Sartre’s “No Exit” on the tilt, at Imago Theatre. Photo: Jerry Mouawad

Who wrote that play?

I don’t mean, did the modestly talented actor Will Shakespeare really write all those great stageworks, or was he just a convenient front man for Edward de Vere or some other dandy of the ruling class?

I mean, is the production you just saw actually of the play the playwright intended, or did it get reinvented so much in production that it actually became something else?

Charles Deemer has been gnawing on that bone as it relates to Jerry Mouawad’s critically praised production of Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit at Imago Theatre — a production that places the actors on an intricately balanced platform that shifts with every movement, echoing the tensions and balances among the characters.

Portland playwright Deemer first raised his objections in an Oct. 18 post on his blog, The Writing Life II. “Imago usually does original work, and brilliantly so,” he wrote. “It does original work here — it’s just misnamed. This production needs a little truth in advertising. It’s not Sartre. It’s variations on themes developed by Sartre. It’s interesting. It’s engaging. It just isn’t what the playwright intended and, as a playwright, I think this needs to be said.”

Deemer then followed up with comments on Martha Ullman West’s recent Art Scatter post about No Exit and a clutch of dance performances. “Composers do variations on a theme all the time and own up to it,” he wrote. “… What if someone went to the theater wanting to see the wonderfully grim original? What’s wrong with grim and cynical anyway?”

Then he added:

Let’s say a director resurrects Christmas at the Juniper Tavern and puts all the actors on roller skates because s/he believes it depicts the fluidity of their life journeys. Would I be amused? Guess.

“Edward Albee once closed down a production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf because George and Martha were presented as a gay couple.

“I once had the opportunity to ask Arthur Miller what he thought of an all-black version of Death of a Salesman that was done here with Tony Armstrong in the lead. ‘This is not the play I wrote,’ he told me.

“An advantage of the business of playwriting, as opposed to the business of screenwriting, is that playwrights retain ownership of their work. You legally can’t make changes without permission. Consequently I’ve long suspected that many, perhaps most, directors prefer their playwrights dead.”

Theater fans aren’t as volatile as opera fans, and it’s the rage these days in opera circles to boo directors and designers for undermining the music with conceptual approaches. Theater directors have been doing that for years (often, as Charles points out, with the work of dead playwrights who can’t fight back) and are lauded for it.

Interpretation is huge in the theater. But where does interpretation stop and something related but fundamentally different begin? Sometimes it seems like directors and designers use pre-existing works like especially fertile junkyards, discarding what they don’t want and mining them for treasure they can turn into something of their own. Novelists do that sort of thing all the time. But John Gardner didn’t call his book Beowulf. He called it Grendel.

What’s the essence of a play? Is it words? Is it tone? Is it the look of the thing? Or does it shift with every play, according to the play’s own core and elasticity? Putting the actors on roller skates for Christmas at the Juniper Tavern would absolutely change the play into something else. It MIGHT not irrevocably alter The Comedy of Errors.

Continue reading Whose play is it, anyway? On authors and interpreters

The festival’s Don Quixote is a world-premiere adaptation by the playwright

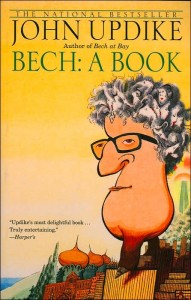

The festival’s Don Quixote is a world-premiere adaptation by the playwright  RABBIT’S AT REST.

RABBIT’S AT REST.