Tonight is the gala Dance United in Portland, the all-star benefit to help get financially ailing Oregon Ballet Theatre out of its fiscal sinkhole, and under any other circumstances I would be there with bells, cheering the dancers on.

But on Wednesday the large smelly boys were paroled from a nine-month sentence in the Portland public school system, and Mrs. Scatter and I had a longstanding deal to whisk them to the Oregon coast to the four-way-split shared getaway we’ve been holding in our own tenuous economic grasp for close to 20 years. And on that subject, just one question: What sort of fool would pay actual money for a share of a piece of property in the shadow of a place called Cape Foulweather?

But on Wednesday the large smelly boys were paroled from a nine-month sentence in the Portland public school system, and Mrs. Scatter and I had a longstanding deal to whisk them to the Oregon coast to the four-way-split shared getaway we’ve been holding in our own tenuous economic grasp for close to 20 years. And on that subject, just one question: What sort of fool would pay actual money for a share of a piece of property in the shadow of a place called Cape Foulweather?

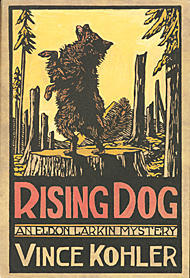

So here I sit, staring at the oddly quiescent cape (the sun is out, sort of), with a copy of Vince Kohler‘s Eldon Larkin mystery Rising Dog at hand, thinking about this shaggy stretch of oceanfront I’ve come to love. Not that I get out here very often. Regular readers may recall this post about Vince, a kind of forgotten hero of Oregon literature, and his shambling news-hound hero, Eldon, as introduced in the first Larkin mystery, Rainy North Woods.

Rising Dog (the title comes from the curious case of a mutt that’s been run down by a 14-wheeler on busy U.S. 101 and then seems to have risen from the dead) came in 1992, and like the late and lamented Mr. Kohler’s other mysteries, it really ought to be better-known.

Eldon’s stretch of the Oregon Coast, though mythical (there is no actual Nekaemas County), runs south of these parts, nearer Coos Bay territory, where life is less touristy and more hardscrabble, although Newport this week seems in desperate want of those recently disappearing city spenders. Wall Street has not been kind to small towns that rely on the whims of visitors.

Still, I feel I must pass on this description of life in the mythical Port Jerome on a rare day when the rains have ceased and the sun has come a-wandering in:

“The sun had drawn the town’s population from hiding. That was the worst thing about good weather. In the streets were women fifty to eighty pounds overweight, squeezed into blue jeans or blue or white knit polyester slacks. There were stringy, hard-faced men in grubby denims and crushed, grimy baseball caps. There were potbellied salesmen with long sideburns and lined, pouchy faces, and adolescents reveling unaware in their brief season of physical beauty before declining into the sleazy hardness of their elders.”

As I sit here I am wearing a pair of aged, faded jeans, gone stringy at the cuffs and with a hole in the pocket that encourages a trickle-down theory of fugitive pens and pennies. I have on a faded purple T-shirt, a little spongy at the collar, and a gray sweatshirt that is unaccountably my favorite piece of upper-body wear. My “Mo’s West” baseball cap, bearing the emblem of a favored chowder shack, is flung casually close to hand. I make no claims or excuses for the lazy paunch floating beneath my belt. My socks are semi-clean, and my hair has taken on that wild dry look of straw that’s been electrocuted in a summer storm. It does no good to brush or comb it. It’s gone native, and it ain’t comin’ back, not as long as I’m within spitting distance of the ocean. In certain ways, once a small-town boy, always a small-town boy.

Vince meant that description of coastal folk ruefully, but with a certain affection. Eldon’s no Adonis himself. I saw the Adonises, six of them, yesterday, in their black rubber bodysuits, drifting out from the beach by Otter Rock on their surf boards. I’m guessing none of them was a logger or a commercial fisherman or one of those incredible samurai-skilled women who so swiftly gut and clean the salmon and halibut coming in from the tourist fishing-excursion boats to the docks on the Newport waterfront.

One more thing I can’t resist passing along: Vince’s not-so-standard legal disclaimer from the beginning of the book:

Rising Dog is a work of fiction. The novel’s characters inhabit a stretch of the southern Oregon coast that is entirely a product of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to people, places, or institutions in the real world is an enormous and shocking coincidence. In particular, the Sons of Eiden Hall and its denizens are not intended to represent any actual Scandinavian group.

Skoal to all that.

So one day last week I picked up my old copy of

So one day last week I picked up my old copy of  Perhaps if the poetry cards go away, riders could start carrying around books of poetry — reading them, exchanging them, passing them around. TriMet could have stacks of books on the bus, donated by riders, free for the taking and dropping off again.

Perhaps if the poetry cards go away, riders could start carrying around books of poetry — reading them, exchanging them, passing them around. TriMet could have stacks of books on the bus, donated by riders, free for the taking and dropping off again.

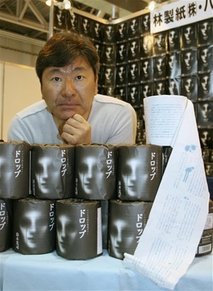

Books come in all shapes and sizes and perform all sorts of functions, in addition to acting as containment vessel for reading “matter.†And almost anything can function as bathroom reading. Where else memorize your credit card numbers? Now, it turns out, almost everything is worth the paper it’s printed on.

Books come in all shapes and sizes and perform all sorts of functions, in addition to acting as containment vessel for reading “matter.†And almost anything can function as bathroom reading. Where else memorize your credit card numbers? Now, it turns out, almost everything is worth the paper it’s printed on.

Painting is reading is gardening. Weeds everywhere.

Painting is reading is gardening. Weeds everywhere. Art Scatter feels a bit like Cole Porter’s

Art Scatter feels a bit like Cole Porter’s  Today I plucked

Today I plucked

As anthologies go, the monstrous Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: The University of California Book of Romantic and Postromantic Poetry (2009), edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey Robinson, is a Hummer pretending to be a hybrid. Combined with its sturdy predecessors, Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern and Postmodern Poetry, Volume One: From Fin-de-Siecle to Negritude (1996), and Volume Two: From Postwar to Millennium (1998), edited by Rothenberg and Pierre Joris, with 2600 combined pages, they are a fully-loaded triple trailer.

As anthologies go, the monstrous Poems for the Millennium, Volume Three: The University of California Book of Romantic and Postromantic Poetry (2009), edited by Jerome Rothenberg and Jeffrey Robinson, is a Hummer pretending to be a hybrid. Combined with its sturdy predecessors, Poems for the Millennium: The University of California Book of Modern and Postmodern Poetry, Volume One: From Fin-de-Siecle to Negritude (1996), and Volume Two: From Postwar to Millennium (1998), edited by Rothenberg and Pierre Joris, with 2600 combined pages, they are a fully-loaded triple trailer. It’s a great idea, and it’s hers, and no way am I going to steal it, because that would be so wrong. But just this once I’m going to borrow it, because after putting new shelves in the office I’ve been restocking some books that have been sitting in boxes in the basement, and that includes pretty much my entire collection of mysteries, which I’ve now been taking out selectively and re-reading with pleasure.

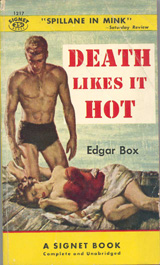

It’s a great idea, and it’s hers, and no way am I going to steal it, because that would be so wrong. But just this once I’m going to borrow it, because after putting new shelves in the office I’ve been restocking some books that have been sitting in boxes in the basement, and that includes pretty much my entire collection of mysteries, which I’ve now been taking out selectively and re-reading with pleasure.

Yes, charmed. And I thought, this is policymaking outside the channels of policy. Here, in Obama, is a man utterly at ease inside his own skin. That’s why people respond to him. Because he’s comfortable with himself.

Yes, charmed. And I thought, this is policymaking outside the channels of policy. Here, in Obama, is a man utterly at ease inside his own skin. That’s why people respond to him. Because he’s comfortable with himself.