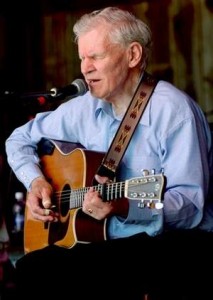

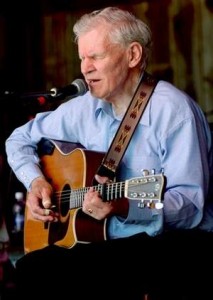

The inimitable Doc Watson died today at age 89. He was an American original, partly by being a true American traditionalist. I love his music and my idea, at least, of who he was. I wrote the following piece on him for The Oregonian, where it ran on June 1, 1997. I’d change a few things if I were writing it today, but it’s still worth a look if you knew Doc’s music, or if you didn’t but wish you had:

By Bob Hicks

On Father’s Day, the deep past visits Portland. And maybe, as popular music seeks a way out of its morass of superstardom, the future will too. Because try as we might to pretend it never happened, the past is part of us, and it shapes what we will be.

Thank goodness Doc Watson is helping to carry it.

Thank goodness Doc Watson is helping to carry it.

American music rarely sounds better than when Watson plays it. His easy-gliding voice is as fresh and sweet as the first bite of a mountain apple, and he is very likely the finest, most influential flat-top guitarist of his era.

He is, in short, a legend. But as far as popular musical consciousness goes, he is also, like the grand tradition of American optimism that he represents, in danger of fading away.

Semiretired since his son and partner Merle died in a tractor accident in 1985, Watson is about to make his first Portland appearance in eight years. On June 15, two days after opening this year’s Britt Festivals in Jacksonville, he’ll play a barbecue picnic at Oaks Amusement Park. And he will carry on his aging and unassuming shoulders the strength and possibilities of time itself.

At 74, Watson is a bridge back to the sounds and ideals from which we sprang: Irish-Scottish folk ballads, African-American field songs, Delta blues, mountain-fiddling tunes from Saturday-night dances and back-porch gatherings, age-old lullabies, church songs, Civil War stories, railroad songs, even Tin Pan Alley tunes and rockabilly.

Good music comes from someplace, and Watson’s is redolent of community — of people who share experiences, outlooks, territories. The specific someplace most important in the forming of his music is the Southern hill country that produced scratch farmers, cotton pickers, coal miners and string bands.

Continue reading R.I.P.: Doc Watson, American original →

Photo: Pak Han

Photo: Pak Han The most recent is

The most recent is  By Laura Grimes

By Laura Grimes Thank goodness Doc Watson is helping to carry it.

Thank goodness Doc Watson is helping to carry it. So he made a dance about it. His contemporary troupe

So he made a dance about it. His contemporary troupe  The grand theorizers tried by their creators and found wanting are the libertine Dr. Pangloss in Candide and the earnest schoolmaster Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times. You might find their viewpoints familiar.

The grand theorizers tried by their creators and found wanting are the libertine Dr. Pangloss in Candide and the earnest schoolmaster Thomas Gradgrind in Hard Times. You might find their viewpoints familiar.

Last weekend I saw three plays – the premiere of The Storm in the Barn at

Last weekend I saw three plays – the premiere of The Storm in the Barn at

I had fully intended to leave the Newmark Theatre at the second intermission Friday night, having watched many companies (well, three) perform a ballet I don’t think really works. But I was curious to see how convincingly Iino and Chauncey Parsons would de-classicize themselves in Val Caniparoli’s blending of tribal dance and ballet. In movement that is antithetical to classical epaulement, Iino was terrific, Parsons had the right energy, and Yang Zou’s undulating shoulders looked like they’d been oiled at the joint.

I had fully intended to leave the Newmark Theatre at the second intermission Friday night, having watched many companies (well, three) perform a ballet I don’t think really works. But I was curious to see how convincingly Iino and Chauncey Parsons would de-classicize themselves in Val Caniparoli’s blending of tribal dance and ballet. In movement that is antithetical to classical epaulement, Iino was terrific, Parsons had the right energy, and Yang Zou’s undulating shoulders looked like they’d been oiled at the joint.