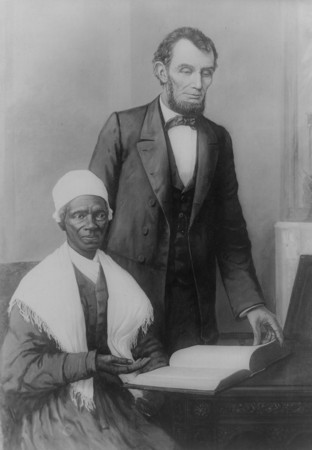

When I was much younger, I marveled at Election Day, this First Tuesday in November when Americans en masse, from sea to shining sea, returned to the polls to exercise the primary ritual of a democracy. The idea of it as a collective enterprise, the voting I mean, just made me happy somehow, even when I despaired over the outcome and had profound doubts about those we elected, even on the rare occasions when I actually voted for them.

When I was much younger, I marveled at Election Day, this First Tuesday in November when Americans en masse, from sea to shining sea, returned to the polls to exercise the primary ritual of a democracy. The idea of it as a collective enterprise, the voting I mean, just made me happy somehow, even when I despaired over the outcome and had profound doubts about those we elected, even on the rare occasions when I actually voted for them.

That was when I equated voting with democracy, before I realized that people could vote and have almost no effect on their government or its policies or that the manipulations of skilled and extremely well-funded propagandists (and I use this charged word deliberately, though I could simply have used “ad men”) could change an election. And over time, erode the democracy itself by diminishing our very capacity to make informed choices. Voting is not the same as democracy. I can’t show up every four years to vote for the lesser of two evils and think of myself as doing anything so important as participating in a democracy. A lot of the time, that’s what I’ve done. Democracy requires a lot more participation than that.

We know this has happened. Fully one-quarter of us aren’t registered to vote. Of those of who are, one-third won’t. So fifty percent of us acknowledge the futility of voting, understand that once our representatives get to Washington they make thousands of decisions that have nothing to do with our welfare, nothing to do with “representing” us, become entangled in networks of power that defy their abilities to change things, if they still have the heart. Those of us who do vote have become cynical about it. Let me re-phrase that: I have become cynical about it. Because I don’t want to speak for you. I vote and I walk away. I vote and I turn my nose. I am bad for democracy.

Continue reading Art Scatter says vote often