By Bob Hicks

What’s been cooking lately in the Scatter kitchen? Well, a lovely baked dressing made up mostly of mushrooms, celery, onions and leftover bread slices (Mrs. Scatter’s clean-out-the-fridge creation). And another batch of baklazhannia ikra, or “poor man’s caviar,” an addictive eggplant/tomato/onion/pepper relish that William Grimes discovered recently in one of those great old Time/Life Foods of the World cookbooks and kindly passed along as a recipe in the New York Times.

Things have been cooking outside of World Headquarters, too. I’ve recently signed on as a regular contributor to Oregon Arts Watch, the ambitious online cultural newsmagazine masterminded and edited by my friend and former colleague at The Oregonian, Barry Johnson. I’ve filed a couple of pieces there already:

Things have been cooking outside of World Headquarters, too. I’ve recently signed on as a regular contributor to Oregon Arts Watch, the ambitious online cultural newsmagazine masterminded and edited by my friend and former colleague at The Oregonian, Barry Johnson. I’ve filed a couple of pieces there already:

- Portland’s dance renaissance and Eowyn Emerald’s pair of sold-out performances at BodyVox Dance Center.

- Edward Albee’s At Home at the Zoo and its intimations of the Occupy movement, at Profile Theatre.

A few other things that’ve been keeping me hopping, each of which should be coming out in story form sometime soon:

- An evening up a dark alley to The Publication Studio for the opening celebration for artist Melody Owen‘s new book, which has something to do with mad hatters and rabbit holes.

- An afternoon at the Portland Opera studios, where I discovered general manager Christopher Mattaliano leaping up and down with a cutout version of a gingerbread witch as singers from Engelbert Humperdinck’s Hansel and Gretel watched and nodded.

- A morning at Milagro Theatre, talking with Dañel Malàn about the perils and pleasures of touring the country to perform bilingual plays in tucked-away spaces – and whether the world is really going to end with the Mayan calendar in 2012.

- An hour’s conversation on the phone with Hal Holbrook, octogenarian actor and uncanny channeler of the late, great Mark Twain, on topics ranging from politics to history to the unhappy state of print journalism and what it means to the future of democracy: “It’s a good paper. But as I remind people, it’s called the Wall. Street. Journal. Not The Journal. And it’s owned by that guy, Murdoch, who’s in all that trouble in England.”

Lots cooking, and more coming up. Last night I had an odd dream: I’d accepted an assignment from a glossy magazine to do a spread comparing two versions of barbecued pulled pork from famous Southern restaurants. This was a touchy situation for an ordinarily vegetarian/pescetarian writer, who was sorely tempted to do some serious taste-testing. In my dream I solved the problem by contacting the chefs of each restaurant and asking them to send me a towel soaked in their secret sauces. I then breathed in the aromas deeply, and began to type. If you should happen to stumble across this story somewhere in print, don’t believe a word it says.

*

ILLUSTRATIONS, from top:

- Photo by Keith Weller/Wikimedia Commons

- Hal Holbrook in 2007. Photo: Luke Ford, lukeford.net/Wikimedia Commons

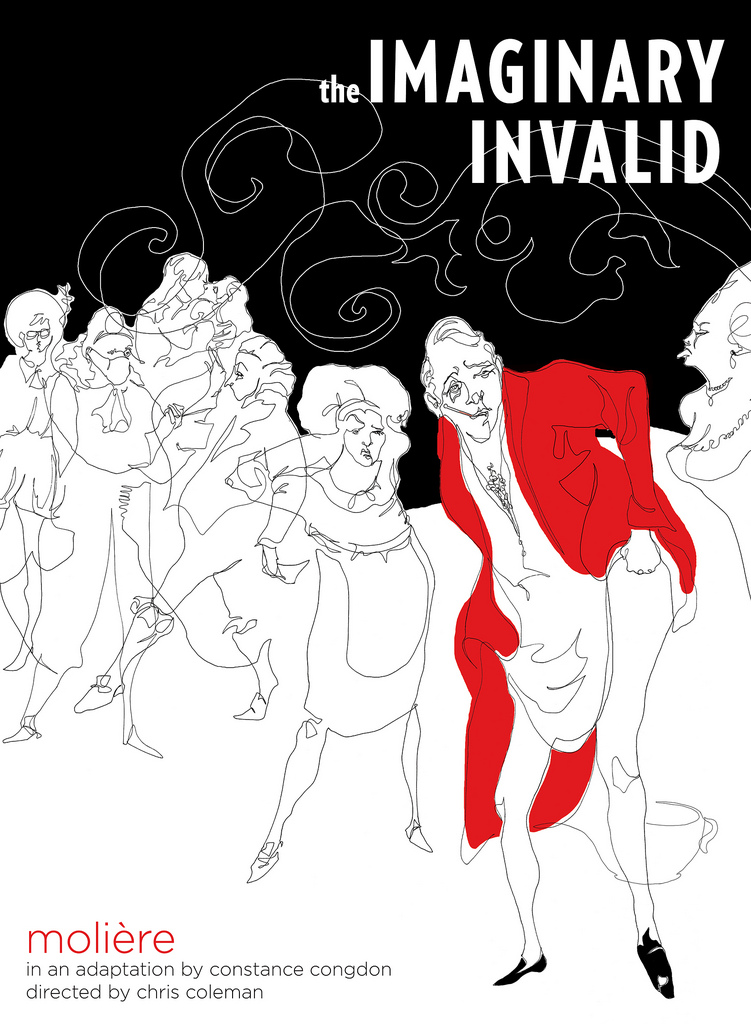

Pepys had notoriously little patience for Shakespeare and his fripperies. What might he have thought, then, of Constance Congdon’s adaptation of Moliere’s

Pepys had notoriously little patience for Shakespeare and his fripperies. What might he have thought, then, of Constance Congdon’s adaptation of Moliere’s

Besides being a homecoming of sorts — Blessing is a 1971 grad from Reed, where he directed and was directed by another high-profile theater alum,

Besides being a homecoming of sorts — Blessing is a 1971 grad from Reed, where he directed and was directed by another high-profile theater alum,