In the past few months Art Scatter’s chief correspondent, Martha Ullman West, has been (as The New Yorker likes to say about its own correspondents) far-flung. We could tell you how much flinging she’s been up to, but it seems more appropriate to let her tell you herself. We will mention, however, that one of her flings was up the freeway to Seattle, where the national Dance Critics Association held its annual meeting and presented her with its Senior Critic’s Award, an honor that recognizes her position in the loftiest echelon of the profession. Congratulations, Martha, once again.

*

By Martha Ullman West

It’s a long time since I’ve made my presence known on Art Scatter (except to comment, lazy me). Since I last posted, on April 10, I’ve seen quite a lot of dancing, a Greek ruin or two or three, Maltese, Sicilian and Spanish museums, the Holy Grail (or not…), a clip aboard ship of the latest royal wedding extravaganza. I also received a prize, for which I had to give a lecture, and that little task made me think about all of the above and more.

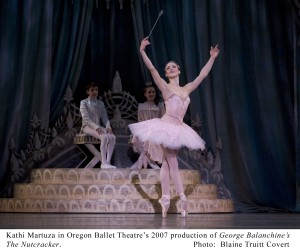

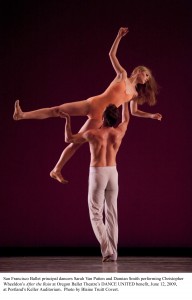

Just before I skipped town on April 23, I witnessed Anne Mueller dance ballet for the last time opening night of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s final show of the season, still at the top of her form, showing her range in Trey McIntyre’s funky Speak, Nicolo Fonte’s Left Unsaid, and Christopher Stowell’s Eyes on You. More down the line about the opening ballet in that program, Balanchine’s Square Dance, which I also saw New York City Ballet perform in May.

Earlier in the week, at Da Vinci Middle School’s spring concert, a motley batch of middle school-age boys, seven of them, performed, identifiably, Gregg Bielemeier’s idiosyncratic juxtaposition of small precise movement and space-eating choreography, improvising within the form. At an age when going with the flow ain’t a goin’ to happen, they did just that, and it was lovely to see.

And then I was off on a cruise of what was originally supposed to be the Barbary Coast and include Tunisia, where I’ve long wanted to go, but world events interfered so Sardinia and Menorca were substituted, as well as extra time in Valencia, where in addition to one of the Holy Grails (housed in the cathedral there) we saw a parade in traditional garb — little girls in ruffled dresses and mantillas, elderly gents trying to manage their swords — and after that, in Granada, the magical Alhambra. That’s a place I’ve wanted to see with mine own eyes since my father rendered in paint how he imagined it looked in the Middle Ages.

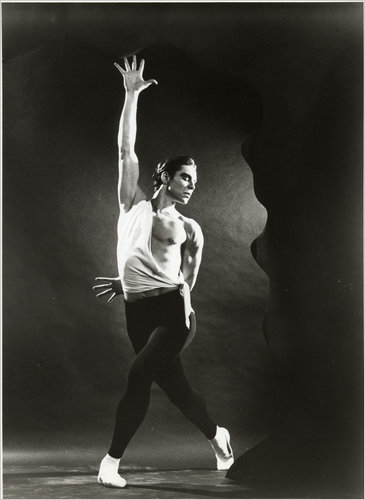

Few dancers are as capable of eloquence with words as they are with their bodies, but there are exceptions. Jacques d’Amboise, one of this country’s first homegrown great male ballet dancers, is one of them, and he’ll be in town to talk about his new book,

Few dancers are as capable of eloquence with words as they are with their bodies, but there are exceptions. Jacques d’Amboise, one of this country’s first homegrown great male ballet dancers, is one of them, and he’ll be in town to talk about his new book,

The worst performance shall come first: an unspeakably godawful belly dance demonstration on board the Nile River boat on which I spent four otherwise glorious nights.

The worst performance shall come first: an unspeakably godawful belly dance demonstration on board the Nile River boat on which I spent four otherwise glorious nights. Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans.

Really, it was a cross between a potlatch and an Obama rally, a gathering of the clans. The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process.

The Joffrey Ballet’s Aaron Rogers, performing Val Caniparoli’s Aria, recalled for me the profound pleasure of watching Val work with Portland dancers, first at OBT’s precursor Ballet Oregon, and then at OBT. Caniparoli’s kindness and courtesy in the studio turned out to be extremely productive when the company performed his Street Songs and other work. Rogers looked like he was enjoying himself, flirting with that mask, and certainly seduced the audience in the process. The bad doo-doo has just hit the fan. Art Scatter’s Barry Johnson, on his alternate-universe blog

The bad doo-doo has just hit the fan. Art Scatter’s Barry Johnson, on his alternate-universe blog

God knows Stravinsky’s 1912 Sacre du Printemps, played brilliantly here in its two-piano version by Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, is structured. Its lyrical beginning builds to a pounding crescendo in music that is still startling for its highly stylized brutality.

God knows Stravinsky’s 1912 Sacre du Printemps, played brilliantly here in its two-piano version by Carol Rich and Susan DeWitt Smith, is structured. Its lyrical beginning builds to a pounding crescendo in music that is still startling for its highly stylized brutality.