“In my opinion a museum cannot and should not be showing only art by dead people.”

Lee Musgrave was sitting in his little ground-floor office at the Maryhill Museum of Art, away from the sweeping view just outside of the Columbia River Gorge and the eastern face of Mt. Hood. He’d just told me that after 14 years as the museum’s only curator he was getting ready to retire — he leaves at the end of July — and he was in a relaxed, expansive mood.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8.

But then, I was also curious to see the newest incarnation on the museum grounds of Musgrave’s annual outdoor-sculpture invitational, Maryhill’s lively contemporary response to its historic collection of Rodin sculptures in the indoor galleries. And if this quirky, oddly intoxicating little museum hadn’t begun to pay much more serious attention to the contemporary world in the past couple of decades, I might have just left it dozing away in the desert and never gone visiting at all.

These days, I consider it a personal requirement to drive to Maryhill at least once a year, and I freely confess that although I find the museum an intriguing place — I can’t think of any institution anywhere else, even in the wild-and-woolly West that it so quintessentially represents, that’s quite like it — a lot of the allure is simply that it offers a great excuse to make one of the most drop-dead gorgeous drives in the United States. The improbable fortress that is Maryhill, perched high on a cliff in that stretch east of The Dalles where forest has given way to desert, is the end-of-the-road payoff to a journey that’s already been its own reward.

“In my time here,” said Musgrave, who on the day of my visit was in a genial summing-up mood, “I’ve done 59 contemporary shows and exhibited the work of 258 Northwest artists.”

Those figures might come as a surprise to people who tend to think of Maryhill in response to its historical collections, an assembly of oddments that make it seem a little like a far-west cubby-hole annex to the Smithsonian Institution, “America’s Attic.” There are the chess sets, the Russian icons, the Rodin plasters, the old weapons, a good Native American collection, the road plans of visionary engineer and rural utopian Sam Hill, memorabilia of the turn-of-the-century dance sensation Loie Fuller, the Queen of Romania’s furniture, the peacocks strutting around the grounds (they scare away snakes), the nearby concrete replica of Stonehenge, the French high-fashion dioramas of Theatre de la Mode.

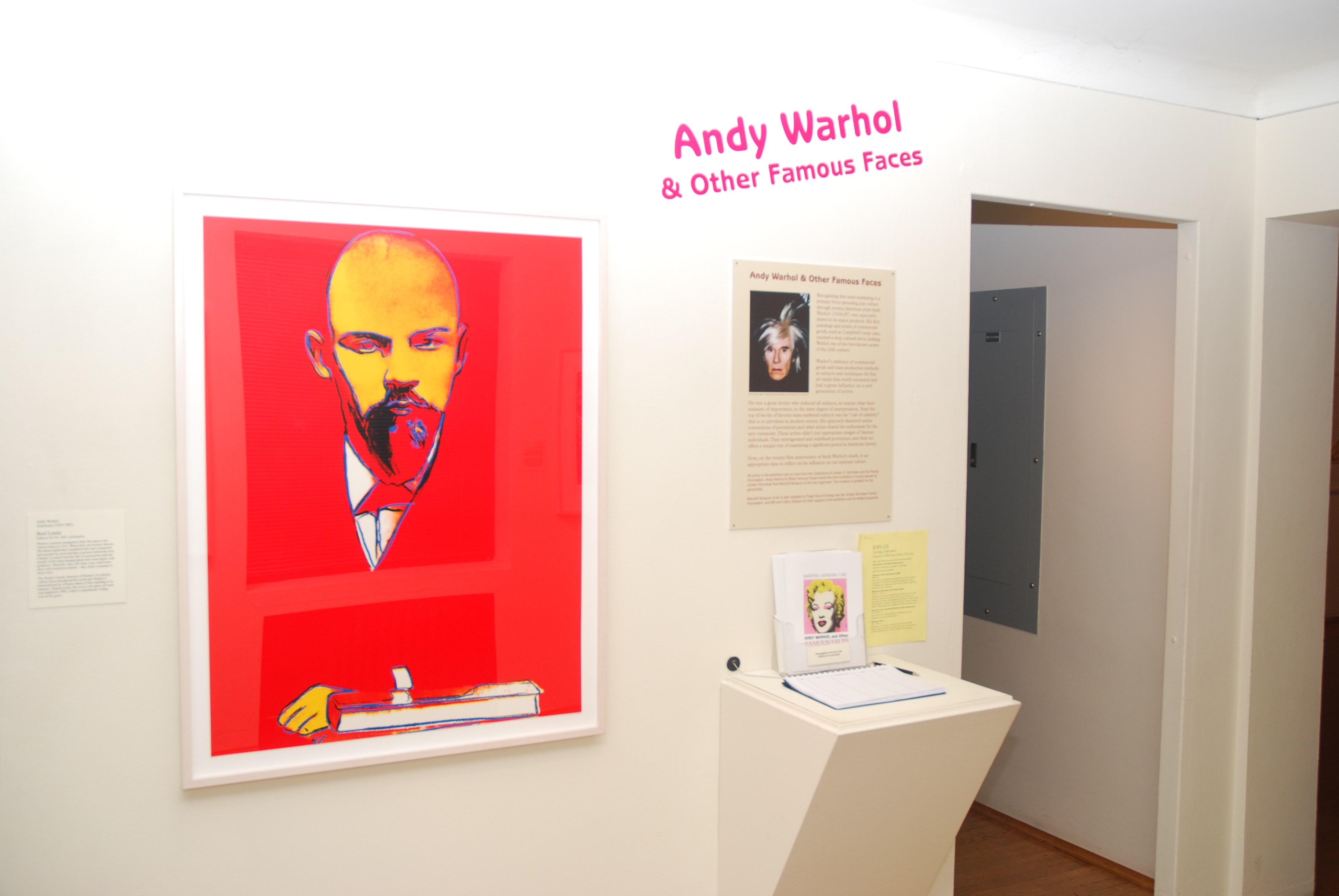

But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

The annual outdoor sculpture show is a good example of how Musgrave’s connections with contemporary artists have influenced what the museum does. On his first day on the job in 1995, he says, he told his new co-workers, “I can’t believe you’ve got 6,000 acres and no sculpture outside.” So he started the sculpture program.

Continue reading Columbia River School: The art landscape in the Gorge