Above: Truffaldino, the servant of two masters (Mark Bedard), takes a break from his dizzying existence. Inset below: The old tightwad Pantalone (David Kelly) is overjoyed at the prospect of receiving more gold. Photos: Jenny Graham/Oregon Shakespeare Festival/2009.

Every season at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival needs its lark, that well-turned show of comic wordplay that, while it may or may not also have more serious things on its mind, celebrates the wit and technique and sheer fun of the theater itself.

From the old days of Wild Oats and The Shoemaker’s Holiday and Taking Steps to the more recent likes of On the Razzle and The Philanderer and The Further Adventures of Hedda Gabler, the festival has long delighted, and delighted its audience, in theatrical self-reference. Such plays speak to the magical duality of theater, and of art in general: It is of utmost seriousness, and of little consequence. The ability to defend and revel in its inconsequence is a matter of importance in a human society that is constantly expanding and shrinking its limits of permitted expression. In a culture where power calls the shots, the liberating qualities of comedy, which so often crumbles deceits beneath the prodding thumb of ridicule, can be more dangerous than tragedy.

Then again, maybe it’s all just fun.

This season’s lark is The Servant of Two Masters, the 18th century Italian comedian Carlo Goldoni‘s own masterwork, in a world-premiere adaptation by Oded Gross and director Tracy Young from a literal translation by Beatrice Basso. It is, quite simply, more fun than a barrel of monkeys.

This season’s lark is The Servant of Two Masters, the 18th century Italian comedian Carlo Goldoni‘s own masterwork, in a world-premiere adaptation by Oded Gross and director Tracy Young from a literal translation by Beatrice Basso. It is, quite simply, more fun than a barrel of monkeys.

Goldoni, who began his career in Venice and moved on to Paris in disgust over the state of theater in Italy, approached the old Italian form of commedia dell’arte through the prism of the French master Moliere and looked ahead to the 20th century collaborations of Dario Fo and Franca Rame. What he achieved was a marvel of comic construction that is at once as tight as a well-tuned drum and as loose as a good jazz improvisation.

Commedia is essentially a form of street theater, with stock characters who are familiar to the audience and who play to form but vary the details to fit the time and place. Thus commedia was always traditional and always as fresh as a daily scandal sheet. Moliere took the form and translated it into literature. Fo and Rame kept the literary qualities but took things back (at least metaphorically) to the streets.

The Shakespeare Festival’s updating of The Servant of Two Masters keeps the action on the stage but with a more than vigorous nod to the trials, tribulations and absurdities of contemporary life beyond the theater walls. You can’t exactly call this Poor Theatre: Despite the Great Recession that this show lightly mocks, the festival is a well-endowed company, and it loves to use the technical gadgets that money can buy. But this production’s emphasis is definitely on the illusions of smallness: the things that a troupe of talented actors with a ragbag of tricks can achieve. And for the festival it’s stripped down: just a stack of small risers in the center of the theater in the round, plus poppings-out from platforms at the four corners of the small New Theatre. Christal Weatherly’s brightly witty patchwork costumes carry the day. (I’m especially fond of the Dottore’s improvised academic mortarboard, made from an LP jacket for Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass’s album Whipped Cream and Other Delights.)

How much of this Servant of Two Masters is Goldoni and how much is his latter-day adapters? Certainly the plot, a lightly silly clothes hanger of a thing designed to hold the asides and physical bits in place, is Goldoni’s. Truffaldino, the servant (Mark Bedard), shows up in Venice just as Pantalone’s daughter Clarice and a fop named Silvio are preparing to be married. Truffaldino is in service to Federigo, who is actually Federigo’s sister Beatrice in disguise, who is seeking her beloved Florindo, who may or may not have murdered the real Federigo, and who arrives in town and also hires Truffaldino as his servant, and …

There’s no use giving out any more of the plot. It matters, but only when you’re watching. Let’s just say it’s tangled, and ridiculous, and highly amusing. As for the rest, while Gross and Young have taken huge liberties with the writing (and while a certain amount of improvisation works into every performance), it’s clearly in the spirit of Goldoni and commedia. Like Bill Cain’s new play Equivocation, The Servant of Two Masters refers liberally to other shows in the current season and beyond: When one of the characters shudders at a mention of “The Scottish Play,” romantic hero Elijah Alexander blinks in confusion and replies, “Brigadoon?”

You can’t be this loose on stage without first being tight (no, that’s not a reference to drinking in the rehearsal hall), and this show is a marvel of collaborative craftsmanship. The language is quick and sharp and from the front of the mouth; the action is fleet and sure-footed; the shtick is rigorously rehearsed; the stylized flourishes are easy and exaggerated; the whole thing roars by like a paisley toy locomotive.

Topping off the joy of this Servant of Two Masters and letting it take flight is what theater folk call “breaking down the fourth wall” and civilians call simply “playing with the audience.” Bedard and others banter with people in the crowd, cadge candy and sandwiches, flirt, mock, sit down and chat. Pretty soon the audience is shouting back at the actors, hissing, crying out warnings and suggestions, and generally laughing like hyenas in a room full of helium.

You just don’t see that sort of thing in Macbeth. Even when the witches — pretty stock characters, themselves — are cackling their silly incantations over their smelly stewpot.

.

Clarice (Kjerstine Rose Anderson) and Beatrice (Kate Mulligan), disguised as Federigo, come to a new understanding. Photo: Jenny Graham/Oregon Shakespeare Festival/2009.

And on the second morning he got up, made coffee, and wrote his review, which was subsequently published (the review, not the coffee) in The Oregonian. And the review praised some and quibbled some, and was not, in the terminology of the great god Variety, boffo.

And on the second morning he got up, made coffee, and wrote his review, which was subsequently published (the review, not the coffee) in The Oregonian. And the review praised some and quibbled some, and was not, in the terminology of the great god Variety, boffo.

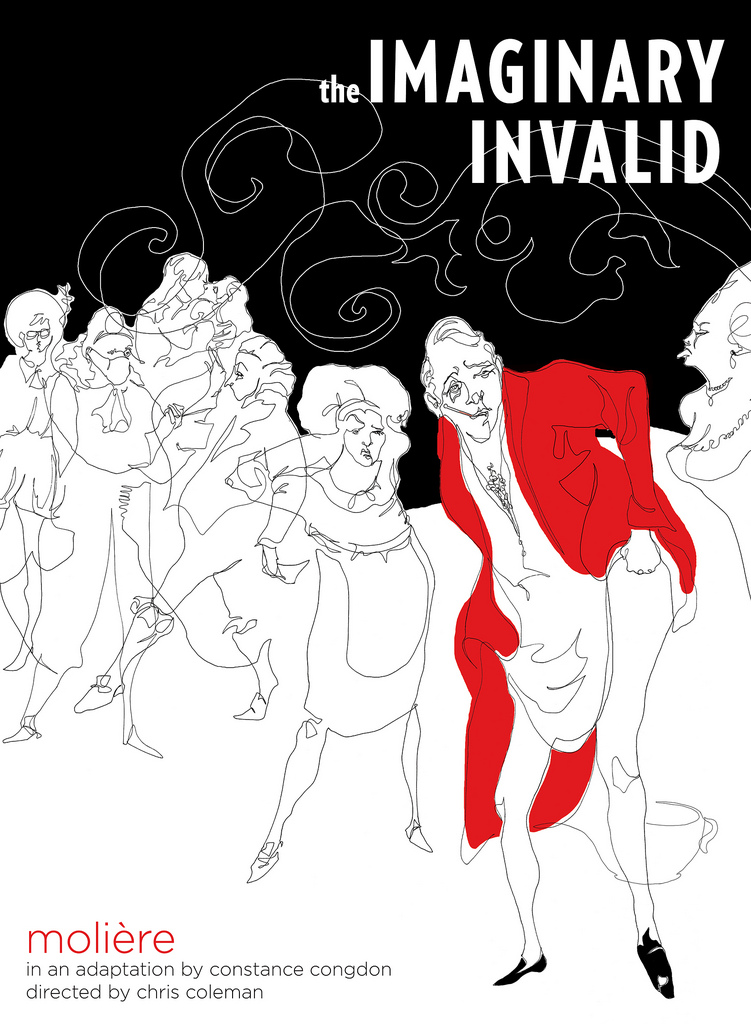

Pepys had notoriously little patience for Shakespeare and his fripperies. What might he have thought, then, of Constance Congdon’s adaptation of Moliere’s

Pepys had notoriously little patience for Shakespeare and his fripperies. What might he have thought, then, of Constance Congdon’s adaptation of Moliere’s

This season’s lark is The Servant of Two Masters, the 18th century Italian comedian

This season’s lark is The Servant of Two Masters, the 18th century Italian comedian