By Bob Hicks

It’s possible Mr. Scatter should have kept his mouth shut.

There he was, scanning the shelves at the local outlet of a mega-mega multinational book store, when a man and his son approached, trailing a clerk behind them. The boy looked to be 10 or 11, and he and his father had seen something on television about a new movie version of Gulliver’s Travels coming out later this month (Jack Black stars as a travel writer on assignment to Bermuda), and they thought it’d be fun to read the book before they saw the movie. But what version?

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

Having fulfilled her function, she walked away, never having mentioned that most adaptations also snip out big uncomfortable chunks of the text.

Father and son stood undecided, not sure whether to go for the condensed version or the real thing.

“Buy the original,” Mr. Scatter found himself saying. “It’s lots better.”

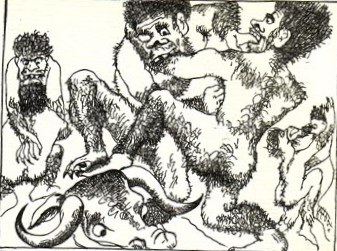

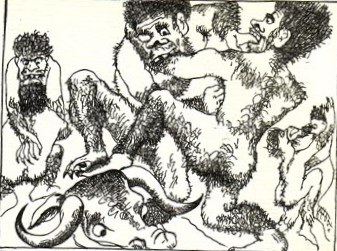

Well, it is. Jonathan Swift‘s novel, first published in 1726 under the title Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World, in Four Parts, by Lemuel Gulliver, first a surgeon, and then a captain of several ships, is one of the most hacked-at and sanitized books ever written, and those are the versions, unfortunately, in which most people encounter it. That seems to be largely because its fantastical elements (little people, giants, talking horses, flying cities) tilt it toward the catch-all of children’s literature, despite its often coarse detail and sophisticated adult themes. It is, underneath the flimsiest tissue of whimsy, a scabrous satire on European morals and politics, and quite rude on the subject of bodily functions, and such things will never do for the young and tender-cheeked. (Nor is it the only book to be hogtied and forcibly hustled into the children’s playpen in spite of its original intentions. It’s a bit of a jolt to remember that the Grimm folk and fairy tales, which have been so resolutely cleansed and prettified for nursery and adolescent consumption in the almost 200 years since the brothers first published them, were themselves sanitized versions of older, even more savage folk traditions.) In brief: Take out the scruffy parts of Gulliver’s Travels and you’ve ripped out its heart and soul.

Continue reading Gulliver’s Travels, unbowdlerized →

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”

“You probably want one of the adaptations,” the clerk said helpfully. “The language is modernized, and they’re a lot easier for kids to read than the original.”