By Bob Hicks

Here’s the thing: If you’re an invading general with a roving eye, never invite a beautiful woman from the enemy city into your tent and then get so rip-roaring drunk you pass out.

Holofernes, this post’s for you.

Two intriguingly intertwined shows opened yesterday at the Portland Art Museum — The Bible Illustrated, maverick cartoonist R. Crumb‘s faithfully rendered graphic depiction of The Book of Genesis, and A Pioneering Collection: Master Drawings from the Crocker Art Museum, a gathering of almost 60 old-master drawings from the Sacramento museum’s impressive collections.

Friend of Scatter D.K. Row wrote vigorously in The Oregonian about Crumb’s project, and sometime in the next week or so the O will run my review of the Crocker exhibit. But first, let’s spend a little quality time with Holofernes, and Judith, and her faithful handmaiden, and one of our favorite Dutch artists, Hendrick Goltzius, an artist we admire so much we’ve featured him twice before: in this post about Hercules and baseball’s steroid scandal, and in this post about Wall Street’s bull and bear markets (we found his engraving of Icarus tumbling from the sky apropos).

In brief: Holofernes, a star general for the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, is laying siege to a city of the Israelites, and things are getting brutal. Alarmed and angry, Judith, an attractive young widow, sneaks out and into the enemy camp, where she charms Holofernes in his tent. She feeds him sweet cheeses, then gets him drunk as a skunk. While he’s sleeping it off she grabs his sword and lops off his head. When Holo’s army sees what’s happened it panics and heads for the hills. Judith saves the day!

In brief: Holofernes, a star general for the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezzar, is laying siege to a city of the Israelites, and things are getting brutal. Alarmed and angry, Judith, an attractive young widow, sneaks out and into the enemy camp, where she charms Holofernes in his tent. She feeds him sweet cheeses, then gets him drunk as a skunk. While he’s sleeping it off she grabs his sword and lops off his head. When Holo’s army sees what’s happened it panics and heads for the hills. Judith saves the day!

This story has fascinated artists for centuries, and everyone’s version seems singular. Why draw and paint pictorially? Because representational art tells stories, and there are as many different ways to tell a story as there are storytellers. Caravaggio, a genuine genius with a notorious violent streak, concentrated (inset) on the gorgeously bloody deed itself.

Goltzius chose a quieter approach. His study Judith with the Head of Holofernes (completed in the 1590s, about the same time as Caravaggio’s painting) is stylized and compositionally lovely, and you almost miss the horror of the scene. Goltzius offers the aftermath. He concentrates not on the violent act but on a moment of contemplation after. There: It’s done.

So many artists have tackled this tale that’s it’s hard to keep up with them. Here are a few of the sometimes wildly different versions they’ve produced:

*

Artemisia Gentileschi, the great early Baroque painter, must have had an especial affinity for this subject. The daughter of the successful Tuscan painter Orazio Gentileschi, she surpassed him but suffered deeply for her talent and for the great mistake she’d made by having been born a woman. She was raped by another painter; in the ensuing trial she was humiliated. Is it any wonder that Judith seemed a heroine to her, or that her own painting on the subject would be suffused with violence?

*

The Spaniard Francisco Goya‘s version is psychological and atmospheric, a dark and stormy image in which the victim, Holofernes, barely plays a role at all. The painting’s brusque and swift, as forceful and unrelenting as the act itself. Goya considers the horror and the moral implications of this heroic deed: Looking at Judith’s face, it’s hard not to wonder how this act will twist her soul. Her handmaiden, bent in prayer, must be wondering the same thing. One of the things I love about Goya is the way his intense theatricality plays like psychological realism.

The Spaniard Francisco Goya‘s version is psychological and atmospheric, a dark and stormy image in which the victim, Holofernes, barely plays a role at all. The painting’s brusque and swift, as forceful and unrelenting as the act itself. Goya considers the horror and the moral implications of this heroic deed: Looking at Judith’s face, it’s hard not to wonder how this act will twist her soul. Her handmaiden, bent in prayer, must be wondering the same thing. One of the things I love about Goya is the way his intense theatricality plays like psychological realism.

*

Painting a little bit before the others here (this one’s dated around 1530), Lucas Cranach the Elder gives us what seems the most oddball of images possible. There’s Holofernes’ head, all stylized and neatly grisly at the neck. There’s the sword, clean as a whistle (an odd saying: Don’t whistles go in people’s mouths?) And there’s Judith, dressed to the nines, feathered hat, bejeweled choker (in brilliant contrast to Holo’s severed neckline), looking like she’s ready for the Northern Renaissance version of the debutante ball. What’s going on? As the Met‘s Web site points out, the text (from the deuterocanonical Book of Judith, 10:4) reads in part that Judith was attired “so as to allure the eyes of all men that should see her.” And there you have her: the demure Northern Renaissance siren.

*

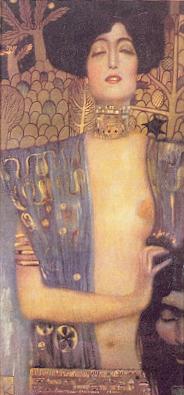

Gustav Klimt wasn’t the first painter to emphasize the sexual in the story of Judith and Holofernes. Way back in 1543, Jan Massys took advantage of the tale to paint a portrait of pert female nudity from the waist up. Four years later Hans Sebald Beham peeked a little lower, down to mid-thigh. (In both cases, the severed head is something of an afterthought). But with Klimt and his 1909 painting you see sexuality in spades. Judith is wearing the thinnest of peekaboo frocks, and her face wears an expression of intense arousal. Klimt’s heroine isn’t just doing something necessary to save her people: She’s getting off on it. The tie between sex and violence is explicit here. This may be a savage act. It’s also an act of pleasure. Too bad Holofernes didn’t get more out it.

Gustav Klimt wasn’t the first painter to emphasize the sexual in the story of Judith and Holofernes. Way back in 1543, Jan Massys took advantage of the tale to paint a portrait of pert female nudity from the waist up. Four years later Hans Sebald Beham peeked a little lower, down to mid-thigh. (In both cases, the severed head is something of an afterthought). But with Klimt and his 1909 painting you see sexuality in spades. Judith is wearing the thinnest of peekaboo frocks, and her face wears an expression of intense arousal. Klimt’s heroine isn’t just doing something necessary to save her people: She’s getting off on it. The tie between sex and violence is explicit here. This may be a savage act. It’s also an act of pleasure. Too bad Holofernes didn’t get more out it.

*

Finally, the German Symbolist Franz von Stuck‘s 1927 painting Judith und Holofernes seems to move the whole thing into that misty realm of myth. The two eternally linked actors are less characters than archetypes, dreams from the collective unconscious. Yet part of me sees something else here: Could this be the revenge of the artist’s model on the artist?

*

In the meantime, who is Judith, and what does she “mean”? All of these things, and more. Somewhere out there she strides in the company of Medea, and Bathsheba, and Salome, and Joan of Arc, and maybe even Queen Elizabeth I. The Spider Woman, the Avenging Angel, the Vampyr, the Temptress, the Savage Calculator, the National Hero, the Killer.

You heard what she said. Off with his head.

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

Hendrick Goltzius, Judith with the Head of Holofernes, n.d. Pen and dark brown ink, brush and grey wash and blue and white opaque watercolor, partially darkened, on brown laid paper, 20.3 x 16.6 cm. Crocker Art Museum, E. B. Crocker Collection 1871.142.

Caravaggio, “Judith Beheading Holofernes,” 1598-1599. Oil on canvas, 57 inches × 77 inches, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Rome. Wikimedia Commons.

Artemisia Gentileschi, “Judith Slaying Holofernes” (1614-20) Oil on canvas 199 x 162 cm Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence. Wikimedia Commons.

Francisco Goya, “Judith and Holofernes” (1819-23) 143.5 x 81.4 cm. Museo del Prado, Madrid. Wikimedia Commons.

Lucas Cranach the Elder, “Judith with the Head of Holofernes,” ca. 1530. Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History/The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons.

“Judith I,” by Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), painted in 1901. Oil on Canvas (84 x 32 cm) Österreichische Galerie, Vienna. Wikimedia Commons.

Franz von Stuck, “Judith und Holofernes,” 1927; 82 x 74 cm, Sammlung Heilmann, Munich. Wikimedia Commons.