pencil doodlings on the opening pages.

At the Blue Dragon she calls me over from a row away, where I’m looking through a two-volume 1940s edition on pre-Columbian art, Medieval Art of America. I like to look through books published during World War II, which often are on thick pulpy paper and usually smell alive and are testaments to the determination to make beauty even in a time of scarcity. Sometimes too much scarcity. Medieval Art of America seems thorough, and serious, and impeccably researched. But it contains not a single illustration of the art it so painstakingly catalogues.

“Do you remember this?” Laurel asks, handing me a slim, well-bound copy of Christopher Morley’s 1917 novel Parnassus on Wheels. This is a 1955 edition from J.P. Lippincott Company, with fine line illustrations by Douglas Gorsline, and whether it’s the same as the one in my father’s collection I can’t recall (Laurel has that one now, too) but it smells like a bright autumn day and it’s ten dollars and I buy it.

Parnassus on Wheels is the unlikely and whimsical story of a New England farm woman in the early years of the 20th century who buys a traveling horse-drawn van complete with horse (named Pegasus) and dog (Boccaccio, or Bock) and gads about the countryside, selling books to farm and town folks. As a child the story reminded me of the library bookmobile that made regular visits to the farms of friends. As a townie I could walk easily to the library on my own, but sometimes I wished the bookmobile would stop at my house, too.

Continue reading Ashland 2: Much ado about book shops →

Today, after a matinee performance of All’s Well That Ends Well, the extended Scatter Family leaves Ashland and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival for dinner, bed and breakfast at the old Wolf Creek Tavern north of Grants Pass before a Labor Day drive back to Portland.

Today, after a matinee performance of All’s Well That Ends Well, the extended Scatter Family leaves Ashland and the Oregon Shakespeare Festival for dinner, bed and breakfast at the old Wolf Creek Tavern north of Grants Pass before a Labor Day drive back to Portland.

This season’s lark is The Servant of Two Masters, the 18th century Italian comedian

This season’s lark is The Servant of Two Masters, the 18th century Italian comedian

It’s almost as if we’ve turned this towering, talented, shrewd and savage leader into a pet — and so, in a way, does Shakespeare in Henry VIII, his final play. When it came to politics Shakespeare, whose company was sponsored by the king, played a necessarily careful hand (see Equivocation, below). His Henry, while hardly blame-free, is a generous-hearted fellow, good to his courtiers, solicitous of the feelings of the wife he’s dumping after 20 years, self-persuaded that his exchange of used-car Katherine for racy new convertible Anne is a matter of conscience, and painfully misled in matters of taxation and treachery by that rascal of a right-hand man, Cardinal Wolsey. In meticulously pruning the monarchial vines Shakespeare’s created a fine hearty fellow, if a little mixed-up and dense — and if there’s one thing the real Henry was not, it’s dense.

It’s almost as if we’ve turned this towering, talented, shrewd and savage leader into a pet — and so, in a way, does Shakespeare in Henry VIII, his final play. When it came to politics Shakespeare, whose company was sponsored by the king, played a necessarily careful hand (see Equivocation, below). His Henry, while hardly blame-free, is a generous-hearted fellow, good to his courtiers, solicitous of the feelings of the wife he’s dumping after 20 years, self-persuaded that his exchange of used-car Katherine for racy new convertible Anne is a matter of conscience, and painfully misled in matters of taxation and treachery by that rascal of a right-hand man, Cardinal Wolsey. In meticulously pruning the monarchial vines Shakespeare’s created a fine hearty fellow, if a little mixed-up and dense — and if there’s one thing the real Henry was not, it’s dense.

The festival’s Don Quixote is a world-premiere adaptation by the playwright

The festival’s Don Quixote is a world-premiere adaptation by the playwright

“No kissing of ring necessary,” his partner, Sherry Lamoreaux, insists. But we can scarce restrain ourselves.

“No kissing of ring necessary,” his partner, Sherry Lamoreaux, insists. But we can scarce restrain ourselves. It’s 30 minutes long, and

It’s 30 minutes long, and

Just imagine, if you will, bras and Alvin and the Chipmunks.

Just imagine, if you will, bras and Alvin and the Chipmunks.

The intrepid Mighty Toy Cannon has the story at Culture Shock;

The intrepid Mighty Toy Cannon has the story at Culture Shock;