Nothing Sacred, the title of a 1937 Carole Lombard screwball comedy proclaimed, and Ben Hecht’s hilarious, hardboiled movie script pretty much summed up the American attitude on the subject: There is, indeed, nothing sacred — nothing not fit for examining, dissecting, debunking, putting on display for the amusement or edification of the curious public.

Why not turn cadavers into posed objects for museum display, as hugely popular shows such as Body Worlds do? They’re only mummified skin and bone. Any resemblance to any actual living human being who once inhabited this “plastinated” shape is purely on the surface, and inconsequential, anyway: It’s not as if the stiff is alive.

Why not turn cadavers into posed objects for museum display, as hugely popular shows such as Body Worlds do? They’re only mummified skin and bone. Any resemblance to any actual living human being who once inhabited this “plastinated” shape is purely on the surface, and inconsequential, anyway: It’s not as if the stiff is alive.

It’s all so rational. And, yes, there’s so much to legitimately poke fun at (Elmer Gantry and his heirs) or fear (suicide bombers stoked on righteousness). Faith, or its misconception, has made a mess of a lot.

And yet, much of the world simply doesn’t agree with modern rationalism and the intellectual assumption of superiority that so often accompanies it. And much of the world has a point. Do we keep getting into these foolish, messy wars partly because we find it hard to imagine that belief is important — that for some people, the sacred trumps self-interest? In snickering at the earnestness of evangelicals, does blue America simply mock something it hasn’t even tried to understand?

The question becomes fascinating when you extend it to indigenous cultures, where so often “sacred” and “secular” don’t really exist as opposite or even separate categories. It’s here, especially, where Western ideas of science and art run into troubles. Tenets that make perfect sense in the European tradition simply don’t apply. So we get a battle, for instance, over the remains of Kennewick Man.

In the museum world, repatriation is a hot, hot issue. It has to do with history, and the spoils of imperialism, and national pride, and the disputed rights of original ownership. Originating countries such as Greece, Italy and Egypt are firm in their demands that looted or casually sold artworks be returned (even if, sometimes, they simply land in the basements of already overstocked home-country museums). Art stolen by Nazis from Jewish collectors or sold on the cheap to finance escape from the Nazis is going off of museum walls and into the hands of the original collectors’ heirs. Now that Athens has a top-rate new museum at the Acropolis, repatriation advocates are arguing that the last remaining excuse for keeping the Elgin Marbles at the British Museum has crumbled away.

In the murky world of rightful ownership, repatriation isn’t always the clear-cut issue it seems at first glance. Issues of availability to a broad audience, of ability to display objects in a broader artistic context, and of the ability to keep objects in a safe environment and care for them adequately also are legitimate parts of the debate.

But what if the work in question isn’t even considered art in the eyes of its originating culture? That twists the argument in intriguing ways, and in one case this week, with a surprising result: The Seattle Art Museum has returned a sacred Aboriginal object to Australia — and SAM initiated the repatriation. Australia’s National Indigenous Times tells the story here, and Artdaily.org also reports.

You can’t see the object in the photo above, because the object isn’t meant to be seen by a general audience. SAM has had it in its collection since 1970, but it’s never put it on display. It’s being called a “secret/sacred object” that would be used by an Aboriginal man in religious ceremonies. And that means that, although from a Western viewpoint it might be an interesting anthropological and aesthetic object, from an Aboriginal viewpoint it’s off-limits to anyone but its owner/user.

In other words: It’s something sacred. And SAM — especially Pamela McClusky, the museum’s curator of African and Oceanic art — decided that that meant it doesn’t belong in an American museum. It belongs back where it began.

Regina Hackett, the former Seattle Post-Intelligencer art critic who now writes on her Art Journal blog Another Bouncing Ball, has a good insider’s take:

A student of Robert Farris Thompson‘s, McClusky is not your ordinary art curator. Like Thompson, she embraces the meaning first peoples give the objects that they create. She is far more likely to see the central Australian Aboriginal object in question as elders see it, rather than in purely aesthetic terms.

Once the object came to her attention, it was as good as gone.

“It’s something that is not to be seen by men who have not been initiated, by women or by children, and it’s intended to be kept in a relatively sacred, secret place, usually a cave,” ABC Canberra quotes McClusky.

The network further quotes her:

The museum has been displaying Australian Aboriginal art and a lot of Australians had been coming through and I would always say “do you want to come down to storage and see this material we have” and they would say “not a stone, that shouldn’t be here.”

Now, it’s not.

As Hackett reports, the object isn’t quite home yet, wherever “home” might be: “The National Museum of Australia will store the object temporarily while consultations proceed regarding its final repatriation.”

It’ll be fascinating to see where this object finally lands. Except that maybe it’s none of our business, and we just won’t find out. And maybe that’s alright.

Update: Walter Jaffe at White Bird Dance has passed along this note from Keith Goodman’s friend Carla Mann: “Dear friends, I wanted to let you know that a gathering to celebrate Keith Goodman will be held this coming Thursday, July 2 from 4-6pm at the Gerding Theater, 128 NW 11th. Please join family and friends in honoring this incredible man. Please also spread the word to others who knew Keith and who we may not be on our contact list. For those who are interested, contributions can be made to the Keith V. Goodman Memorial Fund through the On Point Credit Union.”

Update: Walter Jaffe at White Bird Dance has passed along this note from Keith Goodman’s friend Carla Mann: “Dear friends, I wanted to let you know that a gathering to celebrate Keith Goodman will be held this coming Thursday, July 2 from 4-6pm at the Gerding Theater, 128 NW 11th. Please join family and friends in honoring this incredible man. Please also spread the word to others who knew Keith and who we may not be on our contact list. For those who are interested, contributions can be made to the Keith V. Goodman Memorial Fund through the On Point Credit Union.” By MARTHA ULLMAN WEST

By MARTHA ULLMAN WEST

Here’s the thing. Arts people have been around a very long time, and no matter how hard you kick ’em around, they keep popping back up.

Here’s the thing. Arts people have been around a very long time, and no matter how hard you kick ’em around, they keep popping back up. Sojourn is a Portland-based company that tours the country, developing and performing community-based plays that usually coalesce around specific themes. For the last year, among a myriad of other activities, it’s been working on a new piece called On the Table that looks at food, and how it’s grown and distributed, and the choices we make about it, and the impact it has on various communities. A lot of field reporting (in this case, literally) goes into a typical Sojourn show, and that takes time and resources. Company director Michael Rohd figures the project has another year to go: “The show will happen Summer 2010 simultaneously in PDX and a small town 50 miles from PDX, and explores the urban/rural conversation in Oregon, culminating with a bus trip for both audiences and a final act at an in-between site,” he says.

Sojourn is a Portland-based company that tours the country, developing and performing community-based plays that usually coalesce around specific themes. For the last year, among a myriad of other activities, it’s been working on a new piece called On the Table that looks at food, and how it’s grown and distributed, and the choices we make about it, and the impact it has on various communities. A lot of field reporting (in this case, literally) goes into a typical Sojourn show, and that takes time and resources. Company director Michael Rohd figures the project has another year to go: “The show will happen Summer 2010 simultaneously in PDX and a small town 50 miles from PDX, and explores the urban/rural conversation in Oregon, culminating with a bus trip for both audiences and a final act at an in-between site,” he says.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8.

Of course, I’d just driven the 110 miles east from Portland to see a bunch of paintings by dead people: the museum’s show Hudson River School Sojourn, which is on view through July 8. But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

But as crucial as those things are to Maryhill’s identity (a prominent art historian told me the other day that the museum should concentrate on its “creation myth”), they’re not the whole story. Musgrave, a practicing contemporary painter who’s been showing his own work since the late 1960s in California, the Northwest, and even Australia and Japan, has nurtured relationships with contemporary-art collectors such as Portland’s Jordan Schnitzer. He’s worked directly with a lot of artists, and he’s nurtured at least a nascent sense that in this place, time can mingle. “My favorite thing to do is to take contemporary artists and combine them with things in the permanent collection,” he says.

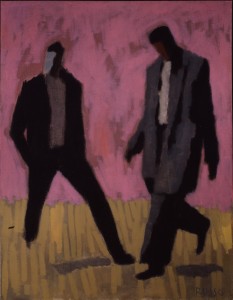

The show began with TouchMonkey, in the persons of Carolyn Stuart and Patrick Gracewood, who are longtime practitioners of Contact Improvisation, a form based on trust and the ability to make on-the-spot kinetic connections. Stuart was wearing a black cloth over her eyes, which meant her responses to Gracewood were entirely by touch and contact. Their duet, titled Special Alembics, (nice pun!) was performed to music played live by Eddy Deane, Alley Teach, and David Lyles of The Contact Lounge Band.

The show began with TouchMonkey, in the persons of Carolyn Stuart and Patrick Gracewood, who are longtime practitioners of Contact Improvisation, a form based on trust and the ability to make on-the-spot kinetic connections. Stuart was wearing a black cloth over her eyes, which meant her responses to Gracewood were entirely by touch and contact. Their duet, titled Special Alembics, (nice pun!) was performed to music played live by Eddy Deane, Alley Teach, and David Lyles of The Contact Lounge Band.

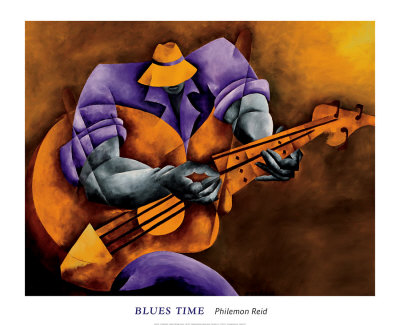

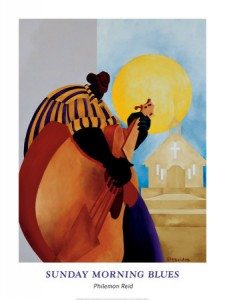

And through it all he did the thing he loved to do, which was to paint and sculpt images of the African American musicians who played the blues and jazz. He often listened to Coltrane or Miles or Ella while he was making his own art.

And through it all he did the thing he loved to do, which was to paint and sculpt images of the African American musicians who played the blues and jazz. He often listened to Coltrane or Miles or Ella while he was making his own art. While Art Scatter was spending Thursday in the Columbia Gorge visiting the

While Art Scatter was spending Thursday in the Columbia Gorge visiting the  PNCA at 100: Two good pieces on the

PNCA at 100: Two good pieces on the Mr. Salinger does know the legal profession, and in pursuit of his vaunted rights has made liberal use of it over the years. The New York Times reports

Mr. Salinger does know the legal profession, and in pursuit of his vaunted rights has made liberal use of it over the years. The New York Times reports