By Bob Hicks

It’s pretty grim, according to Steve Law’s report, Historical Society may ask voters for tax levy, in The Portland Tribune, and Sarah Mirk’s followup, State History Museum Will Run Out of Cash in 2011, Pitches Tax To Stay Afloat, in The Mercury’s Blogtown.

Things are skeletal right now. Oregon Historical Society boss George Vogt says that Oregon ranks No. 50 in state support of its history museum. Not sure, but that sounds like dead last, unless they’re counting the likes of Guam, Puerto Rico, American Samoa, and Washington, D.C. in the rankings.

The state of Oregon, strapped for funds like every other state, has basically thrown its hands up and surrendered. The Historical Society is so far down the list of its priorities, it’s probably looking up at the likes of funding for bicycle lanes on logging roads in the Tillamook Forest (where something called the Tillamook Burn once happened, but looks like that’s, well, history now).

Vogt says the society will run out of cash next year. His solution? A five-year, $10 million levy on the November ballot that would add about $10 a year to the property-tax bill on a $200,000 home. The catch? It’s not a statewide levy — it’s just for Multnomah County. One of the undertold stories of Oregon politics is that greater Portland and the Willamette Valley have been paying a big share of the bills for most of the rest of the state for decades (urban Oregonians pay much more into the state coffers than they get back in services, and the “extra” money helps underwrite rural and small-town Oregon) but you rarely see it spelled out as baldly as this. The payoff: Multnomah County residents would get free admission to the museum, which ordinarily costs $11 for adults.

Portlanders tend to believe in their cultural organizations, and in ordinary times this would probably stand a fair chance of passing. But these aren’t ordinary times, and I’m guessing this levy, if it hits the ballot, will face a steep uphill challenge.

Thoughts on this? Hit that comment button, please.

*

The picture at top, by Seattle photographer Tom Feher, is just one of his many images of Oaxaca, Mexico, on view Aug. 21-Sept. 24 at Portland’s Camerawork Gallery. There’ll be an artist’s reception 1-4 p.m. on Saturday the 21st. Feher’s exhibit, In the Navel of the Moon, is all about history, and the ways that history persists into the present, subtly and sometimes not so subtly shaping what we think of as contemporary life.

Feher has been photographing life in Oaxaca for a dozen years, and lives there half of every year. Here are some of his thoughts on what’s become something of a life work:

Life, in all its aspects, is multilayered in Mexico generally, and especially so in Oaxaca. At its most superficial there is what the tourist sees: the color, the festivities, the unsettling chaos of the markets, streets and traffic. But it goes deeper than that. The countless churches built upon the remains of ancient temples; the religious services and celebrations, an admixture of the orthodox and the older native practices. City names, often a combination of the indigenous name with a post-conquest Saint’s name tacked on. Contemporary art frequently contains pre-Hispanic imagery. Even the food has its origin in the indigenous dishes that existed before the Spaniards came. It becomes evident that even as they live in an ever more contemporary world, there are people of today’s Mexico who still dream the dreams of the ancients and evidence it in their daily lives, as well as events that only thinly disguise their connection to rituals of pre-history.

Ah, but then again, history: Who needs it, anyway?

*

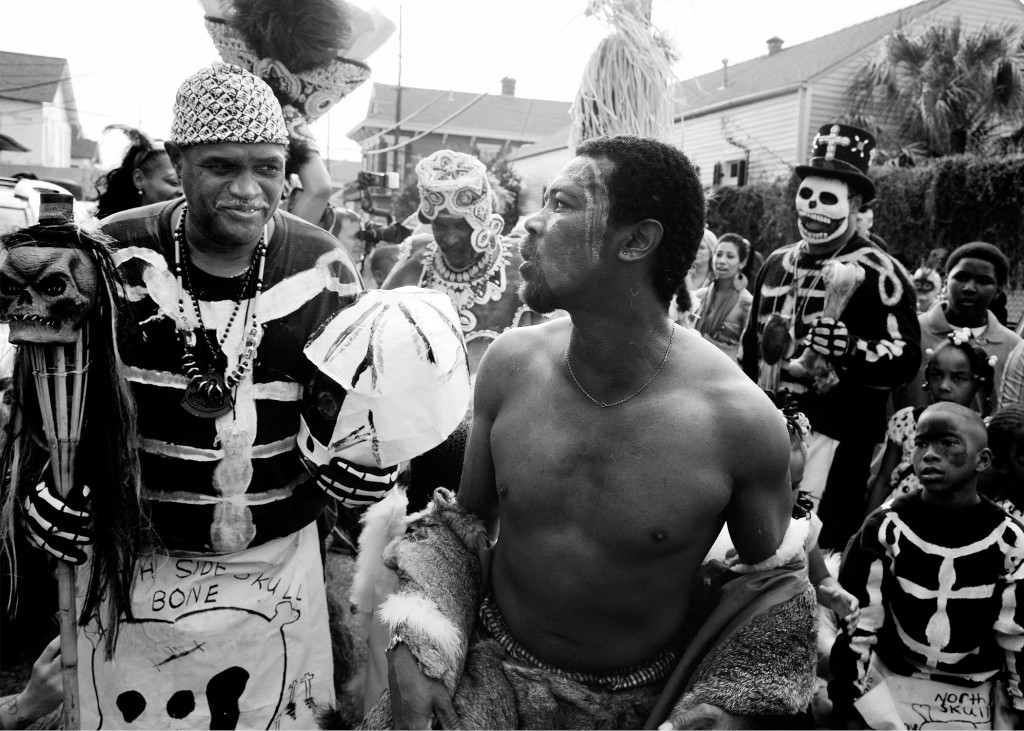

Intriguingly, Northeast Portland’s 23 Sandy Gallery has a show coming up in September that seems to dovetail in interesting ways with Feher’s exhibit at Camerawork. Portland photographer Stewart Harvey‘s I Am What I Need To Be, on view Sept. 3-18, is subtitled A Photo Essay on the Odyssey of Identity in New Orleans. It’s about the nature of creativity in the Crescent City, which seems to have a lot to do not just with the whims and brainstorms of young creatives but more importantly with the ways that the past weaves into the present and the future. In other words: History lives.

Compared to Portland, which “shares much of the same liberal spirit,” Harvey says:

… the Crescent City seems more enamored by cultural movements than the rabid individuals who create them. I was charmed by the willingness of New Orleanians to not only give sanctuary to the expressive oddball, but to provide a platform for their development.

Like Oaxaca, New Orleans has a deep and long-running history with bones: See Harvey’s photograph below. Unlike Oregon, it seems to think that history has a place in the present and future.

*

PHOTOS, from top:

- Tom Fehrer, skulls, from “In the Navel of the Moon” at Camerwork Gallery, Portland.

- Stewart Harvey photographs skeletal revelry in New Orleans, at 23 Sandy Gallery in September.

Lots and lots of good writers will be showing up: Glad, for instance, to see that

Lots and lots of good writers will be showing up: Glad, for instance, to see that

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind.

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind. In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose

In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose  A person of my close acquaintance (all right, she’s my daughter) has been laid off from a job she detests — indeed, a job which for at least a couple of years she’s harbored elaborate fantasies of quitting in grand-tragedian style. They beat her to the punch. She outlasted many of her friends at this Dilbertian company, who, she says, have created a greeting for new members of the formerly-employed-by-idiots club.

A person of my close acquaintance (all right, she’s my daughter) has been laid off from a job she detests — indeed, a job which for at least a couple of years she’s harbored elaborate fantasies of quitting in grand-tragedian style. They beat her to the punch. She outlasted many of her friends at this Dilbertian company, who, she says, have created a greeting for new members of the formerly-employed-by-idiots club.