Mr. Scatter has been inside more theaters over the years than Hamlet’s father’s ghost, and he is sometimes haunted by what he sees — not the plays so much as the spaces themselves.

Actors are a hardy lot. Give ’em a script and they’ll perform almost anywhere, from pond-side amphitheaters (Classic Greek Theater of Oregon) to 100-degree attics (the old Chateau l’Bamm) to the sidewalks of New York (buskers of all sorts, from break-dancers to sword-swallowers to mimes).

There are barns and basements and back rooms. Old churches, old schoolhouses, old movie houses (the fabled Storefront Theatre once moved up in the world into a gritty ex-porn theater, scrubbing away most of the grime and soiled dreams but never quite nuking the cockroaches). Even, now and again, buildings actually built as legit theaters. As often as not, actors and designers are fighting the houses they play in, trying to turn the unlikely into the inevitable. Whole theories of performance have flourished based on the absence or presence of sophisticated theatrical technology.

Sometimes spaces that audiences love are disasters behind the scenes. The 350-seat bandbox that was the Main Stage at the old Portland Civic Theatre unfurled the chorus lines of musical comedies almost into the crowds’ laps, creating an exhilarating closeness that concealed multitudinous booby traps backstage. Audiences loved the intimacy of the old Black Swan at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. Actors who had to duck outdoors and race through the rain to make an entrance on the opposite side of the stage weren’t as thrilled.

A person develops favorites, spaces that somehow work for the kinds of theater presented in them. Spaces that have developed personality. Theaters need to be worked in, like a good pair of slippers. They need to develop their own memory-ghosts friendly and fearsome, and who is Mr. Scatter to deny the devout claims by some practitioners of the craft that a good theater must also have a resident cat?

A person develops favorites, spaces that somehow work for the kinds of theater presented in them. Spaces that have developed personality. Theaters need to be worked in, like a good pair of slippers. They need to develop their own memory-ghosts friendly and fearsome, and who is Mr. Scatter to deny the devout claims by some practitioners of the craft that a good theater must also have a resident cat?

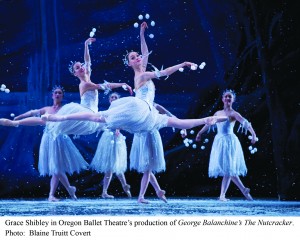

Some Broadway and West End houses have all of that, although I’m guessing about the cat. The grandly old-fashioned Maryinsky Theatre in St. Petersburg, Russia, home to what in the West is called the Kirov Ballet, is shabby and imperial and somehow blissfully outside the dictates of time. In Ashland, the Angus Bowmer Theatre and the New Theatre, which replaced the Black Swan as the festival’s black-box space, are extraordinary theatrical machines that work for audiences and performers alike. The Stephen Joseph Theatre, Alan Ayckbourn’s home space in Scarborough, England, is the house that farce built (or maybe the house that built farce). At the Joyce Theatre in New York, all sorts of dance explode from the stage. San Francisco’s original Magic Theatre was more a verb than a noun. The original Empty Space in Seattle, a rickety third-floor walkup hard by the freeway, exuded adventure and discovery.

In Portland, I like the stripped-down intimacy of CoHo Theater, although I avoid the cramped back-row seats, which can crack your knees like they’re wishbones dried in the oven. I’m less fond than a lot of people of Portland Center Stage’s rehab of the old armory building — its industrial-chic public spaces seem a bit self-conscious to me, and I wonder how well they’ll wear — but I love how the building has become a genuine public gathering spot, inviting and important even beyond its main purpose of providing a space for shows. The Dolores Winningstad Theatre, when it’s used right (for budgetary reasons, it rarely is) can be terrific.

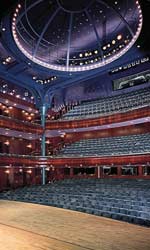

The Newmark, the Winnie’s bigger sister at the Portland Center for the Performing Arts, is sometimes slagged for the distance of its stage, the dryness of its sound, and the nosebleed pitch of its upper balcony. But it feels luxuriant, like a special place for a special occasion, and audiences love it. It re-creates the old-fashioned sense that a theater is someplace out of the ordinary — and that, I’ll argue, is a good thing for a city to preserve in at least a few of its performance spaces.

The Newmark, the Winnie’s bigger sister at the Portland Center for the Performing Arts, is sometimes slagged for the distance of its stage, the dryness of its sound, and the nosebleed pitch of its upper balcony. But it feels luxuriant, like a special place for a special occasion, and audiences love it. It re-creates the old-fashioned sense that a theater is someplace out of the ordinary — and that, I’ll argue, is a good thing for a city to preserve in at least a few of its performance spaces.

So imagine how Mr. and Mrs. Scatter felt, a week ago Friday, when they arrived at Artists Repertory Theatre for the opening-night performance of Holidazed, the seasonal comedy by Mark Acito and C.S. Whitcomb. We happened to enter through the Morrison Street lobby, which is a city block and a cascade of stairs above the Alder Street level, where the play was being performed.

The stairs are new. They tie together the two buildings that make up the Artists Rep complex, which sits on a hillside and includes two similar intimate performance spaces, both in three-quarter thrust configuration. The theaters’ size and shape — seating is on a sharp rake, so even the highest seats are close enough to the stage that you can see the sweat on the performers’ upper lips — create the company’s style, which is in-your-face intimacy, with an overlay of white-collar comfort.

Artists Rep has grown slowly and cautiously: It started as a loose actors’ collective in a little upstairs space at the downtown YWCA, and moved with baby steps once it switched its home to what’s now called the West End of downtown, on the west side of the I-405 freeway and within easy yodeling distance of downtown proper, the Pearl District, and old Northwest. Over many years and a few relatively quiet campaigns the company’s expanded and improved its holdings, buying its original space on Alder and adding the Portland Opera’s old headquarters above it on Morrison when the opera moved into its own building near the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry on the east bank of the Willamette River.

The second building expanded the company’s space to a remarkable 89,000 square feet — a huge amount of real estate for a company of Artists Rep’s size and budget. It allowed the construction of a second stage, which sometimes houses Artists Rep productions and sometimes is rented out to other companies. And it gave Artists Rep ample space to gather its scenic and costume shops and its office and rehearsal spaces in the same complex.

But the two buildings always felt like two buildings — until now. Walking through the buzz of the upstairs lobby and looking down the stairwell into the Alder Street lobby below was a startling and heart-leaping experience. All of a sudden, little Artists Rep seemed grown up. The new stairwell — designed by the Portland firm Opsis Architecture, which has been working with Artists Rep through several phases of its expansion — takes what was two things and fuses them into a single, lavishly flowing building.

But the two buildings always felt like two buildings — until now. Walking through the buzz of the upstairs lobby and looking down the stairwell into the Alder Street lobby below was a startling and heart-leaping experience. All of a sudden, little Artists Rep seemed grown up. The new stairwell — designed by the Portland firm Opsis Architecture, which has been working with Artists Rep through several phases of its expansion — takes what was two things and fuses them into a single, lavishly flowing building.

The photos at top and right give a sense of the skeleton of the united building but not of the way it comes alive when the theaters are in use and two sets of audience are milling about, laughing and gazing and murmuring the way excited groups of people do. The new space (an elevator will be added when finances allow) shoots sound up and down the stairwell, which has the accelerating quality of white-water rapids on a mountain stream. The old cramped Alder lobby is now unfettered, expanded in space and imagination, linking in creative ways to the action in the Morrison lobby upstairs. Suddenly theatergoers are in a space not just to scrunch their shoulders together and wait, but a space where something’s happening.

That’s exciting. And that excitement is bound to have a spillover to the upstairs and downstairs stages themselves (which, in case you’re worried, are well-insulated against the racket in the common spaces). What strange and wonderful ghosts are waiting to be created here?

***************

PHOTOS, from top:

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected:

The news today isn’t good, and it isn’t unexpected:  On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian,

On a lighter note, a trip to North Portland for a puppet show got me thinking about the great ecdysiast Gypsy Rose Lee, she of the most celebrated stage mom in show business. (That would be Momma Rose, in the musical Gypsy.) You can see the results of my puppet adventures, as related in Monday’s Oregonian,