What happens when you invite a rough-and-tumble whiskey guy to the vicar’s garden tea party? We’re about to find out. Last week President Obama nominated Rocco Landesman to be the next chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts, and suddenly crumpets beneath the arbor seem a little tame.

Landesman, who owns and runs Jujamcyn Theaters on Broadway, is no not-for-profit guy. He takes chances and he makes money (and sometimes he loses it). He likes baseball, country music and horse racing, and he’s never been much for touchy-feely collaboration: He likes to run the show.

Landesman, who owns and runs Jujamcyn Theaters on Broadway, is no not-for-profit guy. He takes chances and he makes money (and sometimes he loses it). He likes baseball, country music and horse racing, and he’s never been much for touchy-feely collaboration: He likes to run the show.

This is a guy, it seems, who’d as soon smash the not-for-profit cup as paint it with pretty posies.

So why are so many arts types beaming at the possibilities? “Rocco is no diplomat, but he’d blow the dust off a moribund organization that has contented itself in recent years with a policy equivalent of art appreciation,” Portland theater guy Mead Hunter writes approvingly on Bloghorrea. Christopher Knight at the L.A. Times’ Culture Monster says the whole thing startled him because he’d almost forgotten there was an NEA.

And a friend in New York arts circles is ecstatic, even if Landesman turns out to be a short-termer. “A lot of the time the guy who kicks a hole in the wall is not the same guy who goes through the wall,” she says. Of course, she adds, kicking a hole is no guarantee. The next person can either walk to the other side, or patch the wall and return to life as usual.

Certainly Landesman’s record as a theater leader — and increasingly, as an industry spokesman — is strong. Jujamcyn has five shows on Broadway right now, including “Hair,” “33 Variations” and “Desire Under the Elms,” and Landesman’s had a hand in shows as important as “Angels in America,” “Spring Awakening,” “The Producers,” “Grey Gardens,” the great August Wilson’s Broadway productions, the revivals of “Gypsy” and “Sweeney Todd,” “Big River” and “Doubt.”

He raised both hackles and hopes when he accused the not-for-profit theater world of acting too much like the commercial theater. It was an elephant-in-the-living-room comment, and not calculated to keep things warm and fuzzy. Is it true? In what ways? What’s the difference between for-profit and not-for-profit in the cultural world? I have my views. It’d be fascinating to hear yours. Hit that comment button and let’s start a conversation.

*********************************************************

The National Endowment for the Arts is a federal bureaucracy, and that makes its chairmanship an intensely political position. What began in a burst of optimism in 1965 as a part of the Great Society — Lyndon Johnson’s push to expand the economic and cultural advantages of the urban East to all corners of the country — devolved by the 1980s into an unwilling infantry skirmish in the nation’s cynical “culture wars.” The NEA, a truly democratic bureaucracy, was targeted by right-wing radical warriors as a breeding ground of unAmericanism, and its survival was thrown in doubt, although enemies such as Sen. Jesse Helms and polemicist Pat Buchanan needed it as a whipping boy.

Oregon lawyer John Frohnmayer, appointed NEA boss by the first President Bush, quickly learned it was all about politics. Pressured from the right and challenged from the left, he tried to parse the difference and ended up pleasing no one, especially after fumbling the divisive “NEA Four” case in 1990. The upshot: The NEA was weakened further, Frohnmayer lost his job, and he was born again as a First Amendment crusader. Free speech, he learned, doesn’t come free.

In the new storyline Dana Gioia, George W. Bush’s NEA chief, is the nice boring guy who threw the tea party that Landesman’s about to smash up. And there’s no doubt, the NEA has been far more timid than most people in the arts world would like it to be.

But different times call for different politics, and Gioia was stuck with the time he got. The man was no dummy. Yes, he was a soothe-the-ruffled-feathers guy. Yes, he emphasized things like folk arts and tended to bestow honors on the obvious sort of people who get hauled out to perform on public television pledge week. Yes, he oversold the tried-and-true and ducked the controversial.

But he also saved the endowment’s skin. After years of shrinking budgets and Congressional threats to kill the agency off, he steered the NEA away from the culture wars and succeeded in getting some modest boosts in its budget. He emphasized spreading the money around to small-population states and rural areas as well as the country’s cultural capitals, and he finally succeeded in persuading most of Congress that the arts are a good thing, even if he had to slap a smiley face on the product to push the sale through.

One thing sticks in my memory. Oregon was going through yet another of its periodic budget crises a few years ago and the state Legislature, looking for ways to cut costs, was floating the idea of killing the already slimly financed Oregon Arts Commission, which among other things funnels money from the NEA to recipients in the state.

I called Gioia and asked him what he thought of it. Well, gee, he replied, the problem is, we have this federal money to give out, and if there’s no state agency to give it to, we can’t legally give any of it to anyone in Oregon. Oregon’s share would have to go to other states. And that would be too bad. But of course, legally, our hands would be tied.

Nice, quick, apologetic, to the point — and very effective. That’s politics.

If Landesman shakes things up, it’ll be because the time has come to do some shaking. That’s politics, too.

Locally, arts marketing whiz Trisha Mead sounded the alarm (she was even quoted in the New York Times) and Art Scatter’s brother in arms, Barry Johnson, has been carrying the conversation forward with several posts at Arts Dispatch. Mr. Scatter has even sprinkled a couple of comments into his threads.

Locally, arts marketing whiz Trisha Mead sounded the alarm (she was even quoted in the New York Times) and Art Scatter’s brother in arms, Barry Johnson, has been carrying the conversation forward with several posts at Arts Dispatch. Mr. Scatter has even sprinkled a couple of comments into his threads.

Impossible to even think about that now, which must mean Portland’s evolving into a city at last.

Impossible to even think about that now, which must mean Portland’s evolving into a city at last. Another big player in those midcentury years, sculptor and printmaker Manuel Izquierdo, died in July. Notable (like so many of his contemporaries) as a teacher as well as an artist, he was also one of the artists who connected the Northwest’s sometimes insular scene to international ideas. He was born in Madrid, left Spain during the Civil War, and spent most of his adult life in Portland. But he brought a European spirit with him.

Another big player in those midcentury years, sculptor and printmaker Manuel Izquierdo, died in July. Notable (like so many of his contemporaries) as a teacher as well as an artist, he was also one of the artists who connected the Northwest’s sometimes insular scene to international ideas. He was born in Madrid, left Spain during the Civil War, and spent most of his adult life in Portland. But he brought a European spirit with him. Hoving was a swashbuckler, a showman, a democratizer, maybe even something of a pirate. When he took over the great Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan in 1967, at the age of 35, he declared it moribund and set out to make it the most popular show in town.

Hoving was a swashbuckler, a showman, a democratizer, maybe even something of a pirate. When he took over the great Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan in 1967, at the age of 35, he declared it moribund and set out to make it the most popular show in town.

*************************

************************* Landesman, who owns and runs

Landesman, who owns and runs

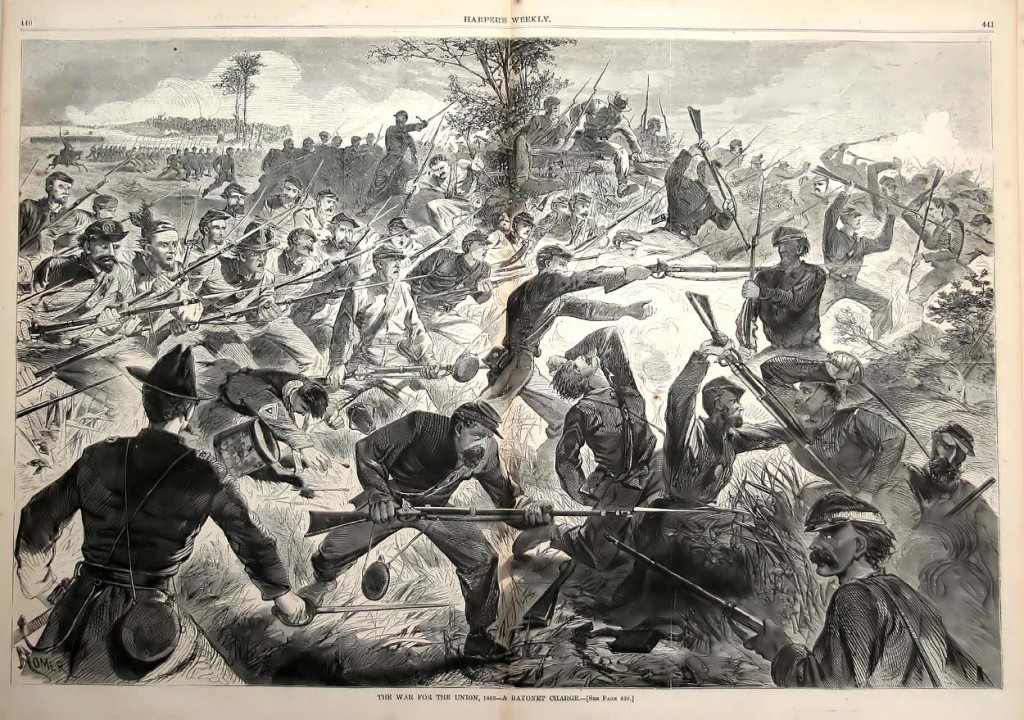

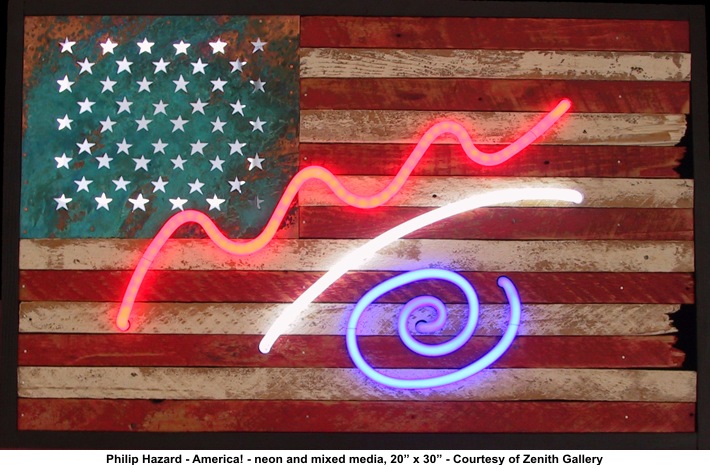

So much for bipartisanship. All of a sudden it feels like we’re back in the bad old days of the 1980s and ’90s “culture wars,” when the right-wing juggernaut raised fears of

So much for bipartisanship. All of a sudden it feels like we’re back in the bad old days of the 1980s and ’90s “culture wars,” when the right-wing juggernaut raised fears of