The rhyme is after

The rhyme is after

all the repeated

insistence.

— Robert Creeley, “For W.C.W.â€

Black Mountain College, nestled in the mountains of eastern North Carolina, was small but thrived on its own terms for the 30 years it existed from the mid-1930s to mid-1950s. And thrives, perhaps, in memory because of the storied avant garde careers of teachers and students who took a turn there: Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Buckminster Fuller and Paul Goodman, as well as a cluster of poets that included Charles Olson, Robert Duncan, Denise Levertov and Robert Creeley (1926-2005). Creeley’s Selected Poems, 1945-2005 (University of California Press), edited by Benjamin Friedlander, has just been published, a microcosm of 60 years and some 60 volumes of work.

Creeley was inspired by jazz and abstract art and in fact collaborated with musicians, photographers and artists on various projects, a legacy of the communal atmosphere at Black Mountain. Creeley and other Black Mountain stalwarts were part of the “New American†poets anthologized by Donald Allen, but while they were associated with the Beats, they had their own clear path, a more reserved, austere form of verse that was innovative and experimental nonetheless.

One of my favorite Creeley poems is not included in Selected Poems, perhaps because it seems to be a shade romantic and sentimental. Here it is, “The Womanâ€:

I called her across the room,

could see that what she stood on

held her up, and now she came

as if she moved in time.

In time to what she moved,

her hands, her hair, her eyes, all things

by which I took her to be there

did come along.

It was not right or wrong

but signally despair, to be about

to speak to her

as if her substance shouted.

I read this poem in 1966 in a collection called For Love (1962),†and copied it out in my literary treasures notebook for Mrs. Wheeler’s senior English class. This was a different kind of love poem. No lips like cherries, cheeks like roses, hair like fine-spun gold – the verbal cornucopia that turned woman into an Acrimbaldo portrait. This was a real flesh and blood woman who stood across the room, held up, as it were, but not on a pedestal. The line break “what she stood on / held her up†still floors me. A simple, elegant poem, it tickles the mind and stirs the blood.

Continue reading Robert Creeley: “Selected Poems, 1945-2005” →

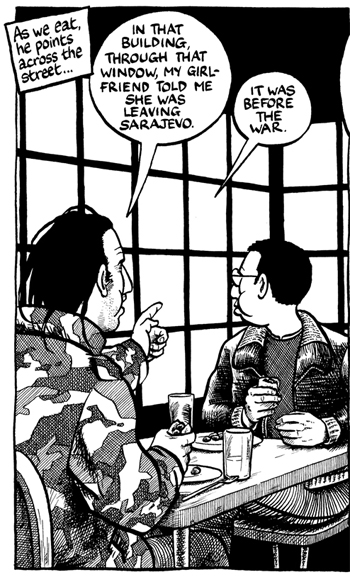

That’s Joe Sacco, to the right, looking out of the window in a restaurant in the old part of Sarajevo. As usual he is passive — listening to the stories that other people tell him, observing life around him and presumably taking notes, though in this frame, he doesn’t seem to have a notebook with him. He looks a lot like a — journalist. Oh. There’s no drawing pad, either. And that’s what usually separates him from other journalists: He is recording conversations,

That’s Joe Sacco, to the right, looking out of the window in a restaurant in the old part of Sarajevo. As usual he is passive — listening to the stories that other people tell him, observing life around him and presumably taking notes, though in this frame, he doesn’t seem to have a notebook with him. He looks a lot like a — journalist. Oh. There’s no drawing pad, either. And that’s what usually separates him from other journalists: He is recording conversations, The rhyme is after

The rhyme is after

Except that maybe we’ve read Blankets, and we’re pretty sure that Craig is not going to be able to give himself over to that sort of thing. And in fact, Craig is unhappy for a lot of Carnet. He counts the ways: he’s homesick, he misses his ex-girlfriend profoundly, she’s quite ill, he’s lonely, everything reminds him of her, he’s lonely, his hand hurts from so much drawing. Did we mention he’s lonely? His internal struggles spill out into the frames and pages of his notebook, enveloping them in fog of gloom. Morocco, near the beginning of the trip, is especially difficult, primarily because he doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t understand the culture very well and plunges into the worst melancholy of the trip.

Except that maybe we’ve read Blankets, and we’re pretty sure that Craig is not going to be able to give himself over to that sort of thing. And in fact, Craig is unhappy for a lot of Carnet. He counts the ways: he’s homesick, he misses his ex-girlfriend profoundly, she’s quite ill, he’s lonely, everything reminds him of her, he’s lonely, his hand hurts from so much drawing. Did we mention he’s lonely? His internal struggles spill out into the frames and pages of his notebook, enveloping them in fog of gloom. Morocco, near the beginning of the trip, is especially difficult, primarily because he doesn’t know anyone, doesn’t understand the culture very well and plunges into the worst melancholy of the trip.