“Do it in German,” Beth Harper said.

Harper, the guiding light of Portland Actors Conservatory, was talking with Simona Constantin, who after two years at the conservatory was trying to figure out what she should do for this week’s graduation showcase Wednesday through Saturday nights.

Constantin, whose English is way better than your German probably is, was worried that her English skills were too rough. And, as much as she loves Portland, she was getting ready to return home to Berlin at the end of summer, where she’ll try to break in to the professional theater scene.

So, do it in German.

She will. Constantin, one of nine grads who’ll perform monologues in this week’s program, will perform one piece in English (Christina Mulchauy’s Sex in a Cold Climate) and one in German: Die Heirat, or The Marriage, by Nicolai Gogol. And if that doesn’t prove that acting’s an international language, nothing will: a German actress from an American school performing a Russian play in a German translation for an American audience.

“The goal is, after two years, to turn out actors who are ready to go out and act in the professional world,” Harper said a couple of weeks ago at a small media gathering to showcase the showcase and the conservatory itself.

“The goal is, after two years, to turn out actors who are ready to go out and act in the professional world,” Harper said a couple of weeks ago at a small media gathering to showcase the showcase and the conservatory itself.

And if your professional world is going to be in Berlin, … well, there you go. Beth Harper is a very practical dreamer, and her advice to Constantin was vintage Harper: Think big, go for it, but figure out how to get there.

It’s been a long road for Portland Actors Conservatory, which is celebrating its 25th anniversary, and I’m happy to say I was there when it was on the ground floor.

Which it wasn’t. It was a walkup in the Hollywood District, in a couple of rooms that had been a dentist’s office, and its ribbon-cutting was jammed with prominent theater folk of the time: I remember talking with Isabella Chappell and Bill Dobson from the old Portland Civic Theatre. Later, when it was still called The Training Ground, the conservatory moved to another walkup in Old Town with a cramped little theater whimsically called the Loft in Space. Finally it landed at the Firehouse Theatre, a city-owned former firehouse just above downtown on a hill to the west of Portland State University, and there it remains, busting at the seams. (There are remodeling plans to make the place play bigger.)

In the early years of my accidental career as a theater critic, Beth was one of the people who helped me realize that theater is the stuff that happens in the spaces between the actors: the energy, the connections, the passing of the ball on the fast break. She was a very fine actress, and a very good director, the kind who never let herself show but brought the best out of the script and the performers. She studied those scripts, broke them down, then put ’em back together again. And she talked a lot about the need for craft to let the art come out.

So it wasn’t a huge surprise when she became a teacher and a businesswoman. And an idea of making this thing a true school was always part of the dream. Last year the conservatory gained full accreditation from the National Association of Schools of Theatre, a major step but far from the end of Harper’s grand plan.

Now, for a select group (as many as 20 students the first year, down to 12 max the second) the conservatory offers its two-year, full-time professional program. It continues its studio program for ongoing studies — a necessity in a discipline like theater — a summer youth program and a season of plays performed by students and guest actors.

It’s also a hallmark of Harper’s practical approach to theater that the conservatory offers a variety of approaches to the craft. Students learn movement, clown, Meisner Technique, Shakespeare, improv, text analysis. They learn design, and even theater management. Whatever works. Whatever technique gets you there. That’s the one to use.

Teachers include the likes of Michael Mendelson, Sarah Lucht, Philip Cuomo, Rose Riordan and Cynthia Fuhrman — names to be reckoned with around here. Grads include the likes of Maureen Porter, Rafael Untalan, Andrea Alton (Saturday Night Live), Brooke Blanchard (The West Wing), Mario Calcagno, Gilberto Martin del Campo, Zero Feeney and Nathan Gale.

What’s it all come down to?

“After two years,” the graduating Constantin says, “you are more of yourself than you were when you came here.”

Not a bad result.

—————————————————–

DETAILS on this week’s conservatory graduation showcase:

WHO: 2009 graduating class of Portland Actors Conservatory

WHAT: Graduation Showcase performance, An Evening of Monologues

WHEN: 7:30 pm Wednesday through Saturday, July 15-18

WHERE: Portland Actors Conservatory

1436 SW Montgomery Street

Portland, OR 97201

COST: $15

TICKETS: http://www.actorsconservatory.com

Call 503-274-1717 for the box office

Photos by Drew Foster

About visual art, definitely. We’ve created a mumbo-jumbo priesthood of commentary and pretend the intellectual abstraction is more important than the physical experience of the art itself. Which it is, but only sometimes. And far less often than the priesthood likes to think.

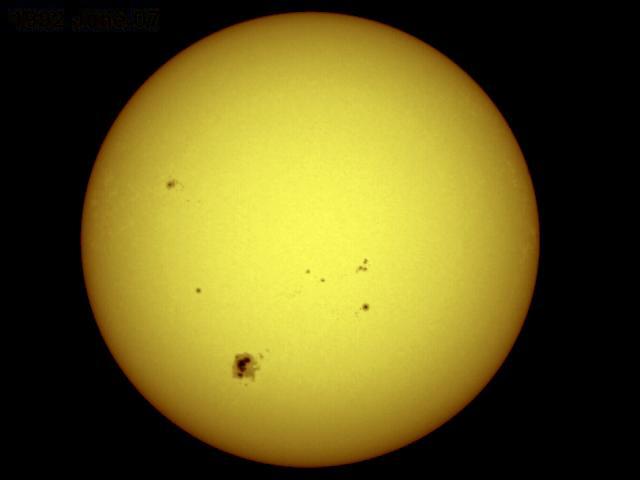

About visual art, definitely. We’ve created a mumbo-jumbo priesthood of commentary and pretend the intellectual abstraction is more important than the physical experience of the art itself. Which it is, but only sometimes. And far less often than the priesthood likes to think. Today, in the throes of an infernal Pacific Northwest heat wave that has the thermometer rattling up toward 107, that red-baked head is on my mind again. Kind of blue, kind of hot, an oddly triumphal moan, mixed of resignation and endurance and somehow coming out on the sweet side of things: I ain‘t dead.

Today, in the throes of an infernal Pacific Northwest heat wave that has the thermometer rattling up toward 107, that red-baked head is on my mind again. Kind of blue, kind of hot, an oddly triumphal moan, mixed of resignation and endurance and somehow coming out on the sweet side of things: I ain‘t dead.

Joe Meek, maybe. Jedediah Smith. Liver-Eating Johnson. Jim Bridger.

Joe Meek, maybe. Jedediah Smith. Liver-Eating Johnson. Jim Bridger. Niel DePonte has another idea, and you can read about it on this morning’s Oregonian editorial page, under the headline

Niel DePonte has another idea, and you can read about it on this morning’s Oregonian editorial page, under the headline  No computer screens today, though. On most Sunday mornings Destino offers a bonus: Guitarist John Dodge sits on a stool in the corner by the kids’ toys, small amp propped on a chair beside him, and gives the French blend and bagels a musical setting. It’s melodic, and just the right decibel, and a bit Robert Browning-ish in its simple elegance: All’s right with the world.

No computer screens today, though. On most Sunday mornings Destino offers a bonus: Guitarist John Dodge sits on a stool in the corner by the kids’ toys, small amp propped on a chair beside him, and gives the French blend and bagels a musical setting. It’s melodic, and just the right decibel, and a bit Robert Browning-ish in its simple elegance: All’s right with the world.

“The goal is, after two years, to turn out actors who are ready to go out and act in the professional world,” Harper said a couple of weeks ago at a small media gathering to showcase the showcase and the conservatory itself.

“The goal is, after two years, to turn out actors who are ready to go out and act in the professional world,” Harper said a couple of weeks ago at a small media gathering to showcase the showcase and the conservatory itself.

Today is the 150th anniversary of Big Ben’s first chime, and

Today is the 150th anniversary of Big Ben’s first chime, and