10:10 p.m., this joint is emptying out.

10:10 p.m., this joint is emptying out.

I think they want to kick us out.

A couple of things first:

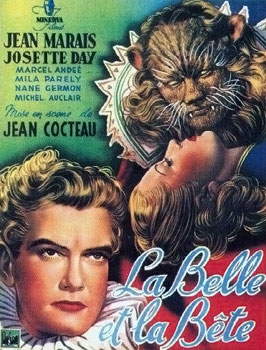

In the film that Glass adapted, Cocteau was revitalizing the “fairy tale,” which even in the 1940s and 1950s had been relegated to the children’s shelf, and giving it back its spirituality and wonder. He was after the source of power in the universe. And, yes, it seems to have something to do with love. Maybe the Beatles were right. Or Jesus. Or whoever. Why is it these questions are usually left to “kids” tales?

No rock ‘n’ roll Glass in Orphee. This is beautifully crafted, and beautifully orchestrated, music, with some gorgeous vocal lines, and the singers’ volume got better as the evening progressed.

And it was ACTED — no Fat Lady planting her feet and belting here. Lisa Saffer as the Princess and Philip Cutlip as Orphee lead a truly good cast.

There’s mysticism here, folks: After a reference to “the one who gives the orders,” we’re told:

“Some believe he thinks of us. Others that we imagine him.”

And, of course, dry humor, as in this exchange between Orphee and a friend:

“The public loves me.”

“They are alone.”

This has been an odd way to write — fleetingly, conjecturally, without time to contemplate or shape. There’s much more to say, and quite a bit I did say that truly belongs on the cutting room floor. Well, too late. And too bad.

That’s all, folks, except for the bonus tracks below.

*****

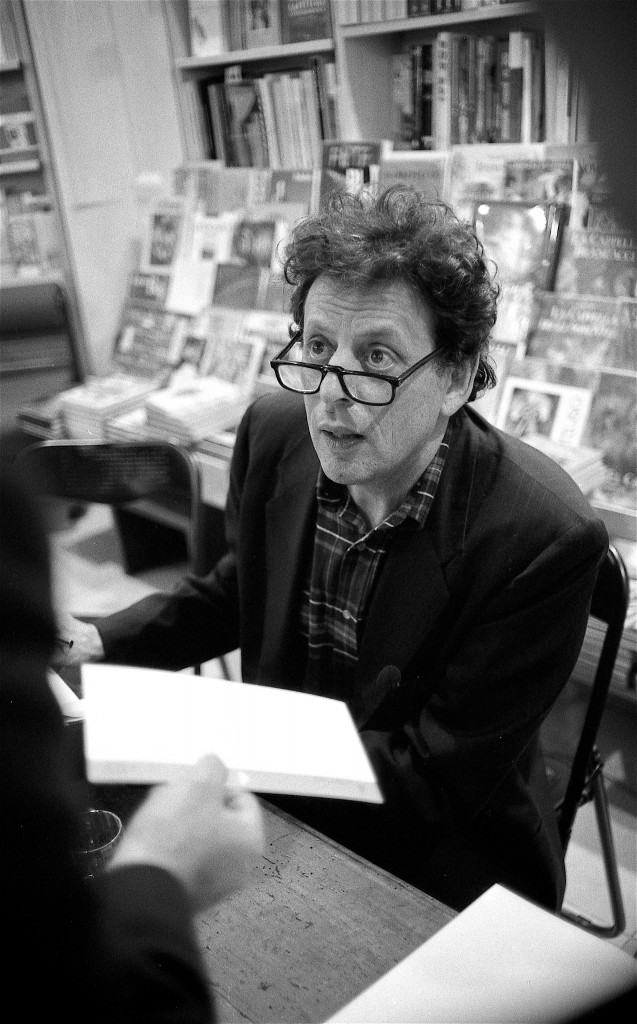

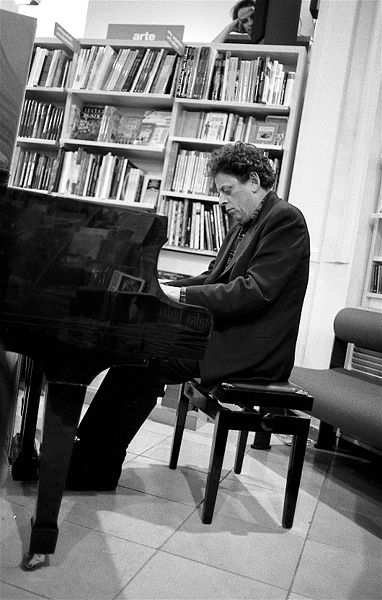

PHILIP GLASS BONUS TRACK #8

On NOT introducing himself to Cocteau in Paris in 1954, when the poet was living there and Glass had moved there for the first time. This was shortly after Cocteau and director Jean-Pierre Melville had collaborated on the movie version of Cocteau’s 1929 novel Les Enfants Terribles:

“I don’t think I could have. I think I would have been terrified of meeting him.”

*****

PHILIP GLASS BONUS TRACK #9

On today’s multimillion-dollar special effects and the way Cocteau did it in his films:

“I suppose Cocteau probably had a budget of five dollars and thirty-five cents for special effects. Yet those effects are magical.”

*****

xxxxxxx

Photo: Philip Glass in Florence, 1993. Pasquale Salerno/Wikimedia Commons