My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind.

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind.

We’ve had our share of bad news on the cultural front, too. A ballet company on the brink. A symphonic orchestra making deep budget cuts. A contemporary dance center in dire straits. All sorts of arts groups wondering, with good cause, whether they’ll make it through these tough times.

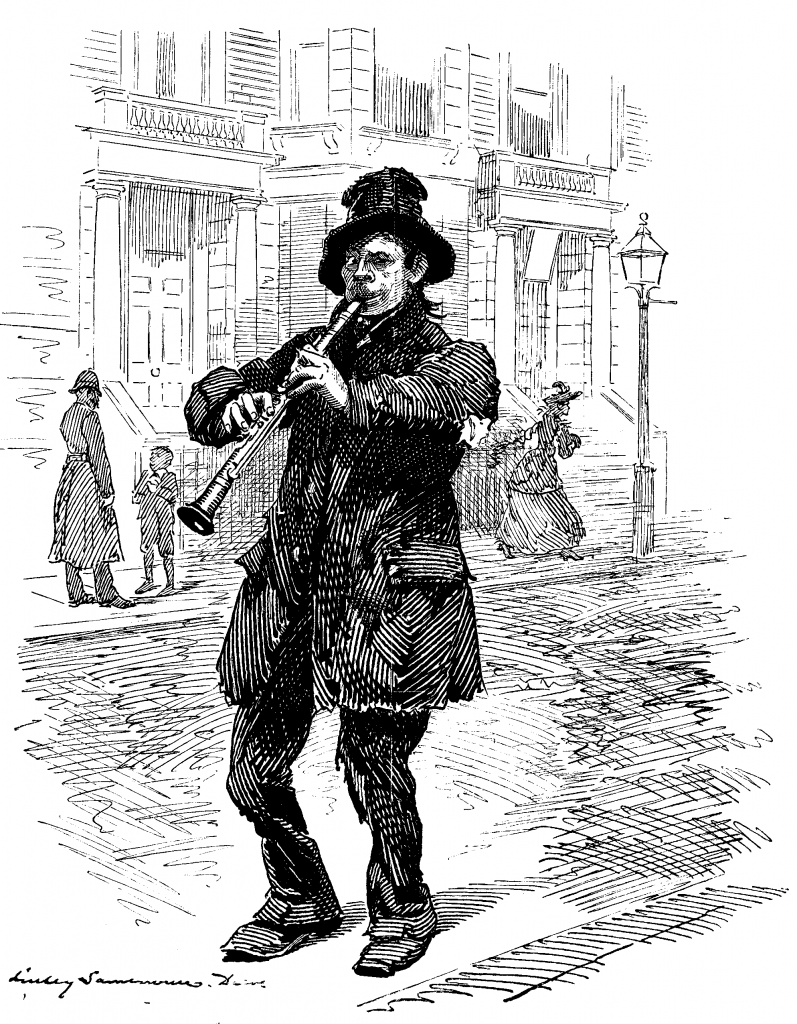

But the deal is, this town’s crawling with culture. It might not always be “high” culture and it might not always be buffered by wealthy patrons, but it’s all over the place, fed by the enthusiasms of people who create a scene around something because they genuinely enjoy what it is and the impact it has on their lives. Depression or not, you can’t keep curiosity from putting on its walking shoes and going out for a stroll.

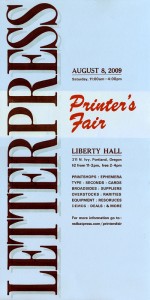

Today I went to the minor mob scene that was the Letterpress Printers’ Fair at Liberty Hall, a small, well-weathered space stuck to a stubborn outcropping of North Ivy Street that refuses to give up its character to the waves of noise and hurtling traffic from the nearby freeway exchange that slashes through the neighborhood like a tornado through a Kansas farm. Liberty Hall clings to life and the public welfare like a robust, exotically flowering weed whose beauty is in the eye of chosen beholders. It’s a gritty joint, and I mean that in a good way.

Ivy turns into almost an alley at Liberty Hall, and today pedestrians took precedence over drivers. Printing enthusiasts were spilling out on the street. Vendors in the little front yard were cranking out sandwiches, selling carroty-looking cookies and cakes, dispensing drinks. The front porch was jumping, and once you got through the door it was like squeezing into the current with a school of fish. Rows of tables, a make-your-own print setup on the stage, printed T-shirts for sale and booth after booth offering greeting cards, posters, broadsides, hand-stitched books, pieces of old printers’ type, stationery and the varied wares of varied small presses.

In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose 23 Sandy Gallery specializes in photography and book arts; in October her gallery will feature Broadsided! The Intersection of Art and Literature, a national juried exhibition of letterpress-printed broadsides.

In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose 23 Sandy Gallery specializes in photography and book arts; in October her gallery will feature Broadsided! The Intersection of Art and Literature, a national juried exhibition of letterpress-printed broadsides.

“Crowded,” I said, squeezing into speaking range.

“This is quiet compared to this morning,” she shouted. “It was really packed then!”

So what excites all this passion? I think it has something to do with this city’s love for the small-scale, the handmade, the forgotten and outmoded, the aged but still lovely. With holding and feeling and handling things. With craft and artisanship. With making something on your own and saying, “That’s good!”

Printing is a tactile affair. It holds the advantage that a book holds over this digitized thing we’re writing and reading right now. It makes an impression, literally: little hills and valleys on the page, with the elegance and imperfections of the process. The paper, the imprint, the design, the stitching, the inking, all conspire to create something physical that offers the illusion if not the actuality of permanence. A letterpress creates a thing — a thing that can be beautiful, at a cost that most people can afford.

Like baseball, it holds its own history and its own language. The tray with the little cubicles that hold the print is the job case. The bits of blank metal that create spaces are called leading. You use coppers and brasses and kerns and ems and ens, and when you’ve finally got everything ready to roll you got that satisfying thwack! thwack! thwack!

Like haiku, a letterpress has severe limitations but opens a world of imagination. I saw some lovely bookmaking at the Oregon College of Art & Craft booth, and nice broadsides, and a series of fascinating monster cards — Dracula, King Kong, Frankenstein’s creature, with pertinent textual quotes for each — that caught my eye as a possible gift for my daughter, who knows her gothic although she is not arch.

“How much are these?” I asked.

“Oh, they’re not for sale,” a young woman replied. “These are just samples of students’ work that we’re showing.”

I liked learning about places with arcane names that stake their claim to their own oddball eddy in the stream. Letterary Press. Obscura Press. Cupcake Press. Twin Ravens Design & Letterpress. Red Bat Press. Stinky Ink Press (now there’s truth in advertising). Tiger Food Press. Emspace Book Arts Center. Bartleby’s Letterpress Emporium. Stumptown Printers Worker Cooperative, which promises “simple & sexy printing and paper-based products.”

So let the presses roll. Have fun. Surprise yourselves. Make beautiful things. Take sweet revenge on the economy. And try to keep your apostrophes under control.

“No kissing of ring necessary,” his partner, Sherry Lamoreaux, insists. But we can scarce restrain ourselves.

“No kissing of ring necessary,” his partner, Sherry Lamoreaux, insists. But we can scarce restrain ourselves. It’s 30 minutes long, and

It’s 30 minutes long, and

The intrepid Mighty Toy Cannon has the story at Culture Shock;

The intrepid Mighty Toy Cannon has the story at Culture Shock;

And I watch chick flicks. Not just any chick flick, but the well-written, well-performed ones that tend to fall into the folds of screwball or romantic comedy. Yes, I like the movies of Nora Ephron, and if that drums me out of the league of tough-guy arts observers, so be it.

And I watch chick flicks. Not just any chick flick, but the well-written, well-performed ones that tend to fall into the folds of screwball or romantic comedy. Yes, I like the movies of Nora Ephron, and if that drums me out of the league of tough-guy arts observers, so be it. The best chick flicks exude optimism, which of course makes them immediately suspect in intellectual circles. (Then again, a lot of intellectuals miss the point that Waiting for Godot is as much a vaudeville comedy as it is an existential outcry: Even Beckett enjoyed a good giggle.)

The best chick flicks exude optimism, which of course makes them immediately suspect in intellectual circles. (Then again, a lot of intellectuals miss the point that Waiting for Godot is as much a vaudeville comedy as it is an existential outcry: Even Beckett enjoyed a good giggle.) It’s a coupling of equals built on compromise and respect, and it typically involves wriggling out of a bad potential match and shedding several layers of self-delusion so you can see the simple beauty of what ought to be. That often requires eating a few slices of humble pie and taking some practical steps. In that sense, Jane Austen is the mother of all chick flicks. And Shakespeare, with his comic creations of Kate and Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew and Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, might be their grandpa.

It’s a coupling of equals built on compromise and respect, and it typically involves wriggling out of a bad potential match and shedding several layers of self-delusion so you can see the simple beauty of what ought to be. That often requires eating a few slices of humble pie and taking some practical steps. In that sense, Jane Austen is the mother of all chick flicks. And Shakespeare, with his comic creations of Kate and Petruchio in The Taming of the Shrew and Beatrice and Benedick in Much Ado About Nothing, might be their grandpa.

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind.

My front page this morning was nothing but economic trouble: condo sales in collapse, another bank failure, Congress squabbling over the price of health care reform, an analysis of the cash-for-clunkers program (it’s good for car companies, not so much of an environmental boon) and, tucked into one corner, the curious declaration by a group of economists that things are looking up. These were employed economists; unemployed economists tend to be more aware of the emperor’s bare behind. In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose

In one corner I ran into Laura Russell, whose

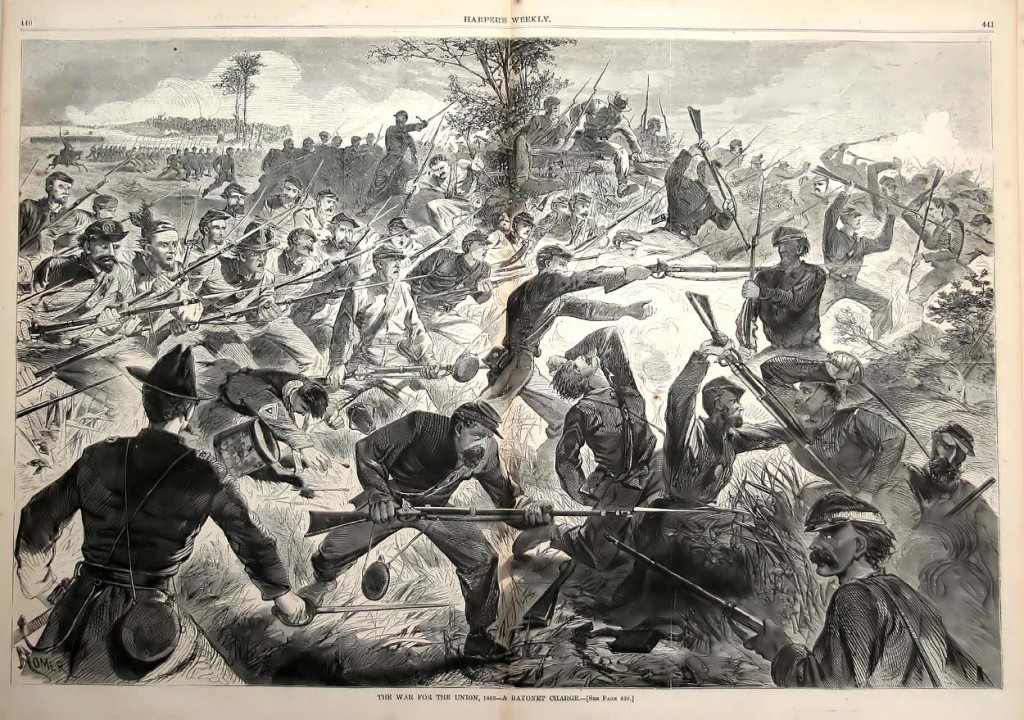

Nobody seems to remember anymore what the fabled bull and bear stand for, the story comments, and they got that right: If investors and manipulators hadn’t conveniently forgot that the bull periodically and inevitably transforms into a bear, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now. Optimism is a lovely thing, but not when it doesn’t have its feet on the ground.

Nobody seems to remember anymore what the fabled bull and bear stand for, the story comments, and they got that right: If investors and manipulators hadn’t conveniently forgot that the bull periodically and inevitably transforms into a bear, we wouldn’t be in the mess we’re in now. Optimism is a lovely thing, but not when it doesn’t have its feet on the ground. Readers of Laura Grimes’ recent post

Readers of Laura Grimes’ recent post