Remember the old days, when Cadillac-sized opera singers planted their feet among the scenery and belted beautiful music with no thought to the dramatic possibilities of the opera? Art Scatter’s senior correspondent Martha Ullman West does, and she shudders at the memory. What’s more, she sees the old style’s residual effects in the staging of “Orphee” at Portland Opera. Her message: Pay attention to the dancemakers. They have lessons for the musical stage.

Philip Cutlip as Orphee and Lisa Saffer as La Princesse. photo: Cory Weaver/Portland Opera

First the disclaimer — my opera expertise is limited, although my opera attendance began when I was 10 when my father took me to a New York City Opera production of The Marriage of Figaro. I really got the bug when I was in college, and for the past 35 years or so I’ve been an off and on subscriber to the Portland Opera.

So I belong to a generation of opera-goers that has seen a paradigmatic shift in staging: Gone, mostly, are the days when Licia Albanese, say, as the tragic Butterfly, planted her feet, opened her mouth and sang (in heavenly fashion, I might add) her concluding aria; or Pavarotti, as the lascivious duke in Rigoletto, did the same. Today, opera singers have to be able to move. Body language is part of the art form.

And in a Philip Glass opera, they ought to be able to move a lot more dynamically than they were directed to do in Orphee, which I saw Sunday afternoon. In all other respects I thought Portland Opera’s production was stunning, from the score, to the conducting, to the set, to the singing, particularly by Philip Cutlip as Orphee, Georgia Jarman as Eurydice and Lisa Saffer as the Princess.

BUT, my esteemed colleague David Stabler complained in The Oregonian that the production was static, and he’s right. Only Cutlip and Jarman seemed really physically at ease onstage, moving naturally, and with a certain amount of impulse. Saffer did indeed prowl from time to time, but that’s all she did, except to smoke, and everyone else moved stiffly and self-consciously, when they moved at all, except for a bit of leaping on and off of sofas and the bar in the party scene.

I couldn’t help thinking how different it would have looked if it had been directed by Jerry Mouawad in the way he staged No Exit for Imago. In fact, speaking of French poets, are we in Portland this fall enjoying a Season in Hell? (That’s Rimbaud’s long poem, and come to think of it, it would make a dandy opera.)

Glass deserves better physical direction for his operas. He has collaborated with a lot of choreographers. In fact, the first review I did for Dance Magazine, in 1979 (an essay review on post-modern dance in New York) included the premiere of DANCE, a piece he did with Lucinda Childs, which included elegant film images and for which he performed accompaniment himself.

Continue reading A dance critic at the opera: Move it, singers!

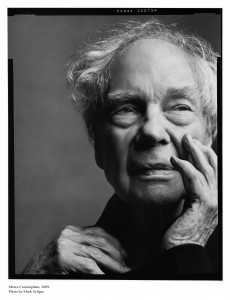

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche.

Merce Cunningham died the other day, in his sleep it is said, which means he was still hard at work at the age of 90. Artists do, you know, work in their sleep, as well as their waking hours. There is no rest for the psyche. About visual art, definitely. We’ve created a mumbo-jumbo priesthood of commentary and pretend the intellectual abstraction is more important than the physical experience of the art itself. Which it is, but only sometimes. And far less often than the priesthood likes to think.

About visual art, definitely. We’ve created a mumbo-jumbo priesthood of commentary and pretend the intellectual abstraction is more important than the physical experience of the art itself. Which it is, but only sometimes. And far less often than the priesthood likes to think.