Go to him now, he calls you, you can’t refuse

When you got nothing, you got nothing to lose

You’re invisible now, you got no secrets

To conceal.

Bob Dylan, “Like a Rolling Stoneâ€

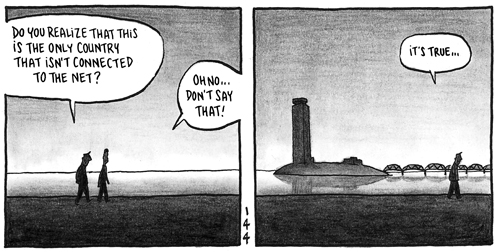

Ubiquitous means being or existing everywhere at once. A novel word for a commonplace idea. We now accept the idea that surveillance is ubiquitous, even though we commonly, and romantically, associate it with the world of stealth and spying, as in popular novels and movies of the James Bond or Jason Bourne variety.

Its reach is much broader than that.

I posted on CIA, surveillance and paranoia the day before the revelation that “contract†employees at the State Department accessed the passport files of Barack Obama and other presidential candidates. “Contracting†of course means “outsourcing,†which means the likes of Blackwater and Halliburton and its subsidiaries, the client states of administration officials and lobbyists. The State Department claims it was simply innocent curiosity – before they’ve even investigated. And little chance we’ll see the results of the investigation soon. It is essentially the same claim made on behalf of the Patriot Act. Communication surveillance is directed at terrorists; honest Americans have nothing to fear. I don’t “fear†anything, but I have no illusions. If information is there to mine, the roving political operatives in either party will mine and exploit it for political purposes.

Surveillance is pervasive. I recently ran the 2008 Portland Shamrock Run and a few days later received an email with a photo of me captured mid-race (and laboring mightily) that I can purchase for a fee. I can’t reproduce the photo here without violating intellectual property laws (as if I’d want that hunkered huffer-puffer figured-forth in this space). I assume the photographer was able to identify me by the timing chip I wore on my ankle. I don’t recall that I gave race officials permission to use me commercially in this way, but I imagine it is there somewhere in the entry form fine print. This is likely as “innocent†as surveillance gets. Cameras are everywhere and we now have the capability if not the political will or federal funding to create virtual borders. It is not, finally, that we are being tracked. It is that we are now effectively captive to technology and the paranoid will to use it in order to maintain political order.

Continue reading Surveillance: From Barbed Wire to the Invisible Prison

A week ago, I sat in on a lecture by Roger Martin,

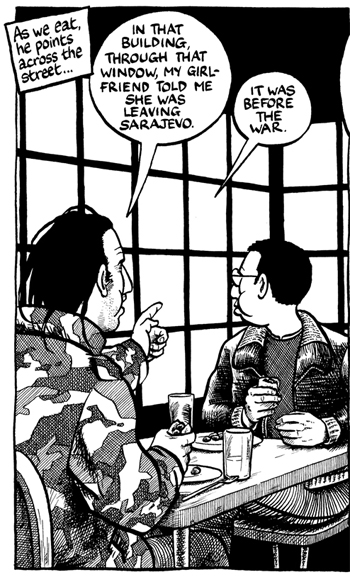

A week ago, I sat in on a lecture by Roger Martin,  That’s Joe Sacco, to the right, looking out of the window in a restaurant in the old part of Sarajevo. As usual he is passive — listening to the stories that other people tell him, observing life around him and presumably taking notes, though in this frame, he doesn’t seem to have a notebook with him. He looks a lot like a — journalist. Oh. There’s no drawing pad, either. And that’s what usually separates him from other journalists: He is recording conversations,

That’s Joe Sacco, to the right, looking out of the window in a restaurant in the old part of Sarajevo. As usual he is passive — listening to the stories that other people tell him, observing life around him and presumably taking notes, though in this frame, he doesn’t seem to have a notebook with him. He looks a lot like a — journalist. Oh. There’s no drawing pad, either. And that’s what usually separates him from other journalists: He is recording conversations, The rhyme is after

The rhyme is after