The coolest thing about the boffo reviews for the new Australian production of Long Day’s Journey into Night is that it gives Mr. Scatter the chance to type the word “boffo.”

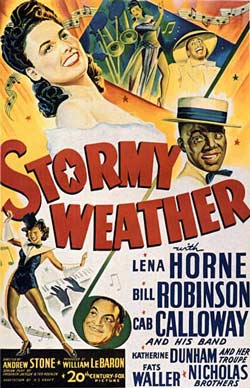

Boffo. There it is. He loves that word. It makes him feel so, so … Variety-ish. As in, “Sticks Nix Hick Pix” (improved to the more rat-a-tat “Stix Nix Hix Pix” in the 1942 movie musical Yankee Doodle Dandy.) Please hand Mr. Scatter his wide-brimmed hat with the “Press” card sticking out from the band. He’ll spring for drinks, giggles and gossip at the Cocoanut Grove if you’ll bring him the lowdown for his next juicy Hollywoodland scoop. Wait: Is that Gloria Swanson in the next booth?

Boffo. There it is. He loves that word. It makes him feel so, so … Variety-ish. As in, “Sticks Nix Hick Pix” (improved to the more rat-a-tat “Stix Nix Hix Pix” in the 1942 movie musical Yankee Doodle Dandy.) Please hand Mr. Scatter his wide-brimmed hat with the “Press” card sticking out from the band. He’ll spring for drinks, giggles and gossip at the Cocoanut Grove if you’ll bring him the lowdown for his next juicy Hollywoodland scoop. Wait: Is that Gloria Swanson in the next booth?

In brief: Sydney Theatre Company‘s production of Eugene O’Neill’s harrowing masterpiece has been knocking ’em dead Down Under, as critic John McCallum writes in The Australian. Starring William Hurt, Robyn Nevin, Luke Mullins and Portlander Todd Van Voris, it’s a co-production with Portland’s Artists Repertory Theatre. It continues in Sydney through Aug. 1, then comes stateside for its run at Artists Rep Aug. 13-29.

Praising the cast across the board, McCallum calls it “a stunning, absorbing production, full of emotional complexity.” Here’s what he has to say about Van Voris, who plays the sozzled son Jamie:

“Van Voris’s Jamie, rotund and strutting self-confidently at first, has degenerated into an alcoholic wreck by the time he returns at the end from the bars and whorehouses to which he has tried to escape. In a powerful long scene he drunkenly reveals something of his scary true nature. But here too, as well as the hate and selfishness, we can see the love underneath, a love that he has been so assiduously trying to drown in whisky for so long.”

Of more than passing interest: Artists Rep will follow up on Long Day’s Journey with a new production of the rarely revived Ah, Wilderness!, a warmly nostalgic play that’s the closest O’Neill ever came to writing a flat-out comedy. It’ll run Sept. 7-Oct. 10.

Boffo. Boffo. Boffo.

Mr. Scatter just can’t help himself.

*

PICTURED: The cast of “Long Day’s Journey Into Night,” from left: William Hurt, Todd Van Voris, Robyn Nevin, Luke Mullins. Photo: Jez Smith

Glass decided he liked the Portland cast so much that it should be recorded, leading to a double first: Portland Opera’s first-ever commercial recording, and the first full recording of Orphee, part of a Cocteau trilogy by Glass that also includes La Belle et la Bete and Les Enfants Terribles.

Glass decided he liked the Portland cast so much that it should be recorded, leading to a double first: Portland Opera’s first-ever commercial recording, and the first full recording of Orphee, part of a Cocteau trilogy by Glass that also includes La Belle et la Bete and Les Enfants Terribles. Used to be things were winding down by the time you reached the summer solstice, and there definitely was a time when addicts like me found it impossible to get any kind of movement fix once the Rose Festival was over. Not this year — I actually had to make choices, not having managed the art of being in two or three places at once. So to several emerging choreographers as well as some much more established ones, I apologize for not making it to their performances and herewith offer some thoughts on those I did see.

Used to be things were winding down by the time you reached the summer solstice, and there definitely was a time when addicts like me found it impossible to get any kind of movement fix once the Rose Festival was over. Not this year — I actually had to make choices, not having managed the art of being in two or three places at once. So to several emerging choreographers as well as some much more established ones, I apologize for not making it to their performances and herewith offer some thoughts on those I did see. No, we’re talking about theater awards season. The

No, we’re talking about theater awards season. The  This time he was working, covering the event for The Oregonian, and it turned out to be remarkable — well worth twisting and ducking twelve blocks through the crowds and police blockades for the Rose Festival’s

This time he was working, covering the event for The Oregonian, and it turned out to be remarkable — well worth twisting and ducking twelve blocks through the crowds and police blockades for the Rose Festival’s  Heald, the Broadway and Hollywood vet who gave it up to move to Ashland and join the acting company at the

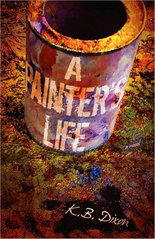

Heald, the Broadway and Hollywood vet who gave it up to move to Ashland and join the acting company at the  Between epic motorcycle trips and learned sessions with master brewers, Foyston’s been known to paint up a modest storm of his own. And Ken Dixon, who in the great long-ago wrote an occasional witty and perceptive art review for Mr. Scatter at a Large and Important Daily Publication, is a writer with a singular miniaturist approach to the puzzle of the written word. His books are wry and elegant, carefully measured for precise effect, and they maintain a sly satiric distance. At a time when the art world sometimes seems nearly strangled in a tangle of theory and jargon, even the name of Dixon’s artist-hero seems perfectly chosen: Christopher Freeze.

Between epic motorcycle trips and learned sessions with master brewers, Foyston’s been known to paint up a modest storm of his own. And Ken Dixon, who in the great long-ago wrote an occasional witty and perceptive art review for Mr. Scatter at a Large and Important Daily Publication, is a writer with a singular miniaturist approach to the puzzle of the written word. His books are wry and elegant, carefully measured for precise effect, and they maintain a sly satiric distance. At a time when the art world sometimes seems nearly strangled in a tangle of theory and jargon, even the name of Dixon’s artist-hero seems perfectly chosen: Christopher Freeze.

Both works, as the

Both works, as the  Austen’s comedies may be the most precise and practical romances ever written. Obsessed with the often foolishly claustrophobic concerns of a narrow slice of self-satisfied society, they’re also worldly. Within the confines of that small society she discovers a measured universe of human possibility, from the perfidious to the noble. And she does it with one of the slyest, keenest raised eyebrows in all of literature.

Austen’s comedies may be the most precise and practical romances ever written. Obsessed with the often foolishly claustrophobic concerns of a narrow slice of self-satisfied society, they’re also worldly. Within the confines of that small society she discovers a measured universe of human possibility, from the perfidious to the noble. And she does it with one of the slyest, keenest raised eyebrows in all of literature.

Her daughter,

Her daughter,